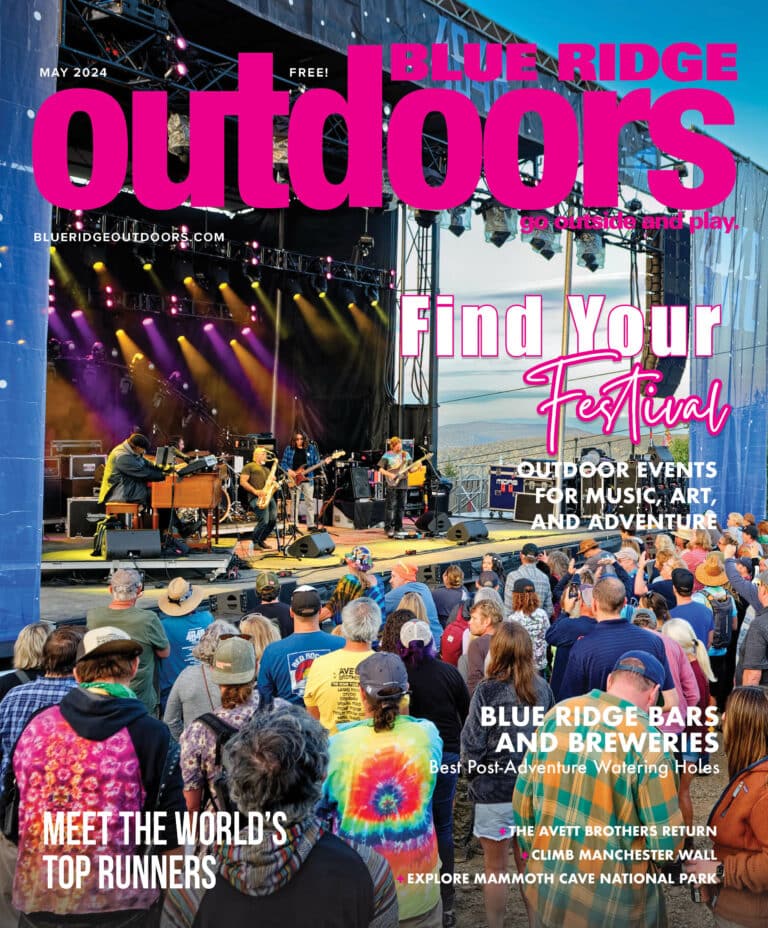

The author (left) with a fellow trail crew member in Shenandoah National Park. Photo courtesy of the Potomac Appalachian Trail Club

Stop me if you’ve heard this one. If a tree falls in the forest, and no one is around to hear it, who has to pick it up?

If the tree in question has landed on a hiking trail, the answer is probably a trail maintenance crew.

For many of us, hiking is often a solo excursion, but maintaining a trail is a team sport, one that requires a long roster and countless hours of coordination, planning, and sweating, all to ensure the trail’s very existence.

To learn more about this work—and to amend the karmic imbalance I’ve created by hiking on many but working on zero trails—I signed up for the Potomac Appalachian Trail Club’s annual summer crew week in Shenandoah National Park.

Among the oldest trail organizations in the country, the PATC was founded in 1927 by a group that included Myron Avery, one of the masterminds of the A.T. During its early days, the group scouted and constructed hundreds of miles of the trail through the Mid-Atlantic. Ninety-two years later, its volunteers are still walking those same paths, weedwackers and chainsaws in hand.

There were nine of us on the crew, hailing from every hill and dale and city block of the DC/Baltimore metro. There was a former Navy physicist, an electrical engineer, a retired lawyer, a nurse, and a Southern politician whose endless catalog of jokes filled awkward silences. Some of us were thru-hikers, most of us were not. Some of us were trail slugs (a term of endearment, I was assured), most of us were not. All of us were sharing the three rooms and one shower of an old CCC lodge, as well as the desire to do our part.

“The brilliance of trails stems from the fact that they can preserve the most fruitful of our own wanderings,” says Robert Moor, in his 2016 book “On Trails.” Our own wanderings had brought us together in Shenandoah—not just the winding roads to Skyline Drive, but every walk in the woods we had ever taken.

But by lunch on the first day, I felt unsure about the ROI of this volunteering gig. That morning I had spent three hours trailing two weedwackers, dodging kicked-up debris, and clipping overhanging branches along a mere 1.1 miles of the A.T. At the end of our slow march through the forest, the trail looked tidier to be sure, but what had we really accomplished in the grand scheme of things? In two weeks, the chickweed would reclaim its territory; the saplings would lean over the trail, ready to snag every weary backpacker who passed.

That night, as I stretched out on an old couch in the common room (my roommates were snorers) beneath an old bath towel (I forgot my sleeping bag), I wondered if my time would have been better spent elsewhere, where my labor could make a larger, more lasting impact.

The following day we were up early to build water bars (in layman terms: steps), carrying fresh-hewn logs up the mountain to bury in the earth and prevent erosion caused by unbridled rainwater. I’ve waddled on enough trough-shaped trails that this bit of work tingled with meaning.

Next it was an eight-mile hike along a frothy stream to clear blowdowns, or trees that had fallen across the trail during a recent storm. Working with a crew from the National Park Service, we stopped at each roadblock and took turns with the crosscut saw. They instructed us to pull, never push, to let gravity and the blade do all the work. With the trees out of the way, hikers wouldn’t have to circumnavigate them, creating sloppy detours through sensitive flora.

Then it was on to swales, another way to move water off the trail by creating a trench and berm from dirt that’s already there. We worked so that after a few days of wind and water and footfalls, this drainage system would look like it belonged there, allowing whomever might pass a walk seemingly uninterrupted by human activity. According to Moor, the best trail work is “meticulous construction, artfully concealed.” Here’s hoping.

On the last day, a PATC crew-week veteran taught me how to weed strategically, how to direct traffic away from sloping ground or switchback shortcuts. In this way, we could heal the damage caused by the impulse of tired hikers. That day I also learned that weeding, whether whacking or lopping, is about maintaining a navigable trail—and protecting travelers from Lyme-carrying ticks. A properly maintained trail doesn’t preserve only a dirt path, it ensures the safety of those who use it, as well as the beauty it bisects. Like most things, it’s a balance. “The delicate task of a trail-builder … [is] to bring order to an experience that is by definition disordered,” Moor explains. “It is akin to catching a butterfly in your hands.” Too much intervention and the trail loses its wild allure, too little and there are consequences—for humans and nature alike.

Indeed, as the week wore on, I began to see the work differently. Tiny gestures, yes, but far from insignificant. With each drenched bandanna and stinging muscle and long car ride to another trailhead, it occurred to me what a labor of community a trail is. And I came to realize that working on the trail was more about sustaining an experience than maintaining a path. While I have never thru-hiked the A.T., I have walked on so many trails that delivered me somewhere nearer to the throbbing heartbeat of existence, where I could witness my small but startling place in this dazzlingly complex world. The impetus behind the grueling and tedious work of trail maintenance, I finally understood, is to make certain that others have those same transformative opportunities.

Moor concludes his tome on trails by saying, “We are born to wander through a chaos field. And yet we do not become hopelessly lost because each walker who has come before us leaves a trace for us to follow.”

The paradox of the trail is the paradox of being alive: we walk alone, on paths others have made for us.

There are 31 trail clubs that do similar work along the AT, and countless others on trails around the region. So, the next time you hear about a tree falling in the forest—literally or philosophically—consider joining your fellow trail slugs to help clear the way.