A decade ago, the term “farm-to-table” was hardly a phrase at all. Locally minded restaurants weren’t uncommon, but they certainly weren’t sought after. Now, as consumers grow increasingly conscious of where their food comes from, the restaurant industry has become saturated with “locavore.” Often-false claims plaster street signs and websites, citing “farm-fresh,” “organic,” “non-GMO,” and “responsibly grown,” “locally” sourced ingredients as mainstays of eateries both big and small. It’s a source of controversy, and sometimes you’re being fed fiction, but it’s a marketable one at that.

For the restaurants that are truly walking the talk, the misleading assertions are certainly frustrating, but, as Asheville-based Early Girl Eatery co-owner John Stehling says, “Your track record will speak for itself.”

See what Stehling and three other regional farm-to-table restaurant owners have to say about the ups and downs of managing a locally mindful restaurant.

Roanoke, Virginia

When Diane Elliot bought Local Roots from her son back on the spring equinox of 2009, she had no restaurant experience. She had been a spiritual healer, Native American storyteller, ordained minister, childbirth educator—but restaurant owner?

“Having a restaurant was not only at the bottom of the list, it wasn’t even on the list,” she says.

But when her son confessed he was ready to sell the locally minded, Roanoke-based restaurant just a year and a half after opening, Elliot couldn’t bear to see it go. She took the leap and never looked back. “Though I was doing spirituality work, [having a locally minded restaurant] was related because this is about people’s connection to the earth,” Elliot says. “Farm-to-table means you’re eating seasonally. You’re not eating strawberries in the middle of January.”

“Though I was doing spirituality work, [having a locally minded restaurant] was related because this is about people’s connection to the earth,” Elliot says. “Farm-to-table means you’re eating seasonally. You’re not eating strawberries in the middle of January.”

Elliot sources nearly 90 percent of Local Roots’ ingredients from local farmers, and almost half of that comes from the Floyd-based food aggregator Good Food, Good People. The restaurant composts everything it can’t pickle, and makes nearly everything from scratch save for the ketchup. Just four blocks away from Local Roots is the restaurant garden, which Elliot anticipates will produce enough extra produce to sell at the local organic market this summer.

She admits that not everything at Local Roots is truly local—after all, where in the Blue Ridge can you grow lemons and catch seafood? Elliot compromises by, at the very least, ensuring that her ingredients are sustainable, organic, local, and/or ethical, a guiding principle she coined “SOLE” food. In the long run, Elliot hopes to have an onsite greenhouse where she can grow her own lemons and limes, but more importantly, she hopes to see a more widely accepted consciousness about food in the Roanoke community.

“For me, this is not a trend,” Elliot says. “For me, it’s my dream that people learn and understand that eating right is better for them and better for the earth. Taking care of your earth takes care of you.”

Trace a Dish to its Roots

Braised Rabbit Pappardelle

Pasta flour (Anson Mills, Columbia, S.C.)

Eggs (Jamisons’ Orchard Farm Market, Roanoke, Va.)

Milk (Homestead Creamery, Wirtz, Va.)

Olive Oil (Georgia Olive Farms, Lakeland, Ga.)

Salt (JQ Dickinson Salt-Works, Charleston, W.Va.)

Rabbit (Polyface Farms, Swoope, Va.)

Ramps (Wild West Virginia, W.Va.)

Carrot Top Pesto (Riverstone Farm, Floyd, Va.)

Chevre (Curtin’s Dairy, Salem, Va.)

Butter (Homestead Creamery, Wirtz, Va.)

Marjoram + nasturtium leaves (Chestnut Grove Farm, Bent Mountain, Va.)

Asheville, North Carolina

With two kids and two restaurants, which, really, are basically children, Early Girl Eatery owners John and Julie Stehling don’t have a lot of leisure time. From creating unique and daily Early Girl specials to expanding farm relations and experimenting with ingredients, the Stehlings care about what food they put on your plate, and it shows. Founded in 2001 long before restaurants started staking claim to “farm-to-table” and “locavore,” Early Girl Eatery in downtown Asheville has won the acclaim of such widely read publications as Southern Living, Bon Appetit, The New York Times, and USA Today. Its reputation is hard earned. One year before John and Julie even opened Early Girl’s doors, they were already networking and building the community of farmers who would later supply the restaurant’s ingredients.

Founded in 2001 long before restaurants started staking claim to “farm-to-table” and “locavore,” Early Girl Eatery in downtown Asheville has won the acclaim of such widely read publications as Southern Living, Bon Appetit, The New York Times, and USA Today. Its reputation is hard earned. One year before John and Julie even opened Early Girl’s doors, they were already networking and building the community of farmers who would later supply the restaurant’s ingredients.

“We were going to farmers’ markets and tailgate markets and finding out who’s doing what and then we’d go out and visit them at their farm,” says John Stehling. “Now, these same people are my friends. I live here at the restaurant. It’s part of me. I hang out with Walter who makes my jam, Andy at Looking Glass Creamery who makes my cheese. We build friendships, and we have children that are similar ages. It’s a community and that’s what I love about Asheville.”

Initially, Stehling says, things started out small. A handful of farmers provided meats, a little cheese, some produce. Now, 15 years later, Early Girl works with over 30 farmers at any given time, and according to Stehling, there’s room to do more.

“It’s still unfortunately more expensive to do local than commercial,” he says. “A restaurant could do strictly local items 100 percent, but it really limits you.”

Still, in the height of growing season, Stehling manages to source sometimes more than 70 percent of Early Girl’s ingredients within an hour’s drive. He says the restaurant’s founding principles were never a marketing ploy—establishments like Laurey’s and The Market Place were “going local” long before Early Girl. But what separates Early Girl from a lot of its farm-to-table competitors is the price point. Signature dishes like the Early Girl Benny and the Sausage and Sweet Potato Scramble come in right around $10 and the servings are hearty.

“We knew we weren’t ever going to get rich doing this, so we really just wanted to be part of the community,” Stehling adds. “We knew supporting local would really help build the community and that’s how we can give back. We provide 80 jobs and pump as much money back into the community that we can and offer a unique product that helps Asheville be who it is and that makes us happy.”

Trace a Dish to its Roots

Early Girl Benny

Eggs (Highlander Farms, Fairview, N.C., or Cane Creek Beef and Poultry, Saxapahaw, N.C.)

Grits (Boonville Flour & Feed Mill, Boonville, N.C.)

Spinach and Tomato (Mountain Food Products, Asheville, N.C.)

Meadowview, Virginia

True to its name, the quaint town of Meadowview is mostly rolling hills and bucolic farms painted against a backdrop of southern Appalachian mountain vistas. It’s charming, albeit a little behind the times, but for Emory & Henry College adjunct professor Stephen Hopp and his wife, the internationally celebrated author Barbara Kingsolver, Meadowview is home. It’s also the site of the couple’s farm-to-table restaurant, The Harvest Table, which was conceived out of the family’s yearlong stint of eating only the things they could barter for or grow. “I moved here in the ‘80s,” Hopp says. “It’s a small community and it’s underemployed. The idea was to put our money where our mouth is to create a local economy that would do something for this community. It’s done a lot, but there’s still a lot more to do.”

“I moved here in the ‘80s,” Hopp says. “It’s a small community and it’s underemployed. The idea was to put our money where our mouth is to create a local economy that would do something for this community. It’s done a lot, but there’s still a lot more to do.”

The Harvest Table works with 60 farmers, growers, and regional ranchers, but that doesn’t include one-time purveyors, if you will, like morel foragers or ramp hunters. Though the restaurant goes to South Carolina for rice, Georgia for pecans, and Asheville for trout, Hopp only includes ingredients beyond the 100-mile zone if it expands the palate and if the company operates in an environmentally friendly, sustainably minded manner.

“We won’t go to Florida to get lemons to put on the edge of your glass of water,” says Hopp. “We don’t think that’s consistent with what we’re trying to say here. We’ll get you a sprig of lemon mint out on the patio, and it’s really very similar.”

Like lemons, Hopp refuses to get feedlot meat under any circumstances. If The Harvest Table runs out of an item, they do without. Like a finely tuned seesaw, Hopp says managing a farm-to-table restaurant is a careful balance between being true to the mission and keeping the doors open. To offset any need to compromise its mission, while also supplementing some of the items unavailable in the off-season, The Harvest Table runs its very own four-acre farm just a few miles away.

The farm, managed by 25-year-old Samantha Eubanks and a rotating crop of interns, is Hopp’s legacy. The numbers seemingly don’t add up—in its almost nine years of business, the restaurant has yet to turn a profit and the $30,000 farm only brings in $25,000 worth of produce—but for Hopp, The Harvest Table model is invaluable.

“When we think about our carbon future, agriculture is a bigger player in that arena than most people understand,” Hopp says. “All of the discussion about carbon is not about taking carbon out of the atmosphere, it’s about reducing human’s excess carbon expenditure. Agriculture has the capacity to take carbon out of the atmosphere,” which, he says will be an important consideration moving forward.

Hopp wants his customers to know all of this, and care, too, yet just like the seesaw balance between running a business and staying authentic, Hopp recognizes that some customers don’t necessarily want to be beat over the head with information.

“We encourage people to ask us about the food,” Hopp says. “When they do, we engage them, but 99 out of 100 diners just want to have a nice meal and I just want them to know that it’s fresh and local.”

Trace a Dish to Its Roots

Lamb Sausage Taco

Lamb (Grandview Farms, Abingdon, Va.)

Rainbow chard (Harvest Table Farm, Meadowview, Va.)

Curry Kraut (Gnomestead Hollow, Dugspur, Va.)

Chèvre (Ziegenwald Dairy, Gate City, Va.)

Cilantro + kale flowers (Harvest Table Farm, Meadowview, Va.)

Tortillas (Made in-house with lard rendered from Fore Family Farm, Glade Spring, Va.)

Frostburg, Maryland

For a city once fueled by the mining and transportation industries, Frostburg, Md., is making strides to a newer, greener identity. Despite its close proximity to metropolitan centers like Washington, D.C., Baltimore, and Pittsburgh, this town of 9,000 is situated at the heart of the Mid-Atlantic farming community. With backdoor access to the 54,000-acre Savage River State Forest and Great Allegheny Passage (of which, it is an officially designated Trail Town) as well as an in-town state university, Frostburg is primed for a new wave of energy.

SHiFt, a farm-to-table eatery located just two blocks off Main Street, is part of that movement. Co-owner Jes Yowell is a graduate of Frostburg State University. She says that showcasing the natural assets surrounding Frostburg was first and foremost a mission of SHiFT.

“We really wanted to showcase the beauty of this land and living off what we have instead of what we want,” Yowell says. “It’s easy to open up the Cisco catalogue and say, ‘I want all of these things,’ but I didn’t want to open a restaurant if I didn’t have great access to natural meats and fresh produce. To me, that’s why I wanted to cook, not because I want to make money.”

For Yowell, the going hasn’t been easy. After all, she says, “Around here, it’s meat and potatoes or pizza and wings.” Customers have even left SHiFT in an outrage after being told the restaurant didn’t carry Coca-Cola. But she knew there was a need, a niche market for locally sourced, farm-fresh food that, given the bounty of small, family owned farms in western Maryland and Pennsylvania, could thrive with the proper attention.

Her inkling is slowly proving itself. Now, just a few months shy of its two-year anniversary, SHiFT is rolling out annual sales that are almost triple the amount Yowell’s accountants predicted. Yowell likens it to a “little organism that’s growing at its own rate,” but what’s not to like about a bring-your-own-booze policy, bike friendly and open-air atmosphere, and homemade cinnamon rolls the size of your face? Trace a Dish to Its Roots

Trace a Dish to Its Roots

Farm Hand’s Breakfast

Eggs (Savage River Farm and Possibility Farm, Lonaconing, Md.)

Potatoes (Deberry Farm, Backbone Food Farm, and Savage River Farm, Oakland, Md.)

Sausage and bacon (Savage River Farm, Oakland, Md.)

Sourdough toast (Baked in-house from locally milled organic flour from Pennsylvania, cultivated from a 12-year-old sourdough starter out of Accident, Md.)

Loco for Locavore

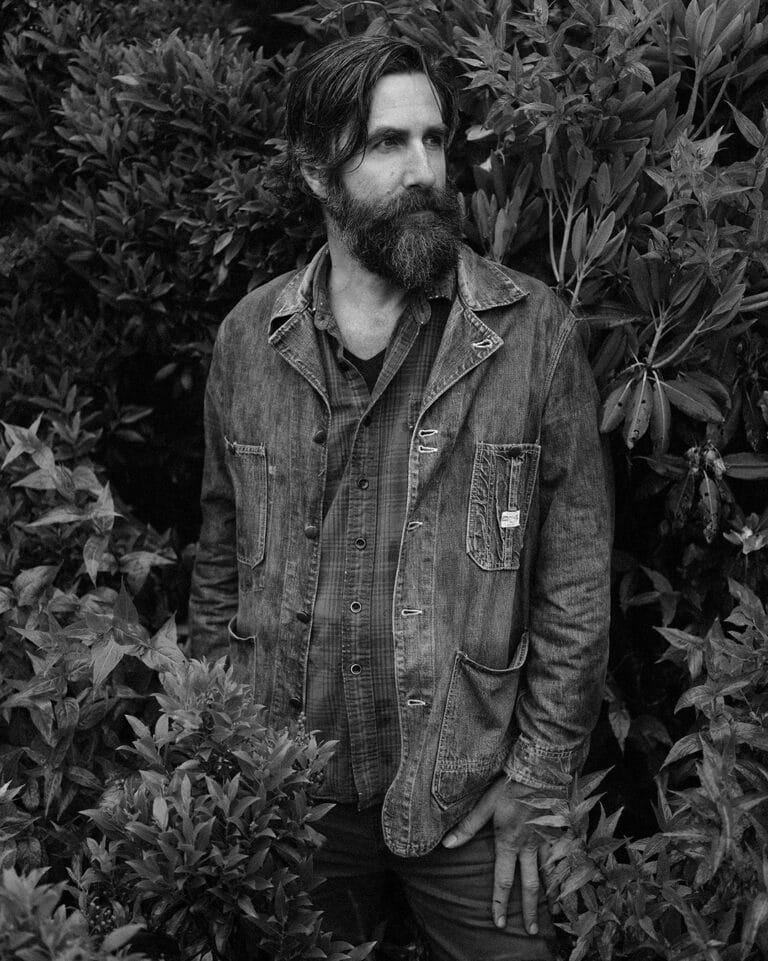

Will Morris has been a longtime supporter of Early Girl Eatery and the local food movement in general. Check out why he loves to eat local!

What is it about Early Girl that captured your loyalty?

I was hooked from the start, as well-prepared southern food is what I grew up on—vegetables, authentic cornbread, biscuits—and real caring for customers and staff as people is a beautiful thing.

What does local mean to you?

To me, it’s about knowing and having a relationship with the owner and the employees and getting better quality.

Why do you support local?

Local restaurants are unique and offer a personal relationship experience, whereas, a chain has all the soul mechanically removed from the experience, replaced with a calculated business model. Not satisfying.

What do you look for as a customer when you go to a restaurant?

I want the food to be well prepared, taste great, and be presented as if the cooks care about their work and care about the customer. You know, when we eat in a restaurant, it’s not just about trading money for food—it’s a human connection and interaction, almost like a family meal. We are feeding our souls as much as our bodies. It’s about the whole experience. Restaurateurs who don’t get this don’t get my business.

Favorite local digs?

Early Girl Eatery for informal and Rhubarb for fancy.

From Field to Fork

Meet Walter Harrill, owner of Imladris Farm in Fairview, N.C. Walter supplies what he calls “most of the good breakfast joints” around Asheville with his locally sourced and produced jams and jellies, and sells his products at more than 60 area grocery stores and tailgate markets.

How did Imladris Farm get its start?

My grandfather, who planted the first commercial you-pick orchard in western North Carolina back in the ‘50s.

Are all of your berries and fruits grown onsite?

We contract with other local growers to keep up. We’ve realized we have an opportunity to support other farmers in a bigger way, so it’s all locally grown fruit but not all of it will be found here.

Why do you source locally? What’s the advantage to a model like this?

Rather than me try to put up 8,000 pounds of raspberries for the season, I’ll put up a few thousand, Larry down the road puts up several thousand, and so on. Between several of us, we find the ability to put up all we need and we diversify risk because in farming, there is a significant chance that whatever crop you’re growing, one year out of five or even three, you may very well

lose it.

What’s in it for the grower?

It’s very easy for the same dollar to circle multiple times through this community. If you spent $10 with John Stehling [at Early Girl Eatery] who then turns around and spends a portion of that money with me, who then turns around and spends that money on one of the local growers, that’s just a lot more powerful than spending money with a company who sends that money to California.

Did you grow up on locally minded, homemade food?

Absolutely not. My mom and dad were the first of their families to leave the farm and get a college education and with that came adoption of the modern diet. I grew up on Chef Boyardee and Ragú. I had to get back here [to the farm] and get my hands in the dirt before I was able to see the advantages of eating the way we eat today.

What in particular is unique about the food movement in Asheville?

As a customer, what’s so great about it is its diversity, the fact that I can sit down at a good local restaurant and have localy grown meat, beef, pork, lamb. I can have local mushrooms, local vegetables, all sorts of good local processed foods like jams and jellies and Green River pickles. There are so many different things that are featured here. It’s not just a matter of local corn and local pork chops. There’s a wide variety of stuff out there, down to the bouquets of flowers on the table.

What do you want our readers, and your customers, to know about the farmers’ perspective?

It’s all about y’all. We’re doing this because this is what you asked for. As important as it is to have chefs that are open to bringing in local produce and as important as it is to have farms to supply that produce, it’s about the consumer. I grew up here in the 1980s when there was no local food movement and there was no possibility. The opportunity to do this now in the environment we have is both extremely appreciated by those of us supplying the industry and also quite simply a factor of your individual choices as customers.

Local Diggs Near You!

Check out these 25 other farm fresh restaurants in the Southeast and Mid-Atlantic!

Horn O Plenty (Bedford, Penn.)

myhornoplenty.com

Bluegrass Kitchen (Charleston, W.Va.)

bluegrasswv.com

Panorama at the Peak (Berkeley Springs, W.Va.)

Stardust Café (Lewisburg, W.Va.)

stardustcafewv.com

The Riverside Hotel (Friendsville, Md.)

riversidehotel.us

MoonShadow Café (Accident, Md.)

moonshadowcafe.com

Woodberry Kitchen (Baltimore, Md.)

woodberrykitchen.com

The Local (Charlottesville, Va.)

thelocal-cville.com

The Red Hen (Lexington, Va.)

redhenlex.com

Little Grill Collective (Harrisonburg, Va.)

Capitol Grille (Nashville, Tenn.)

capitolgrillenashville.com

The Farm House (Nashville, Tenn.)

Blackberry Farm’s The Barn (Walland, Tenn.) americanfarmtotable.com/blackberry_farm

The Market Place (Asheville, N.C.)

marketplace-restaurant.com

The Blackbird (Asheville, N.C.)

theblackbirdrestaurant.com

Sunny Point Café (Asheville, N.C.)

sunnypointcafe.com

Hob Nob Farm Cafe (Boone, N.C.)

hobnobfarmcafe.com

The Mast Farm Inn (Banner Elk, N.C.)

themastfarminn.com

Swamp Rabbit Cafe & Grocery (Greenville, S.C.)

FIG (Charleston, S.C.)

eatatfig.com

ROOST Restaurant (Greenville, S.C.)

roostrestaurant.com

5 & 10 (Athens, Ga.)

fiveandten.com

Frog Hollow Tavern (Augusta, Ga.)

froghollowtavern.com

Fortify Kitchen and Bar (Clayton, Ga.)

fortifyclayton.com

Harvest on Main (Blue Ridge, Ga.)

harvestonmain.com