Unsolved mysteries fascinate because of their mix of true crime and ambiguity, which creates endless opportunity for speculation and armchair sleuthing.

Unsolved mysteries that occur on public wildlands carry an extra wrinkle, as they take place on lands where we play. It’s an eerie feeling to pass a spot that once was the site of a violent crime.

Statistically, crime in public wildlands is relatively rare. Most crime there tends to be vandalism or illegal dumping. As is the case with crime generally, violent crime on public lands tends to be domestic, occurring between people who know each other.

The chance of being assaulted in a national park is one in 1 million. According to the FBI Uniform Crime Report, the average chance of being assaulted in the country at large is 3,100 times higher.

Still, attacks sometimes occur for no discernable reason. Federal agencies recommend using caution and common sense, especially if you are alone.

At least three out of the four cases profiled here involve foul play, and investigators still are pursuing leads even decades later.

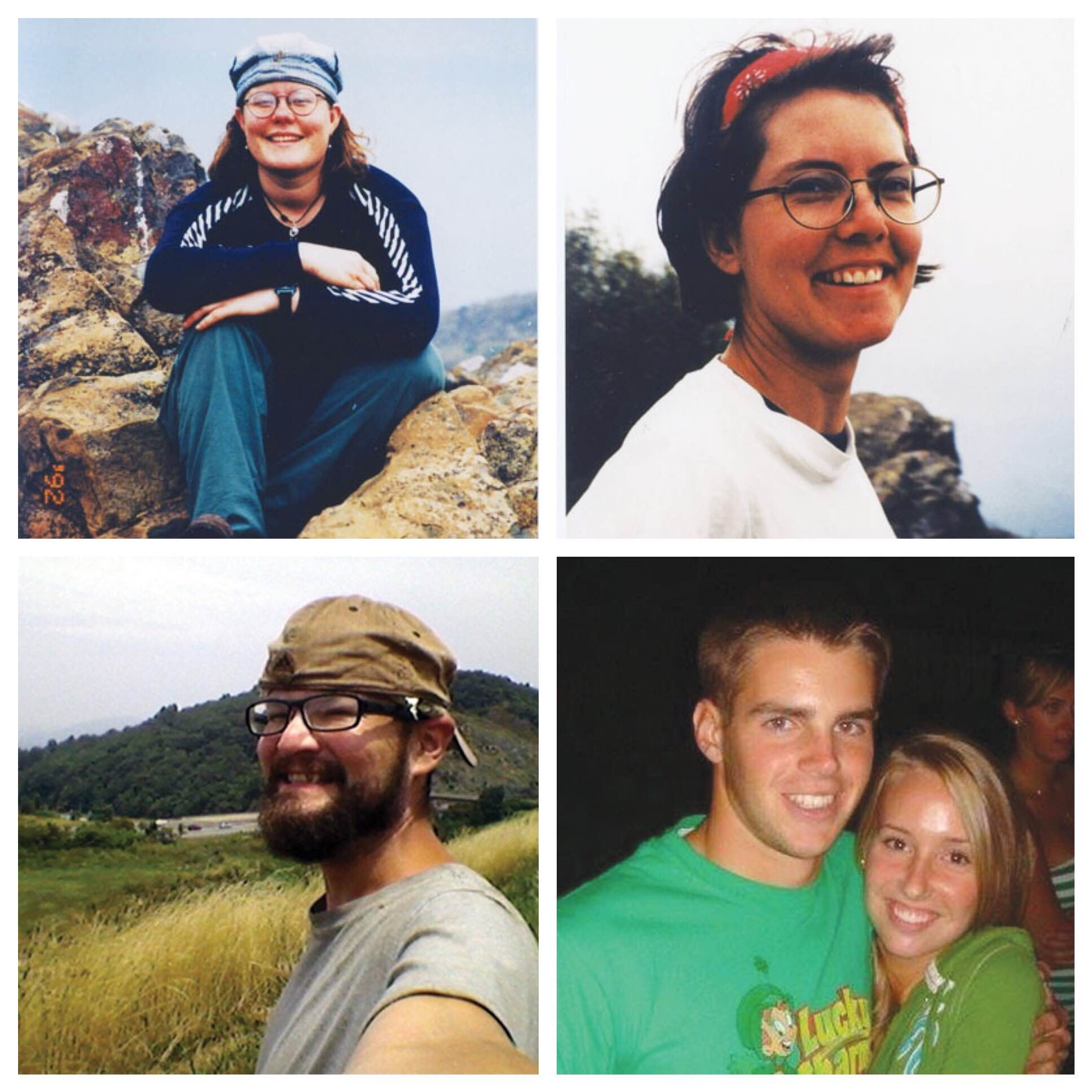

Julianne Marie Williams and Laura “Lollie” Winans

Shenandoah National Park, 1996

The murders of Julianne Marie Williams and Laura “Lollie” Winans 20 years ago in Shenandoah National Park remain unsolved today, though at one point federal officials thought they had their man.

Williams and Winan, 20-something New Englanders arrived at the park on May 19 with plans to stay through Memorial Day weekend. They were noticed missing after failing to show up for work on May 28, and on June 1, the two were found at their secluded campsite, which faced the eastern face of Stony Man Mountain, with duct tape binding their wrists and covering their mouths. Both women were nude with their throats cut. Neither had evidently been sexually assaulted and the only items that seemed to be missing were Williams’ personal belongings, including a journal and her driver’s license. The case generated a huge amount of publicity and tips from the public, but no leads.

A year later, Darrell David Rice was arrested, convicted and sentenced to 11 years in federal prison for stalking and assaulting a woman bicycling on Skyline Drive. Federal officials identified him on cameras entering and leaving Shenandoah National Park around the time Williams and Winans were murdered. On the testimony of a fellow inmate who played in a prison band with Rice and said he’d spoken of killing a woman in the park, Rice was indicted in 2002.

Federal prosecutors dropped all charges two years later, however, based on holes in their case. One potential witness, for example, said he and his wife had been camping in the park around the time of the killings. He noticed a creepy man staring at him across a clearing, and later chose a photo of Rice out of a line-up, but said he was only 65 to 70 percent sure of the identification. The camper’s wife said she’d heard screams the night before; she also said she had then astrally projected out of her body to explore the crime scene.

The biggest blow was DNA testing from a male hair found on the duct tape used to bind the women. It did not match Rice. Still, U.S. Attorney Thomas Bondurant said he still considered Rice a suspect.

This summer, the F.B.I. renewed calls for assistance in solving the murders of Williams and Winans. Rice was released from prison in 2007, then did two more stints for parole violations. In 2014, police in Durango, Colorado, asked for calm after reports that Rice had been spotted in the area sparked a flurry of social media activity and calls to area law enforcement agencies.

Police Chief Jim Spratlen told the Durango Herald, “We have to just realize that he has the freedom to walk about the area. He has the freedom to get a job here, have a house and everything else…All I know is he’s not wanted, and we ain’t looking for him.”

Meanwhile, back in Virginia, the deaths of Williams and Winans are considered an ongoing, active investigation, according to Dee Rybiski, public affairs and outreach specialist for the FBI’s Richmond division. Indeed, in early June the FBI marked the 20th anniversary by issuing a renewed call for tips about the killings.

Anyone with information about Williams’ and Winans’ deaths should contact the F.B.I.’s Richmond office at 804-261-1044 or go to tips.fbi.gov.

Scott Lilly

Appalachian Trail, 2011

Scott Lilly set out to hike the Appalachian Trail from Maryland to Georgia as a way to find himself, but his journey ended in northwest Amherst County, Virginia.

Lilly’s last contact with the world had been at the end of July 2011, when he was climbing the Priest, a landmark mountain in Nelson County. In August, a group of weekend hikers discovered Lilly’s body in a shallow grave just off the trail near Cow Camp Gap, in the Mount Pleasant National Scenic Area of George Washington National Forest. His gear, including his shoes and backpack, was nowhere to be found.

A medical examiner ruled that Lilly, who was from South Bend, Indiana, and used the trail name “Stonewall,” had died of “asphyxia by suffocation,” and ruled it a homicide. Family and friends said that Lilly, 30, was a Civil War enthusiast, thus his trail name’s reference to Confederate Gen. Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson, and that he had set out on the trail as a journey of self-discovery.

In the days following the discovery of his body, the FBI—investigating his death because it occurred on public lands—sought to contact a number of other hikers thought to have had contact with Lilly, including “Mr. Coffee”, “White Wolf”, “Papa Smurf”, “Combat Gizmo” and “Space Cadet.”

True-crime and Appalachian Trail online forums buzzed with rumors and speculations about Lilly and the hikers identified by the FBI, but five years later, no arrests have been made.

Anyone with information about Lilly’s death should contact the F.B.I.’s Richmond office at 804-261-1044 or go to tips.fbi.gov.

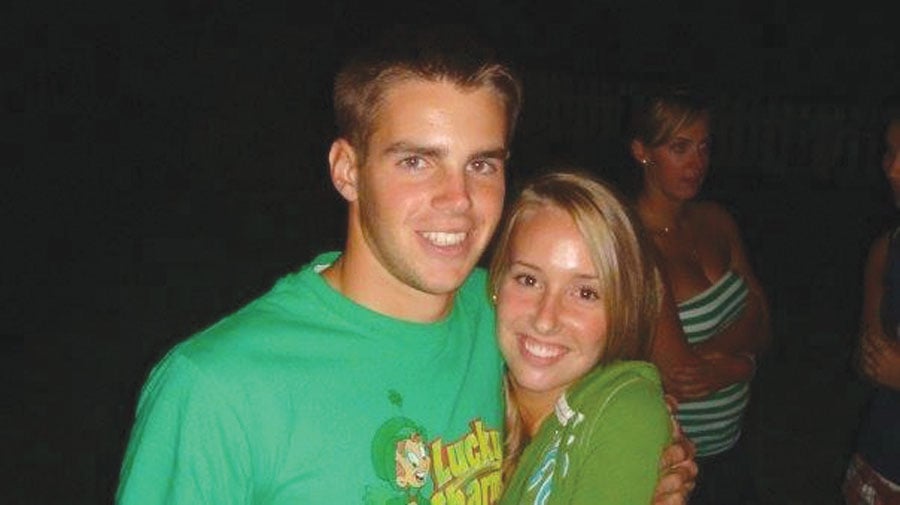

Heidi Childs and David Metzler

Caldwell Fields, 2009

Heidi Childs and David Metzler had spent four years together, but as rising college sophomores just a couple of days into the 2009 fall semester, they still had their whole lives ahead of them.

On the evening of August 26, they got into Metzler’s 1992 Toyota Camry and drove out Craig Creek Road to talk and play guitar at Caldwell Fields, a recreation site in Jefferson National Forest. Ridges rise on each side to form a narrow valley around the site, which is home to three mowed fields, large shade trees and a stocked trout stream.

The next morning, a man walking his dog down the road found their bodies—Metzler in the car and Childs outside. They had been shot with a .30-30 rifle sometime between 8:25 p.m. and 10 p.m., according to authorities. At a news conference soon after the bodies were found, the Montgomery County sheriff called the killings “brutal and ugly.”

Since then, a coalition of local, state and federal law enforcement agencies have investigated the case, offering a reward of $70,000 for information leading to an arrest. In 2012, officials released new information: That Childs’ purse, which included her cell phone and credit card, had been taken from the scene, and that investigators had recovered DNA evidence, which was tested against nearby residents.

Seven years after the homicides, however, no arrest has been made. However, “this is not a cold case,” said Lt. Kenny Light in August. “This is still a very active investigation, to the point that when you called, I was writing up something on this case.”

Montgomery County law enforcement officials request anyone with information about the crime to contact them. They’re looking for information on people or vehicles that may have been in the area that night.

Contact Light at 540-382-6915, ext. 44422 or [email protected].

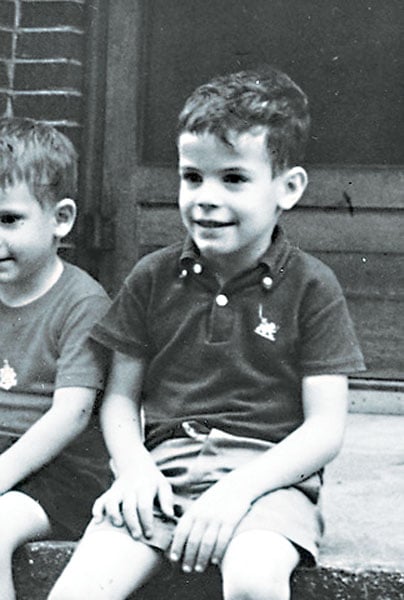

Dennis Martin

Great Smoky Mountains National Park, 1969

The sudden disappearance of 6-year-old Dennis Martin on June 14, 1969, sparked the largest search-and-rescue operation in the history of Great Smoky Mountains National Park. The ultimate failure of that effort left a nearly 50-year-old mystery that still haunts many hikers and parents visiting the park today.

Dennis was part of a multi-generational overnight hike into the Smokies that spent its first night in Russell Field before moving on to meet more family the next day at Spence Field. Around 3 p.m., Dennis and three of the other Martin children decided to set off into the woods but circle back around to surprise the grown-ups. Three of the kids went one way, and Dennis went another.

That was the last time Dennis was seen.

When he didn’t show up with the others, the adults waited a few minutes before going to look for him. That evening, as darkness fell, a storm dumped more than 2 inches of rain on the Smokies, setting a wet weather pattern that continued into the following days as the search expanded. Over the next week, hundreds of people descended on the park to help in the effort, growing to a peak of 1,400 a week after Dennis had disappeared. The searchers included volunteers of all ages, law enforcement and public safety personnel, and even 60 Green Berets.

But Dennis disappeared in rugged terrain, covered in rhododendron and mountain laurel, with roaring creeks obscuring sound, which hampered searchers’ efforts. Park officials later produced a report blaming the search’s failure in part on the fact that the arrival of volunteers outpaced the organization, resulting in confusion and the possibility that searchers had destroyed evidence that might have helped locate Dennis.

What happened to Dennis? No one knows, although a range of anecdotes that emerged after the search offer a range of possibilities.

A little more than 3 miles from Spence Field, some searchers found the footprint of a shoe that would have fit Dennis. However, it was initially dismissed as the footprint of a searcher and wasn’t pursued. Another man reported hearing screams and noticing a ragged man he initially mistook for a bear. Because this sighting occurred 9 miles from Spence Field, it too was initially dismissed. Finally, a ginseng hunter said he found the bones of a small child, but didn’t report them because he had been poaching the medicinal plant. When he finally did report the bones years later, they could not be found.

Most people believe that Dennis either died on his own, was attacked by a predatory animal or was abducted by a person. Nearly 50 years later, no one knows for sure—and it’s increasingly unlikely that anyone ever will.