Kurt Kornegay won’t tell me where “Fat Man’s Misery” is. “Misery” is the name Kornegay gave to a boulder-choked slot canyon inside Panthertown Valley that very few people have ever explored. “It’s off the side of Blackrock Mountain. That’s all I’ll tell you,” Kornegay says.

Apparently, the man still has some secrets. It’s ironic considering he is probably best known for helping to transform Panthertown Valley from a locals-only secret stash of trails into one of the most beloved recreation areas in the Southeast. Kornegay created the first map of the area, the “Guide’s Guide to Panthertown Valley,” which details Panthertown’s user-created trail system and unique bogs, peaks, and waterfalls. The map gives a wide variety of users enough information to explore this remote Western North Carolina valley on their own.

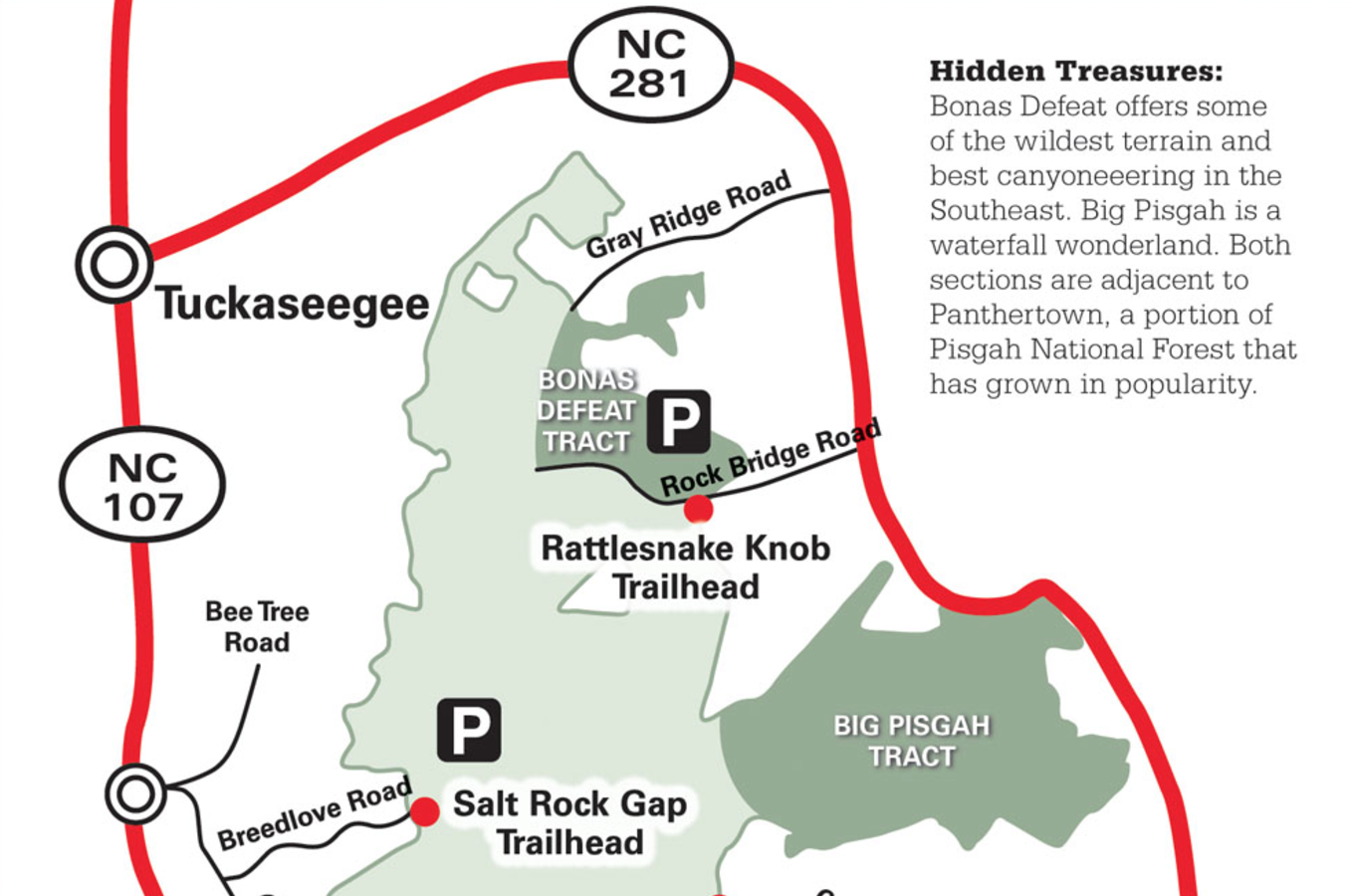

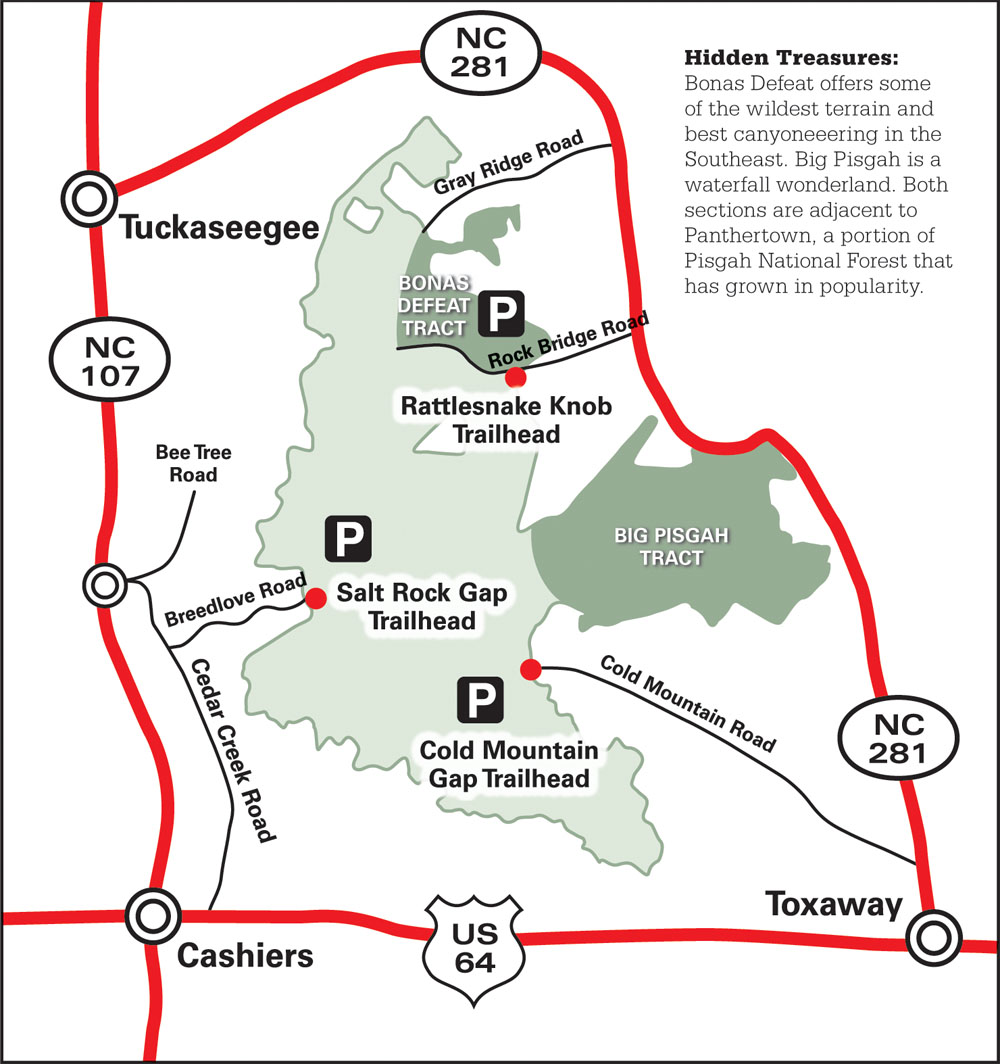

Now, the veteran guide hopes he can do it again. Kornegay has recently published an updated map to Panthertown that features two “new” adjacent tracts of land, Bonas Defeat Gorge and Big Pisgah Mountain, large swaths of forests that only locals were privy to in the past. While Kornegay’s desire to introduce more people to these under-used forests is surprising, what’s downright shocking is that there are still pockets of forests in the Southern Appalachians that haven’t been thoroughly explored and accurately mapped yet. Within these two relatively small tracts of land, there are rock faces that have never been climbed, faint trails that have never been mapped, even waterfalls yet to be named.

Big Pisgah Mountain is only a 30-minute drive from downtown Brevard, but it’s miles away from the famous singletrack and rock faces that have turned Brevard into a hub of outdoor adventure. Big Pisgah is roughly 1,500 acres of steep slopes and tight mountain streams sitting in the far southwestern corner of the Pisgah Ranger District, where the Pisgah National Forest meets the Nantahala National Forest.

On his new map, Kornegay shows only one trail cutting through the northern edge of Big Pisgah. He’s named it West Fork Way because it follows the West Fork of the French Broad as it meanders through a narrow valley floor. The trail begins at a dilapidated Forest Service gate and follows an old roadbed, which has reverted back to singletrack. It contains numerous creek crossings and massive blowdowns left from last winter’s storms. The U.S. Forest Service doesn’t recognize West Fork Way as an official trail, so there is no regularly scheduled forest service maintenance.

“I don’t see a lot of people venturing into that area, including the Forest Service,” says Nina Elliott, executive director of the Friends of Panthertown, the volunteer group that works with the Forest Service to manage Panthertown. Even though Big Pisgah is adjacent to Panthertown’s popular trail system, trail crews don’t wander into Big Pisgah.

It’s shocking, given the proximity of the mountain to urban centers and popular recreation areas. A luxury second home community sits on the shores of Lake Toxaway, not five miles from the trailhead. Drive 30 minutes farther, and you’ll be in the heart of downtown Brevard. Ten more minutes and you’re sitting at the trailheads for Davidson River and Mills River Recreation Areas, two of the most popular trail systems in the Southeast. Some surmise that the area gets little traffic precisely because of its proximity to such popular trail systems.

It’s shocking, given the proximity of the mountain to urban centers and popular recreation areas. A luxury second home community sits on the shores of Lake Toxaway, not five miles from the trailhead. Drive 30 minutes farther, and you’ll be in the heart of downtown Brevard. Ten more minutes and you’re sitting at the trailheads for Davidson River and Mills River Recreation Areas, two of the most popular trail systems in the Southeast. Some surmise that the area gets little traffic precisely because of its proximity to such popular trail systems.

“People don’t explore,” says Joe Moerschbacher, owner of Pura Vida Adventures, a multi-sport guiding operation based in Brevard. “And around here, they don’t have to. There are so many trails and waterfalls already on the maps and in the guidebooks that most people don’t feel the need to look for new adventures.”

Rich Stevenson specializes in finding new adventures—especially new waterfall adventures. The Asheville-based waterfall photographer estimates he’s discovered and unofficially named 40 to 50 significant waterfalls in North Carolina and South Carolina that aren’t listed in any maps or guidebooks. Big Pisgah, which only has one officially mapped and named waterfall (Dismal Falls), is ripe with waterfall discoveries, he says.

“We found a 70-footer on accident,” Stevenson says. “It was actually pretty easy to get to, but it’s on an unnamed creek that isn’t on any map, so most people don’t know it’s there.”

Stevenson named that 70-footer Rhapsodie Falls. He and a friend had stumbled upon Rhapsodie while bushwhacking towards Dismal Falls, which turned out to be more of a challenge than they’d expected.

“Once you get off that main trail, Big Pisgah is a wicked area,” Stevenson says. “Getting to Dismal Creek Falls was brutal. You have to bushwhack steep slopes, then drop into an even steeper gorge, then boulder your way up to the falls.”

Stevenson spends much of his time trying to pinpoint those undiscovered treasures by researching topographic maps, looking for a convergence of contour lines.

“When you see those lines run together real close, that means it’s steep. If there’s a blue creek running over those steep lines, you’re likely to find a waterfall,” Stevenson says. But you’ve got to be willing to hunt for these treasures through severe terrain. In the book Land of Waterfalls, author Jim Bob Tinsley calls Big Pisgah and Dismal Creek “one of the most foreboding places in the Southern Appalachians.”

And Bonas Defeat Gorge is even wilder.

“Old timers say it’s like hiking through the barrel of a shotgun,” says Kornegay, referring to the terrain inside Bonas Defeat Gorge. Not only is the gorge narrow and steep, but the river is prone to flash floods and spillover from the dam upstream. It’s as close to a true canyon that you’ll find in the Southeast, with a massive 400-foot rock wall, and house-sized boulders and caves lining the river floor. American Whitewater considered negotiating for recreational releases on the river, which drops 240 feet in under half a mile. After a non-boating test flow of the gorge, some of the best boaters in the state concluded the Bonas Defeat was “inordinately dangerous.”

Hiking the gorge can be equally fraught with peril.

“There’s no trail, so you’re basically bouldering and spelunking your way up the riverbed,” Kornegay says.

Bonas Defeat is dammed, but still has water in it from a few feeder streams, which makes the rocks slick, and any amount of rainfall can raise the water level, making navigation even more challenging. Accessing the gorge can be just as tough, as it is surrounded by private land.

“The difficult access and terrain automatically limits the number of people who can enjoy it,” says Mike Milkins, the district ranger for the Nantahala National Forest. Milkins himself hasn’t even been inside the gorge.

Professional guide Joe Moerschbacher ran an exploratory trip into Bonas Defeat and concluded that it was some of the best canyoneering in the Southeast. It boasts swimming holes, rock jumps, and a 150-foot waterfall rappel on Wolf Creek Falls.

But the Forest Service denied Moerschbacher’s permit request to guide trips in the gorge, presumably because the terrain is too severe.

“It’s a world-class day hike, one of the best around,” says Burt Kornegay. “But it’s not for everybody. If a lot of people start trying to hike Bonas Defeat, there are going to be a lot of injuries.”

Still, Kornegay hopes his new map will encourage more people to explore Bonas Defeat and Big Pisgah, the way his previous map beckoned them to Panthertown. Of course, dishing local secrets to the masses doesn’t come without controversy. Many local bikers and hikers who had Panthertown’s trails all to themselves still lament the area’s popularity boom.

“Old timers who’ve been hiking Panthertown since the mid-80s thought it was their best kept secret. They would’ve liked to build a wall around it and keep it to themselves,” says Nina Elliott of Friends of Panthertown. “But the word is out big time. People know about Panthertown. On a weekend in the summer, it can be a zoo.”

Kornegay knows he’s partly responsible for that zoo, but he’s unapologetic.

“It’s true, Panthertown is more heavily used now. Some trails show more wear. There are new campsites all over the valley that didn’t used to be there,” Kornegay says. “I know a few people loved it when they had it all to themselves. I’d like to keep these areas to myself too, but it’s unrealistic. In the East, our forests aren’t big enough to keep secrets. Sooner or later, they’re either going to be used or logged. I’d rather see these forests hiked. A thousand backpackers can do some damage to a trail, but nothing like a bulldozer. Try to log Panthertown now. There would be an uproar because it’s so loved. Ten years ago, though, not many people would have known or cared.”

Even though Big Pisgah and Bonas Defeat are connected with the now-popular Panthertown, these two outlying tracts are a different animal altogether. More users will inevitably find their ways into the areas because of Kornegay’s map, but it’s doubtful that the masses will respond to Big Pisgah and Bonas Defeat the same way they responded to Panthertown. There may be just as many waterfalls, cliffs, and bogs inside the Big Pisgah and Bonas Defeat tracts, but you still have to bushwhack off-trail to find them.

“You’ve got to go rock-hopping up a creek or crawling through rhododendron to find these things,” Rich Stevenson says. “The average person isn’t going to do that.”

HIGHLIGHT REEL

Want to explore these tracts on your own?

Kornegay’s map is essential, as is common sense. Be smart, never travel alone, and always pack for the worst. Order a map through Slickrock Expeditions.

BIG PISGAH

West Fork Way follows the creek for three miles before connecting with the Devil’s Elbow Trail on the edge of Panthertown Valley.

Aunt Sally’s Falls: At .5 miles from the trailhead, you’ll begin to hear this 40-footer from the trail. Take a short bushwhack north through briars and scrub brush to the base of the falls.

Rhapsodie Falls: After a mile of hiking West Fork Way, you’ll pass through a tall stand of white pines. When the trail splits, take the left split south and cross the creek and pick up the trail again, passing a small 20-foot waterfall on the way. Follow a faint trail up the right side of the creek to Rhapsodie Falls.

BONAS DEFEAT

Wolf Creek Falls: This 150-foot waterfall drops over carved bedrock at the top of Wolf Creek Gorge. From the parking area off Hwy 281, follow the obvious trail to the riverbed, then look for steep scrambles to the top and base of the waterfall.

Doe Branch Path: This collection of forest roads traverses the forest south of the gorge, between Tanassee Lake and Rock Bridge Road, where you’ll find a parking pull off.

Bonas Defeat Wall: Deep in the middle of Bonas Defeat gorge is a 400-foot rock wall with a handful of established climbing routes.

Grandma’s Kitchen: This collection of cascades drops through smooth, perfectly round potholes inside the gorge.