There’s far more to the history and mystery of Grandfather Mountain than the fact that one of the East’s major mountains remained in private hands into the 21st century. Most of Grandfather is a state park now, but Hugh Morton’s Mile-High Swinging Bridge tourist attraction, immortalized in millions of vacation photos, is still privately owned and for many people, the landmark that defines the mountain’s identity.

Morton may have made an entire mountain synonymous with a swinging bridge, but Grandfather is a far bigger landmass and far bigger topic than people imagine. That’s why I decided to write a new book just published by the University of North Carolina Press, Grandfather Mountain: The History and Guide to an Appalachian Icon.

My own history with Grandfather goes back to the 1970s when I set out to find the South’s most spectacular mountain—and found Grandfather. On one day hike, I was greeted by “No Trespassing” signs. A hiker had died of hypothermia and Hugh Morton had closed the dangerous, overgrown trails. If the peaks remained off limits to the public, I knew almost anything could happen to my favorite mountain. That wasn’t the future I had in mind, so I met Morton and persuaded him to let me manage the backcountry and reopen the trails.

I’ve been hiking the mountain and writing about it ever since and after spending the last four solid years completing the “definitive book” on Grandfather, I am more impressed than ever with this singular summit.

The mountain was an attraction centuries before the swinging bridge. Native Americans hunting below the peaks thought they saw rocky, human-like faces peering back at them. Early white explorers followed, and so did some of the most iconic incidents of Appalachian exploration. Even Daniel Boone was lured west tracing the mountain’s tempting summits on the skyline. Long before New Hampshire’s now fallen Old Man of the Mountain was noticed and named, Grandfather’s snowy profile face had already made it “the Grandfather” of the Appalachians.

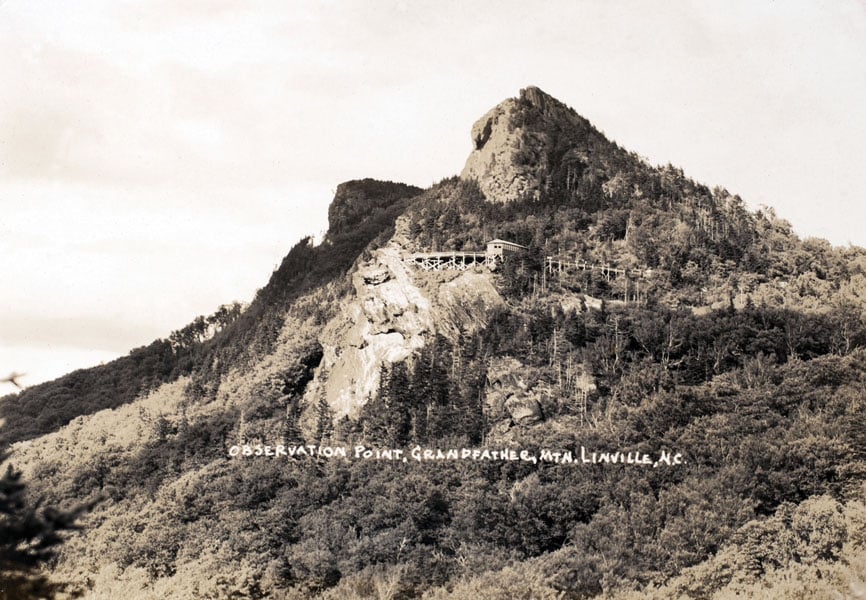

Hikers were the first tourists. Then in the 1930s, the MacRae family, who’d bought the mountain and founded Linville, cleared a rough road to a craggy view. Called Observation Point, the first commercial attraction offered a great vista and tempting trail access higher up to Linville Peak, a spectacular summit that in 1952 would anchor Hugh Morton’s swinging bridge. People still stop at that viewpoint today, and if you know where to look, a long forgotten time-warp trail still leads into the past.

I’ve been following trails like that on Grandfather most of my life, and they’ve led me to a conclusion: This monumental mountain—the most ecologically significant summit in Eastern America—is more than a swinging bridge or a highland games. If you delve into the mountain’s past as far as I have, it’s hard not to conclude that our Grandfather is the most iconic peak in the entire Appalachian range.

I can only scratch the surface here, but let’s visit a few places to sense some of that symbolism.

Secrets in the Attic

From the mountain’s three highest peaks, MacRae Peak, Attic Window Peak, and Calloway Peak (the highest at 5,946 feet), there’s a dramatic, almost vertical mile drop-off to the Piedmont. That Rocky Mountain-like relief has inspired some climbers to song, including Andre Michaux in 1794. John Muir, the future “father of the national parks,” sang out on the summit in 1898. A man so inspired by Yosemite had one of his most moving wilderness experiences in North Carolina.

Attic Window offers an awesome view, but in this attic, there’s a secret window. Halfway up the hand-over-hand climb of the peak’s cloven face on the Grandfather Trail, there’s a crack off to the side that leads to a ledge-top seat on a cliff face looking west. It’s not easy to find, and tricky to explore, but it’s been an adventure for generations.

This entire area around the mountain’s middle summit, Attic Window, is awesomely alpine and attractive to campers for two of the mountain’s best designated campsites. Neither see as much use as some. Attic Window’s tent platform perches atop a sheer dome hundreds of feet high with a spectacular nighttime view of cities sparkling across lowland North Carolina. This campsite is easiest to reach from the Black Rock trailhead in the swinging bridge attraction, especially if you take the Underwood Trail and bypass climbing over MacRae Peak. But with no overnight parking permitted inside the gate, you’ll need to get dropped off and picked up to camp. You could also just get dropped up top and hike down to a car spotted at one of two valley trailheads. The bottom of the Profile Trail is on NC 105 near Banner Elk, in the west. The Daniel Boone Scout Trail leaves the Blue Ridge Parkway, in the east.

Neither hike from the valley is an easy amble. Luckily, from either trail, there’s another great campsite before you get to Attic Window. Caught between two whaleback clifftops, Alpine Meadow campsite is a breezy treeline-like gap with crags perfectly placed for sipping tea at sunset. The site was recently designated for group camping and is reservable on the state park’s website. If there’s not a Boy Scout troop headed there—and it was a Scout troop that built the Grandfather and Boone trails during World War II—you might have it to yourself.

Even if you gain a lot elevation by car and start at the swinging bridge as many people do, Attic Window and beyond can be an ambitious day hike. If you’re crunched for time, at least take the mountain’s classic loop hike over MacRae Peak, the first summit that towers over the attraction. From the Black Rock Parking Area, reach the Grandfather Trail and scale the famous ladders up MacRae’s sheer faces, then circle back on the Underwood Trail. Rock climbers won’t flinch, but even experienced hikers will get sweaty palms making many a tricky traverse from ladder rungs and cables to rock. That’s especially true at the summit boulder teetering on the skyline. As you sit on top and survey the endless scene, be glad you weren’t sitting there in a 1980 cloud bank when an airplane smashed into that very rock.

Before tackling Grandfather’s upper elevations, search the websites for the state park and the Grandfather Mountain Stewardship Foundation that runs the private attraction. Be sure you’re not one of many people who confuse the rules and policies of these two very different entities. A few caveats. Even if you start at the attraction to hike into the state park, you still need to pay the entry fee to drive up the road. If you hike from the state park’s valley trailheads, no hiking fee is charged. And if you reach the attraction, that’s OK; you won’t be charged to cross the swinging bridge. But hiking there, and especially hiking back, is an arduous enterprise that many underestimate. If you can’t hike back, anyone you call to drive to the top and rescue you will also need to buy a ticket.

Bowled Away

There are precious few spots in the Southern Appalachians where virgin forest still holds sway. Early 20th century federal records maintain that Grandfather’s towering virgin spruce and fir forest was quite arguably the most scenic, significant tract of virgin timber in the entire South. Sadly, it fell to the loggers’ saws. Post-timbering, the foothills were such a wasteland they became the first national forest in the East. Only later did loggers swarm Grandfather’s peaks.

A great place to sense that past is beside the Blue Ridge Parkway in what I dubbed the Boone Fork Bowl on 1970s trail maps. The spectacular valley below Calloway Peak was the only place on the mountain where a railroad ever gouged out a grade. Hike the gradual Nuwati Trail and you’re following the long-ago, still visible path of the train tracks. The sharp-eyed may spot some stray logging cables on the way. At the end of the trail, Storyteller’s Rock offers a great view of this wild area. A few tent platforms are clustered nearby.

Unlike the rugged terrain at the top of the ridge, the valley of Boone Fork offers easier access, so day hikers heading to the view have an easy walk. To add more distance and spectacular scenery, include a side loop up the Daniel Boone Scout Trail and down the alpine vistas of the Cragway Trail. That opens up other camping spots that are rarely occupied on weekdays.

The highest peaks of Grandfather were eventually logged. In 1902, Teddy Roosevelt’s administration lamented that virgin timber in the Southern Appalachians was “only saved from entire destruction by the generally scattered distribution of the merchantable timber.” Grandfather was a poster child for that point. So much timber was compromised by the harsh climate or protected by cliffs and crags that trees were left to reseed the slopes. Hints of the virgin past still hide in rugged out-of-the-way parcels.

Many times, finding my way to these secret spots, I stumbled upon the remains of old logging camps. Over years of maintaining the mountain’s trails in my youth, I used many of the same tools as loggers long before me. Standing alone in the woods in wet wool, beaten up and defeated by the power of the mountain, I often went home to wood heat fearing for Grandfather’s future. After enduring a disastrous “haircut” in the 1920s (only to grow back a new crown of evergreens), and a “swinging bridge” strung between summits in the 1950s (mercifully placed between lower peaks), resort developments were still being proposed for Grandfather’s backcountry as recently as the 1990s. Thankfully, state park status in 2009 means that Grandfather has likely outlasted the worst of past challenges.

Margaret Morley, one of the great early chroniclers of the Appalachians, begged the loggers to be merciful in her 1913 book The Carolina Mountains. She urged leaving trees to “preserve those picturesque skylines,” for who, she asked, “can wait a hundred years for the trees to grow again?” Morley’s gone, those years have flown, and all across my favorite mountain the rich ecosystems of the ancient past reassert themselves.

As Grandfather faces a bright future of preservation in perpetuity, I decided to write an homage to the old man. Now is the perfect time to gaze back on, and out from, a mountain whose very name makes it a patriarch of our collective family. It’s time to visit your Grandfather.

Randy Johnson serves on the Grandfather Mountain State Park Advisory Committee. He’s also task force leader for the Grandfather Mountain to Blowing Rock portion of the Mountains-to-Sea Trail.