Photo: Hunter Davis

“I vowed never to go back to that mountain,” Peter Barr says, describing his trek up Sugarland Mountain, the toughest hill he had to summit while trying to bag every peak above 5,000 feet in the Southeast. “There was a dark moment when I was experiencing the first stages of hypothermic and I made some bad judgments and went down the wrong side of the mountain. I thought it was going to be a 20 minute off-trail hike to the summit, but it turned into a four-hour ordeal. It started snowing. I got superficial frostbite on my hands. I didn’t get the feeling back in my fingers until three weeks later.”

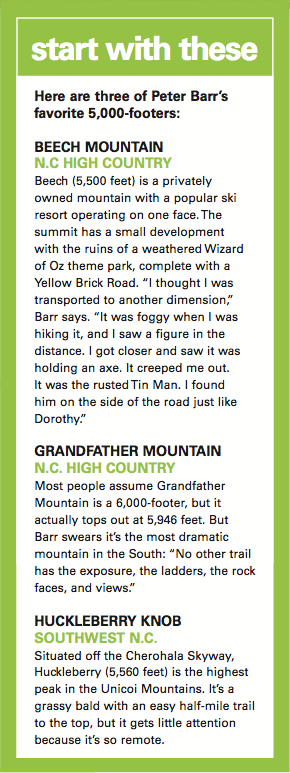

There are 135 different mountains that are above 5,000 feet in the Southeast, mostly along North Carolina’s western border. There are three in Virginia, one in Tennessee. Barr, an outreach coordinator for the Carolina Land Conservancy, is only the second person to climb them all. He’s one of the most accomplished hikers in the South, with an Appalachian Trail thru-hike under his belt, all 900 miles of Great Smoky Mountains National Park completed, and a South Beyond 6000 badge to his name (climbing all 40 peaks above 6,000 feet in the South). But Barr says the 5,000-foot challenge was the toughest of his bipedal accomplishments.

“Sugarland was the worst, but overall, they were monumentally tougher than climbing the 6,000-foot mountains,” Barr says. “You’d think that the lower the peak, the less extreme the mountain, but it’s usually the opposite. Six-thousand-foot peaks are more popular, so they typically have trails and man-ways to

the top.”

Most 5,000-foot peaks, on the other hand, aren’t on hikers’ radars, so trails are scarce, and beta is even tougher to find.

Most 5,000-foot peaks, on the other hand, aren’t on hikers’ radars, so trails are scarce, and beta is even tougher to find.

“I swam in more rhododendron than I cared to,” Barr says. “And I spent tons of time on Google Earth looking for the best way to the top of various mountains. Power line cuts, old roads that aren’t on maps…anything that would get me to the top of the peak without having to bushwhack.”

While the South’s jungle-like rhododendron adds charm to the 5,000-foot peak challenge, the real barrier is “No Trespassing” signs. Many of the highest mountains in the South have been protected as public property, but a significant portion of the 135 mountains over 5,000 feet are still on private property. Barr spent a lot of energy tracking down the current owners of several peaks and asking for permission to hike in their backyard. Surprisingly, all of the landowners he contacted acquiesced.

“Some people I had to ask twice and really explain myself, but eventually, everyone understood what I was trying to do,” Barr says. Peak bagging isn’t an easy thing for a lot of people to understand. While it’s hugely popular in the Northeast, where mountain climbing challenges like the New Hampshire 4000-Footer Club has seen thousands of finishers, the South’s most popular hiking challenge, the South Beyond 6000, only has 150 finishers. And it’s 40 years old. The notion of climbing a mountain just because it has a certain elevation hasn’t caught on in the Southern Appalachians yet, but Barr, who helps manage the SB6K challenge, sees it gaining traction.

“There are only a few people slowly ticking off the 5,000-footers right now, but every year we see 10 people complete the SB6K,” Barr says. “People are beginning to realize there’s more to peak bagging than just completing a challenge. It takes you to so many places you’d normally never go.”

The Rules

There are surprisingly few rules governing peak bagging challenges like the South’s 5,000 Peak Challenge. For instance, there’s no rule about the distance you have to hike to reach the top. You can even drive to the summit if it’s an option.

“As long as I get to the top without the help of a helicopter, I count it,” Barr says. “There are a few you can drive to, but I’ll take the occasional easy peak because so many of them are so tough.”

But not every peak in the South is considered a mountain. In order to be a peak worth bagging, there needs to be at least 300 feet of prominence, meaning the summit has to rise 300 feet above the low point of its connecting ridge.“ Just because a knob is named,” Barr says, “doesn’t make it a mountain.”