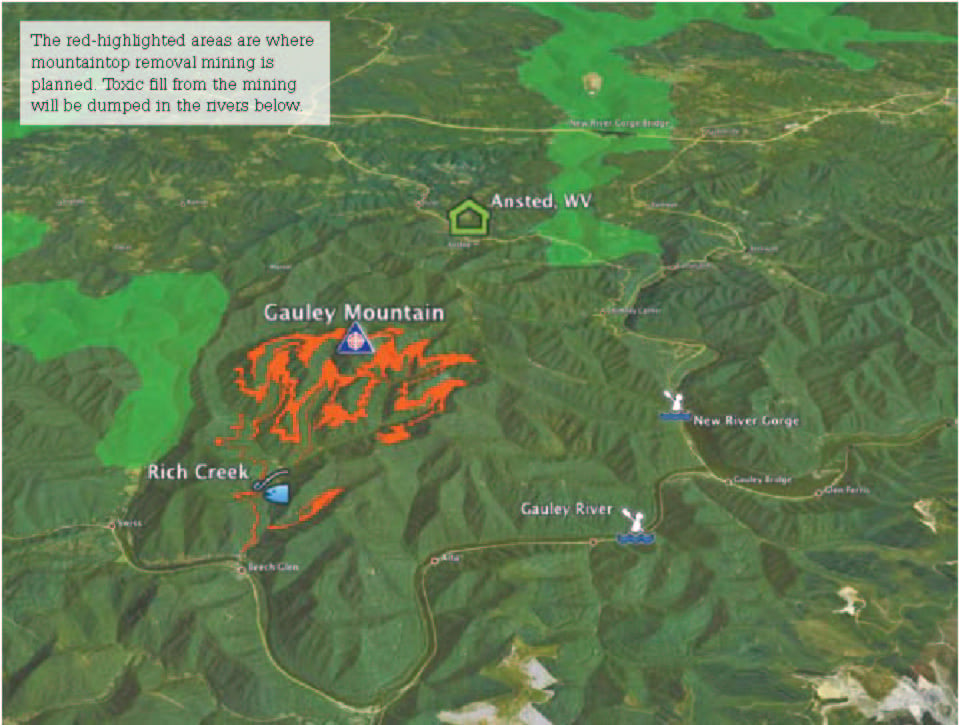

If you’re one of the hundreds of thousands who flock to the New and Gauley Rivers each year for a whitewater rafting trip, you may hear something louder than the roar of the rapids: the sound of dynamite blowing off the top of Gauley Mountain. Permits have been issued to Powellton Coal Company to blast Gauley Mountain for mining. Access roads have been gutted. Trees have been felled.

Sign the petition to stop mining on the Gauley Mountain here.

Mountaintop removal mining already has devastated much of West Virginia, but Gauley Mountain could set a new precedent in just how far this irreparably alarming industrial practice could extend its reach. The mountain sits right between the revered New and Gauley Rivers and borders a federally designated national recreation area. This is the Mountain State’s epicenter of rock climbing and whitewater recreation. It’s a booming tourism spot that attracts 275,000 annual rafters, who bring millions of dollars to more than 40 independent outfitters and local businesses.

“We’re keeping an eye on the development of this for possible impact,” says Mark Lewis, director of the West Virginia Professional Outfitters. “We are always concerned with anything that could impact our guest experience.”

Beyond scarring a beloved natural resource and turning away tourists, mining will endanger the health and livelihoods of locals. The small town of Ansted is situated directly between the New and Gauley Rivers. The once-bustling mining town was abandoned in the 1950s, but in the past two decades it has made a comeback as a tourist destination for the recreation opportunities in its backyard. The town is planning to build a trail that would connect the New and the Gauley Rivers.

Citizens are fearful that mountaintop removal will quickly degrade the scenic appeal that has recently returned to town. They have formed the Ansted Historical Preservation Council specifically to fight the mining project. Town mayor Pete Hobbs has boldly voiced his disapproval—something most politicians in West Virginia won’t do when it comes to King Coal. The council initially became concerned about the mining when word broke about a proposed coal-haul road that would run right near an elementary school. West Virginia has a long history of fatalities at the hands of big-freight trucks that carry tons of coal. Permits say the trucks could run through town 24 hours a day. The Ansted Historical Preservation Council conducted a study for a 100-megawatt wind farm on Gauley Mountain and discovered that it could bring in nearly as much county tax revenue as coal severance.

“Coal will go out in 15 to 20 years, but wind will be here forever,” says Cary Huffman, an Ansted resident and former miner. “We’re just a group of citizens coming together, just trying to save a little bit of the beauty we have now. I have grandkids, and if we take the tops off of the mountains, they won’t be able to roam the woods like I did growing up.”

——

Sign the petition to stop mining on the Gauley Mountain here.