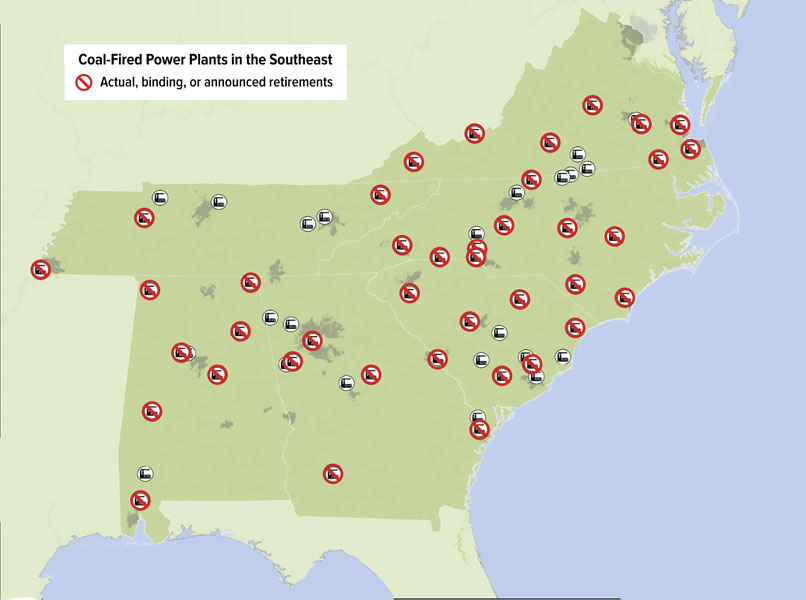

Ten years ago, King Coal reigned supreme. The Southeast’s electric companies operated 246 coal-fired power plants and planned to build another nine units.

Today, utilities plan to retire or have already retired 126 of those coal-fired units, and they have shelved plans for seven of the proposed units.

How did this happen—especially in the heart of coal country?

“There are basically three driving forces behind this trend: changes in technology, changes in economics, and changes in regulation over the past few years,” says Jonas Monast, director of the climate and energy program at Duke University’s Nicholas Institute for Environmental Policy Solutions.

On the regulatory front, one important driver was EPA’s 2011 Mercury and Air Toxics Standards Rule, which requires power plants to substantially limit their emissions of toxic air pollutants like mercury, arsenic and heavy metals. The rule forced utilities to install the most effective pollution controls available, essentially making them pay for the pollution created by burning coal by internalizing the costs of using it as a fuel. Faced with these installation costs, utilities in the six Southeastern states decided instead to shutter 58 old, inefficient coal-fired units.

State laws have played a role as well. The 2002 North Carolina Clean Smokestacks Act required the state’s 14 coal-fired power plants to reduce by three-quarters the emissions of nitrogen oxide and sulfur dioxide—the main pollutants responsible for ozone, smog, acid rain and other air quality problems. Power companies achieved those cuts by installing $2.9 billion worth of scrubbers and other pollution controls, as well as closing many older coal-fired power plants. Utilities have shuttered seven coal-fired power plants in North Carolina since 2011 and slated another three for retirement or conversion to other fuel sources by 2020. These pollution controls and closures have reduced North Carolina’s carbon emissions from electricity by 27.4 percent and mercury emissions by 70 percent.

Replacing Coal

At the same time that federal and state regulations are making coal-fired plants more costly to operate, other sources of energy, particularly natural gas and renewables, have become less expensive.

Duke Energy has already retired about half of its Carolinas coal fleet, shutting down units at 11 coal-burning power plants. In their place, the company has built two combined-cycle natural gas plants, which generate up to 50 percent more electricity than traditional plants by routing waste heat from the gas turbines into a nearby steam turbine. The Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA), South Carolina Power & Gas, and Dominion Virginia Power also plan to replace coal-fired plants with natural gas units.

“Natural gas is a more attractive fuel source because federal policy is not friendly to carbon, and coal emissions generate carbon,” says Dominion spokesman David Botkins.

Renewables are also playing an important role in the Southeast’s clean energy economy. For example, North Carolina has 1 gigawatt of installed solar power in the state, making it fourth nationally in installed solar, and is also home to one of the South’s first large-scale commercial wind farms, the Amazon East Wind Farm, which is expected to start producing power by the end of the year.

And some utilities are relying on renewable energy sources from other parts of the country to boost their renewable portfolio as well. Since wind power has proven difficult to develop in much of Tennessee, TVA has contracts to purchase more than 1,500 MW of wind capacity from the Midwest, in addition to purchasing wind power from the 27 MW Buffalo Mountain Wind Energy Center in Oliver Springs, Tenn.

One factor driving the switch to cleaner-burning energy is EPA’s Clean Power Plan, which sets state-specific targets for achieving a 32 percent reduction in the nation’s carbon emissions. The Supreme Court temporarily stopped the plan in February, ruling in an ideologically split decision that EPA can’t implement the plan until the courts settle the legal challenges against it. A coalition of 24 states—including Alabama, Georgia, North Carolina and South Carolina—are challenging the plan, questioning EPA’s authority to impose the regulations and some of the plan’s specifics, such as its use of 2012 as a baseline year, after many states had made significant progress in cutting CO2 emissions from coal-fired plants.

Map courtesy of Southern Environmental Law Center

Benefits for Health and the Environment

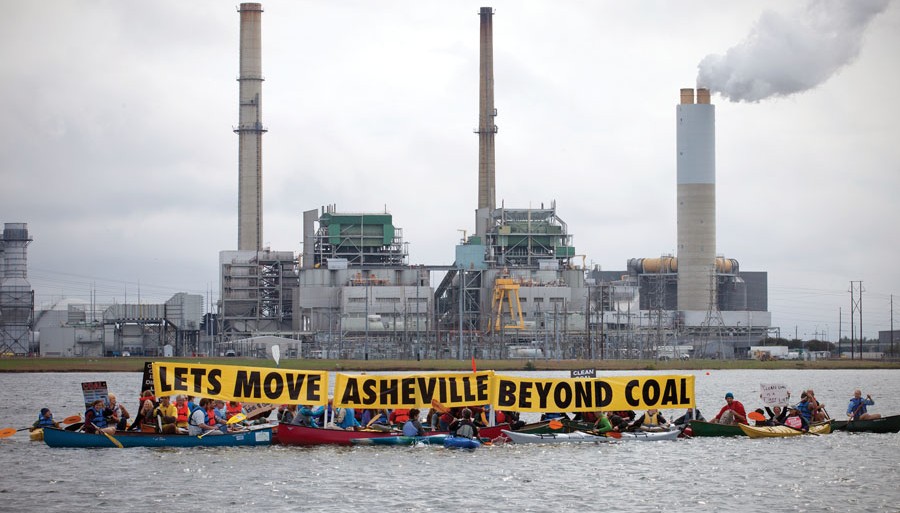

Outdoor organizations and public health groups are hopeful that cutting back on coal will have benefits for human health and the environment.

“Someone who’s in the hiker community and spends a lot of time active in the outdoors may not think of themselves as at risk from air pollution in the outdoors, but it affects everyone,” says Janice Nolen, assistant vice president of national policy for the American Lung Association. She notes that several studies have shown a decline in hikers’ lung function as ozone levels rose, even at levels below EPA’s safety standard.

Less demand for coal also reduces mining and its associated environmental impacts, including habitat disturbance, water pollution, acid mine drainage, and greenhouse gas emissions.

There are also direct impacts from the coal-fired generation itself, most notably the storage of waste products in coal ash landfills and ponds, which can contaminate groundwater, wetlands, creeks, and other waterways with toxic metals that can cause cancer and neurological damage. In the Southeast alone, there are about 400 coal ash storage facilities, including more than 50 sites where there is known pollution or contamination, according to the Southern Alliance for Clean Energy. Most notably, a 2008 spill at TVA’s Kingston Plant sent more than 1 billion gallons of ash sludge pouring into the Emory River and a 2014 spill at a Duke Energy plant sent almost 39,000 tons of coal ash and 24 million gallons of wastewater into the Dan River.

David McKinney, chief of environmental services for the Tennessee Wildlife Resources Agency, noted that coal-fired facilities affect fish populations by releasing water that’s too warm for fish or killing fish when they draw water from lakes and rivers. “As the global demand for coal diminishes, eventually the environmental consequences of the extraction and preparation process should likewise diminish,” McKinney says.

The South’s dramatic reductions in carbon emissions in a single decade show that a clean energy future is within reach, says the Sierra Club’s Kelly Martin. “Transitioning to renewable energy sources will ensure we have cleaner air and cleaner water in the places we live and love to be in.”