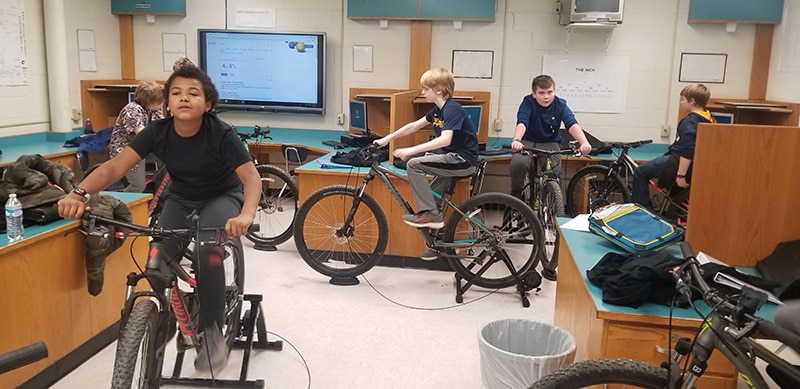

The South Middle School Mountain Biking Club is the oldest and largest of its kind in West Virginia. Photo by Evan Fedorko (@erghjunk)

How a middle school club in West Virginia started a statewide movement to help kids access the mental health benefits of mountain biking.

Having once freelanced as a local sports reporter, I’m familiar with afterschool athletic scenes centered around football, softball, soccer, lacrosse, you name it. But this one breaks the mold. Unfamiliarity combines with an adorable ragtagginess—think “Bad News Bears”—to create an air of heartwarming spectacle.

Quality and coordination of gear runs the gamut. Some kids and parents have top-tier rides and are outfitted in color-coordinated, MTB-specific ensembles of helmets, gloves, jerseys, pants, and shoes. More than 20 students use loaner protective wear and Specialized hardtails, but otherwise look to be wearing school or gym clothes. Here and there, helmets boast stegosaurus plates or neon mohawks.

This is the South Middle School Mountain Biking Club, which is the oldest and largest of its kind in the state. Riders have gathered to take advantage of the uncharacteristically warm winter afternoon. They’ll spend the next two hours exploring feature-heavy, purpose-built trails in the adjacent 170-acre White Park. There, they get exercise and practice bike skills according to ability levels. Afterward, they meet up for post-ride reflections in small groups of five to eight.

Presently, Bartholow, 36, is consulting a clipboard and calling out names of students, chaperones, and assigned trails. New units begin to form. Each holds a short pre-ride discussion.

“We ask them to reflect on how the day went, to describe their mood, stuff like that,” says Bartholow. Participation isn’t mandatory, but most kids offer synopses. Responses range from awesome to totally crappy, from stoked to agro as heck or a little depressed. The exercise primes kids for comparing emotional states before and after riding.

Part of the club’s agenda is teaching positive emotional coping skills, says Bartholow. Focusing on having fun in a social setting while getting intensive exercise helps alleviate worries, diminish the effects of depression and stress, and bring new perspective to problems. Good endorphins combine with increased blood flow and respiration to naturally boost moods. Reflecting on differences in how they feel before and after a ride, kids learn to naturally regulate moods and develop a sense of emotional control.

“The idea is to teach kids that something as simple and fun as riding their bike can be a powerful tool for maintaining mental health,” says Bartholow.

Talks last around five minutes and conclude with a cheer. Released, kids pedal off toward trailheads in the nearby forest—early departures goof along at an ambling pace; more advanced squads celebrate with wheelies and bunny hops.

Today Bartholow, who’s raced mountain bikes since his early teens, will work with riders on jump skills using doubles and tabletops. Though he says shredding with the kids is great, administering the club can be tough.

“Keeping everything coordinated and running smoothly poses some challenges,” says Bartholow. Foremost is the volume and age of participants. Second is the club’s underlying mission to work with kids who have behavioral challenges or come from at-risk backgrounds.

Though stats aren’t official, Bartholow estimates 25-30 percent of riders fall into this category, depending on the year. Most are referred by concerned teachers or administrators; some are introduced by friends; a few are attracted by the alt-sports allure. Regardless, the diversity and focus demand more planning, administrative tact, and hands-on attention than a traditional team sports model.

“Middle schoolers are going through so many changes—physically, socially, mentally, you name it—and that’s confusing as it is,” says Bartholow. The school’s location amid a district “with high rates of poverty, obesity rates around 35 percent, and that’s just getting pummeled by [opioid and methamphetamine] abuse,” brings added complications and pressures.

To ensure he and parent-chaperones are equipped to serve the demographic, Bartholow and others have trained with National Interscholastic Cycling Association (NICA) special education experts, school counselors, and bike therapists to learn skills for effectively working with behaviorally challenged kids.

“Primarily, our goal is to provide a positive and supportive community of peers and mentors,” says Bartholow. Kids have fun in the woods, learn about stewardship through trail-building, get exercise, make friends. They also receive praise and support from adults. “Which is so important, because many of these kids don’t get that at home. And if they’re behaving poorly in class? It probably isn’t happening at school either.”

Inbuilt activities supplement before-and-after discussions to teach social and communication skills, psychological resilience, and basic life lessons. For example, say a few kids are scared of riding berms. “We’d spend an afternoon teaching them to tackle the features incrementally,” says Bartholow. Riders start on the gentle inner-curb and progress to the steep upper-lip. Encouragement helps them overcome fears and build confidence. Treating the situation as an anecdote “creates a teaching moment where we can talk about values like practice, perseverance, and self-belief.”

Another club goal is connecting kids to the larger Morgantown mountain biking community. Bartholow invites guest chaperones that include local bike club officers, bike shop owners, coaches and administrators from the West Virginia Interscholastic Cycling League (WVICL), former pro racers—in short, people with ties to businesses, groups, and organizations that bring more riding opportunities. “If a kid wants to go on a weekend ride but can’t access transportation, these are folks that will go out of their way to make it happen,” says Bartholow.

The connections are important for two reasons. First, they build a support network beyond the club. Second, they help kids practice healthy habits.

“If these kids are going to use mountain biking as a positive coping mechanism—versus drugs or alcohol, or other negative behaviors—they have to be able to ride on a regular basis,” says 40-something WVICL director Cassie Smith, one of the club’s many guest-chaperones. She’s partnered with Bartholow and others to bring South Middle’s innovative coping skills platform to the league’s 13 teams and 300-plus riders, as well as other schools. She routinely connects riders at South to WVICL squads and affiliated groups.

“The beautiful thing about mountain biking is it’s a lifelong sport,” says Smith. “That means clubs like Jeremy’s are teaching mental health skills kids can use throughout their adult lives.”

The tradition of using mountain biking to help behaviorally challenged and at-risk youths at South Middle School began with the arrival of special education instructor Jessica Harmening in 2015. At the time, the school’s MTB club, which was founded in the mid-2000s, had lapsed.

“I’d grown up mountain biking, had sort of dropped it in my 20s, but was really getting back into it,” says Harmening, now 36, whose job description includes teaching coping skills to kids suffering from trauma-based behavioral issues. She knew nature and activity-based therapies could be extremely effective. Because mountain biking combined both, sponsoring the club was a win-win: “I could share a personal passion and develop valuable tools for doing my job.”

Harmening got the idea to use bikes in this manner while earning a master’s degree in special education and working part-time at a West Virginia therapeutic foster care facility for girls. “The kids were so wound up and had so much physical energy,” she says.

Facilitating group discussions was tough; kids were quick to get defensive, act out, explode. If she could help them relax, talking would be easier and more productive. Harmening’s solution was novel. She borrowed department store mountain bikes from friends and got permission to take a small group of girls for a ride down a nearby fire road. The route was pretty and wound through a dense, quiet forest filled with creeks and wildlife. Harmening packed snacks and stopped at a predesignated turnaround to eat and talk.

Surrounded by nature, soothed by exercise, the girls opened up. But the content was brutal, their delivery disturbing. They joked about traumatic experiences suffered at the hands of adults, including violence and sexual abuse.

“It was imperative I react in a way that ensured they felt heard and respected, that showed I cared and could be trusted,” Harmening says.

Knowing the ride had a second leg gave Harmening confidence. The picnic served as a natural timer; the return journey, as a transition from emotional vulnerability to daily life. “That natural flow helped everybody feel more comfortable,” she says. They could talk and share, then return to riding and having fun. “That space was crucial. It brought time for emotional processing.”

Afterward, the girls asked about doing more rides, and, buoyed by the success, Harmening started conducting research to hone methods. What she found was astonishing.

For one, rigorous exercise offers a readymade venting mechanism and a boon of depression-battling chemicals, says licensed marriage and family counselor Joey Dolowy. He’s spent nearly 20 years using bikes to work with people suffering from depression, drug addiction, self-harm disorders, and general family or marriage issues. Riding down a forested hillside demands focus—which short-circuits habituated negative thought patterns, a symptom of depression and anxiety. Increased oxygen intake, fresh air, and simple immersion in nature brings a calming effect.

In terms of therapeutic discussion, says Dolowy, the above combines to ease defense mechanisms and boost moods, thereby increasing receptivity to suggestions and guidance.

Harmening continued leading rides throughout her tenure at the facility. At South Middle, she sought to replicate the success—and it worked like a charm. The club started with a few members and, by 2016, had grown to include about 60. Teachers began to regularly refer so-called problem students.

“For at-risk youths, or those suffering from trauma-based behavioral issues, regular participation in an activity like mountain biking can bring incredible benefits,” says Harmening. In many cases, it’s a powerful tool for connecting with kids, establishing trust, and shifting negative behavior patterns. Regardless, riding alone brings benefits.

“Riding for an hour a few times a week can drastically reduce symptoms related to attention disorders, as well as those of anxiety and depression,” says Harmening, who also notes that biking helps kids stay focused in the classroom, experience greater self-confidence, and act out less. “I can’t tell you how many teachers have come to me and said, ‘This is incredible, is [he or she] a different person?’”

Harmening left the club in 2018 after transferring to Morgantown High School. By then, though, she’d joined forces with the WVICL, which was founded in 2017. Harmening launched a team at the high school and accepted a position as the league’s Coach Supporter. With the latter, she teaches and coaches others—including Bartholow—best practices for working with riders from at-risk backgrounds and those with emotional or behavioral issues. Additionally, she’s working with guidance counselors and principals to introduce bike-related programming into more schools and establish channels for at-risk kids to access NICA teams.

“With NICA, our focus is less about competition, more about character-building,” says Smith, the league director. “Our goal is to be a resource for children and the greater community. So, working with Jessica offers an amazing opportunity that’s perfectly aligned with our mission. She’s helping us make our program one of the most supportive and inclusive in the nation.”

Bartholow assumed leadership of the South Middle School club following Harmening’s departure. Within months, he was seeking to expand its reach.

“As an instructor, I’d seen students experience positive changes before and after riding,” he says. But watching transformations up close? “It was amazing. I knew right away we needed to bring this opportunity to as many kids as possible.”

Researching ways to make it happen, Bartholow discovered the Specialized Outride program and applied for grants. A collaboration between the company and Stanford University, the nonprofit helps middle schools harness the health benefits of mountain biking. Grant recipients get a fleet of bikes, safety gear, funds for related academic programming, curriculum training for administrators, and access to additional resources.

South Middle was one of 41 schools to win a grant in 2019. Bartholow used it to establish a recurring, nine-week-long, in-school cycling and mountain biking class that teaches safety and riding skills, land stewardship, and use of exercise as an emotional coping skill. It launched last fall and was an instant hit. More than 100 students have completed the class already and 120 are on the waiting list. “The enthusiasm is mind-blowing,” says Bartholow. “Right now, it’s just me teaching the class, so availability is limited. But we’re brainstorming ways to expand.”

The success of the club and class hasn’t gone unnoticed. About a dozen middle schools have reached out to learn about applying for Outride grants and starting clubs. Bike shop owners, community organizations, local officials, and state park superintendents have asked about helping too. Bartholow is working with Smith and Harmening to channel resources and maximize impacts.

“Every kid in the state should have access to this opportunity,” says Smith, adding that West Virginia has the trails, bike culture, and human resources to make it happen. “We just have to connect the dots. [That means] disseminating information about benefits, getting schools on board, and finding new ways to fund bikes.”

The good news? Smith, Harmening, and Bartholow agree the question isn’t if it will happen, but how soon.