Through efforts of foundations and young artists, this regional form of music is staying alive and still finding an audience.

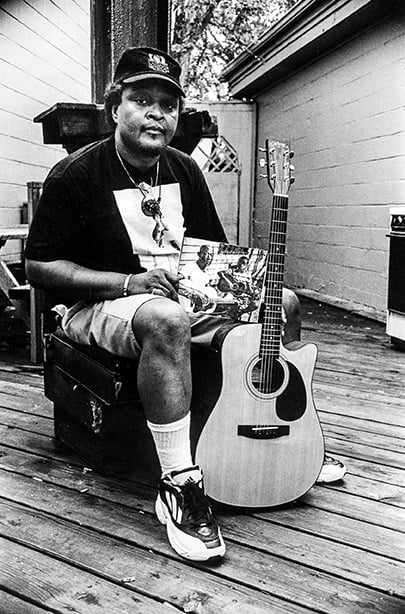

Sometimes, all it takes is a thumb and forefinger for Alvin “Little Pink” Anderson to be with his father again.

Anderson, 66, is the son of late blues guitarist Pink Anderson, who died in 1974. There are times when Little Pink picks up an acoustic guitar and gets into what he calls a “zone,” where he feels like he’s alongside his father again.

“The best zone in the world is when subconsciously you kind of drift back into the past while you’re performing,” Anderson said. “Sometimes, I can see me and him sitting there playing together.”

That’s the power of Piedmont blues, a style of guitar playing that’s often passed down through generations of a family. The style has waned in popularity as the years have gone by, and as the giants of the genre have died. Artists and enthusiasts are doing what they can to preserve the genre through a two-pronged approach — honoring the past while finding ways to connect with modern listeners.

Piedmont blues (also referred to as East Coast blues or Southeastern blues) originated in the Piedmont region of the East Coast, which stretches roughly from Atlanta to Richmond, Va. It is instantly recognizable by the fingerpicking pattern. The acoustic guitar serves as percussion, bass, and melody as the player’s thumb strums the lower strings for the bassline and the other fingers play the melody. This rhythmic plucking often creates a percussive slapping.

The fingerpicking style takes years of practice to master. Many Piedmont players, such as Anderson, start playing as very young children. Anderson said he started playing by the time he turned four, and was playing alongside his father at shows by the time he was five.

Willie Leebel, president of the Archie Edwards Blues Heritage Foundation, said Piedmont played a vital role in early American music. Listening to it, you can hear hints of ragtime, folk, blues, and bluegrass. “I think it’s part of our American heritage,” Leebel said.

Organizations such as the Archie Edwards Blues Heritage Foundation and the Music Maker Relief Foundation are doing their part to breathe life into acoustic blues. Music Maker is a nonprofit that financially supports aging or struggling blues artists to allow them to continue to make music. The Archie Edwards Blues Heritage Foundation is named for a legendary Piedmont player who died in 1998. When Edwards died, the foundation was formed to give his friends and fans a place to keep playing Piedmont blues. The foundation provides workshops and concerts at its venue, called Archie’s Barbershop, in Hyattsville, Maryland.

The majority of people who show up for these events are older, Leebel said. Most younger players he’s met are interested in contemporary and electric blues. One of the major reasons it’s hard for people to get into the style is that it’s hard to teach yourself the fingerpicking technique if the muscle memory isn’t ingrained from a young age.

“The fingerstyle is very intricate or difficult for some people,” Leebel said. “Generally, blues is easy to play. Piedmont is probably the most difficult style of blues to work with.”

The COVID-19 pandemic had an unexpected effect — it actually gave the foundation a chance to reach more people. The in-person jam sessions had to stop for safety reasons, so the foundation started holding them virtually. Now, players from all around the country settle in front of their webcams and start picking. Leebel said it’s been fascinating to meet people from all over who share the same passion for acoustic blues. He said the foundation will certainly continue to do virtual events even after the world returns to normal after the pandemic.

One of the out-of-town attendees is Elly Wininger, a member of the New York Blues Hall of Fame. Wininger, who lives in Woodstock, New York, has tuned in for a couple jam sessions and has enjoyed seeing everyone learning and collaborating.

Wininger said Piedmont is far from dead. It might sound different now than it used to, but she said that’s a good thing. It’s all about making the music real now, she said. “To me, ‘keeping it alive’ means interpreting and making it relevant now,” Wininger said. “There are people who are doing that, and I think that’s exciting.”

Artists such as 24-year-old Jontavious Willis are prime examples. The Georgia native has earned praise from well-known blues artists including Taj Mahal for the way he can replicate the sounds and feeling of early blues. He ties the past to the present, connecting original themes of Jim Crow-era blues lyrics and applying them to the current state of social justice and the Black Lives Matter movement.

Willis was one of a handful of young blues players who created the #RobertJohnsonChallenge in 2020, encouraging people to learn songs by Johnson, a famed Delta blues musician. The challenge was meant to help people understand Johnson better and see him in a more human light as opposed to just a scratchy voice from the past.

Anderson also believes that honoring the past is vital, but can relate to younger artists as they search for their own voices. He said he hasn’t been fond of most people’s attempts to modernize the music, as he doesn’t feel like many present-day songwriters truly understand the blues. “I really don’t think it’s dying,” Anderson said, “but I think it’s stuck.”

At the same time, Anderson has spent his whole life interpreting music in his own fashion. Though his father taught him how to play the guitar a certain way, he also encouraged him to take his own path. Anderson took that lesson to heart, making a name for himself as an electric blues player in addition to his acoustic roots.

“He taught me that everybody, every musician is an individual,” Anderson said. “And he used that to take that step on your own. I can ride his coattails, but only so far. That was the lesson, and to have some individuality, your own mind.”

Perhaps the future for Piedmont blues, or any form of music, is rooted more in individuality than in anything. Whether you’re playing with people via Zoom call or strumming alone or playing a sold-out concert, as long as the music is authentic and coming from somewhere within you, it can never truly die.

Cover photo: Alvin “Little Pink” Anderson. Photograph by Tim Duffy/Music Maker Foundation