In 1924, canoeist Bill Havens had a choice: compete in the Olympics or witness the birth of his child. Bill chose the latter, and 28 years later, that child, Frank Havens, brought the gold medal home from the 1952 Olympics in Helsinki. Today, the Havens family is still on the water, including the now 92-year-old Olympic medalist Frank.

Georgetown, Maryland. 1924.

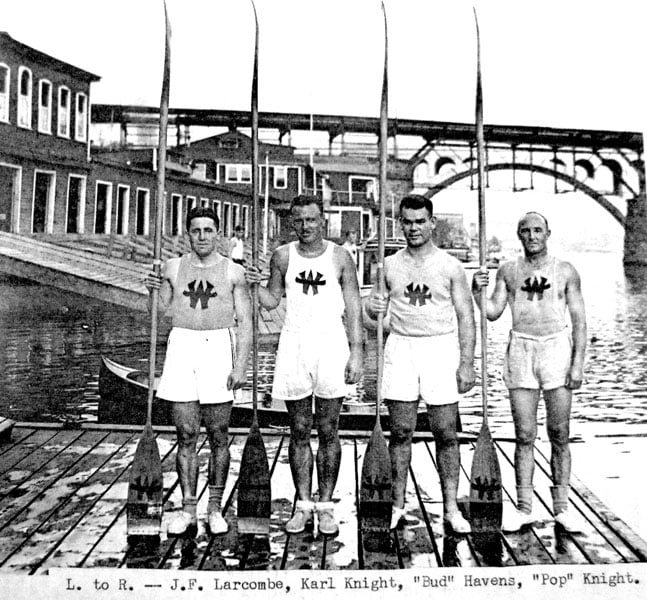

Brothers Bill and Bud Havens, former Mid-Atlantic wrestling champions, are standing at the threshold of a very different athletic benchmark: becoming the first canoeists to represent the United States in Paris at the Summer Olympics.

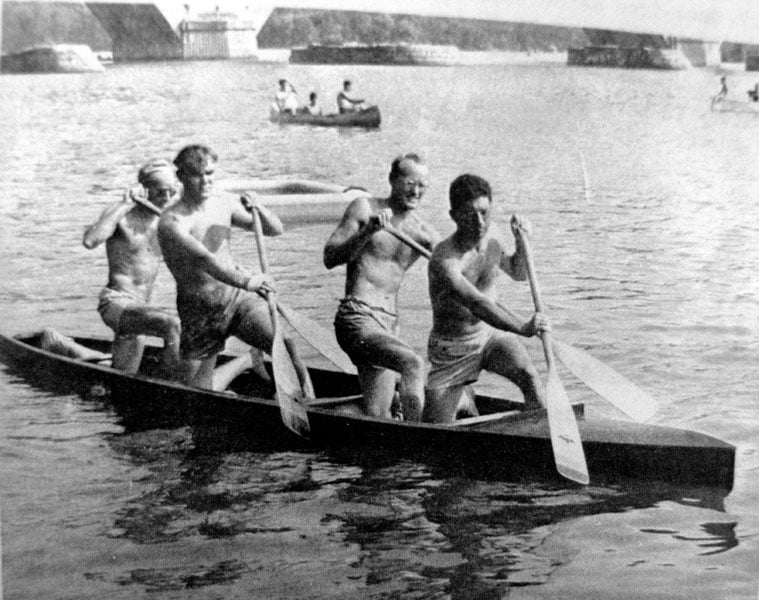

It’s the first year canoe sprint has ever been an event at the Olympics. Bill, 27, and Bud, 21, compete against 20 other paddlers in the Olympic Trials to earn their place on a four-man canoe crew. For months, the brothers train day and night on the Potomac River with the Washington Canoe Club, preparing their physical and mental fortitude for the games. Bill, undefeated in both the one-man single and double blade events, has high hopes of bringing home the gold.

But just weeks before the team is set to sail for Paris, Bill is forced to face reality—his expecting wife is due sometime in late July, the exact time at which Bill will be competing on the other side of the globe. The decision, though not easy, is obvious. Bill forfeits his spot on the team, and just four days after the games (at which Bud Havens and the rest of the U.S. canoe crew win three gold, one silver, and two bronze over six events), his son Frank came into the world.

Bill never made it to the Olympics, though he continued to compete with his brother close to home. However, his sons Bill “Junior” and Frank, did. After serving in the Army Air Corps during World War II, the second generation of brothers qualified for the 1948 Olympics in London. Junior, largely considered the better paddler of the two, placed fifth in the solo 1,000-meter canoe race. Frank, surprising even himself, came home with a silver medal in the solo 10,000-meter event.

Buoyed by their 1948 Olympic success, the brothers moved in together in Vienna, Va., to train for the 1952 games. Their coach was none other than their father Bill. Junior and Frank spent the better part of the ensuing four years on the water, training to compete together as a tandem canoe team.

“Even in practice they were beating the world record,” says Dodge Havens, one of Junior’s three sons. “It was pretty much guaranteed they were going to get a gold.”

But Olympic disappointment struck again during the winter of 1951. Junior, who worked as a schoolteacher off the water, was helping a colleague move a car that had been buried by snow when he lacerated the tendons in one of his hands. In a matter of minutes, his chance for Olympic glory was gone.

Frank, as his Uncle Bud had done 28 years prior, departed for the 1952 games in Helsinki without his brother Junior. With a time of 57:41, Frank set the new world record and took home the gold in the solo 10,000-meter event. In a telegraph addressed to his father after the games, Frank said, “Dear Dad, thanks for waiting around for me to get born in 1924. I’m coming home with the gold medal you should have won. Your loving son, Frank.”

“Dear Dad, thanks for waiting around for me to get born in 1924. I’m coming home with the gold medal you should have won. Your loving son, Frank.”

Frank competed in the Olympic masters division in 1956 in Melbourne and 1960 in Rome, but he never podiumed again. To date, Frank is the only American canoeist to win gold in a solo single blade event. Like their father and uncle, Frank and Junior continued to compete well into their 60s. The brothers, who preferred to race as a tandem team, regularly crushed the competition on both the national and international stages.

“He was never bitter about it,” Dodge says about his father’s unfortunate mishap before the ’52 Olympics. “He was very proud of his younger brother’s success. They loved to race together in tandem events. They were pretty much unbeatable. Even when they were in their 60s and 70s, they’d high kneel [the traditional stance for canoeing] and beat everybody’s butts, even the 25-year-olds.”

Between 1936 and 1953, Junior won 19 National Canoe Tilting Championships. Frank went on to be a six-time National Paddling Single Blade Champion. In 1985, at the age of 61, he competed in seven different events at the World Masters Games in Toronto and won every single one. In 1995, Frank was inducted into the Virginia Sports Hall of Fame, a testament to his storied past and countless accomplishments.

Frank, now age 92, is still on the water nearly every day. Though he last competed in his late ’80s with his son Dan, he’s proud to see that the spirit of the river has been passed down from generation to generation. Dan, age 65, and his son Sean have continued the tradition of training with the Washington Canoe Club. They both compete in the growing East Coast outrigger racing scene and regularly place in the top three.

Junior’s sons Dodge, Keith, and Kirk are also accomplished paddlers and hold multiple Whitewater Open Canoe Downriver National Championships. All three competed in the Olympic Trials for the 1980 and 1984 Olympics, but didn’t make the cut. Keith’s sons Zane and Zaak also join their father and uncles among the nation’s top canoeists and have been competing and winning National Championships since the age of 10. Zane has been serving off and on for the past year as a crewmember aboard the Hōkūle‘a, a Polynesian voyaging canoe that has been circumnavigating the world.

“I don’t know whether it’s in our blood or in the culture,” says Dodge, but according to Frank, being a Havens family member is synonymous with being a canoeist. You can’t be one without the other.

Q+A WITH FRANK HAVENS

What’s your earliest memory of being on the water?

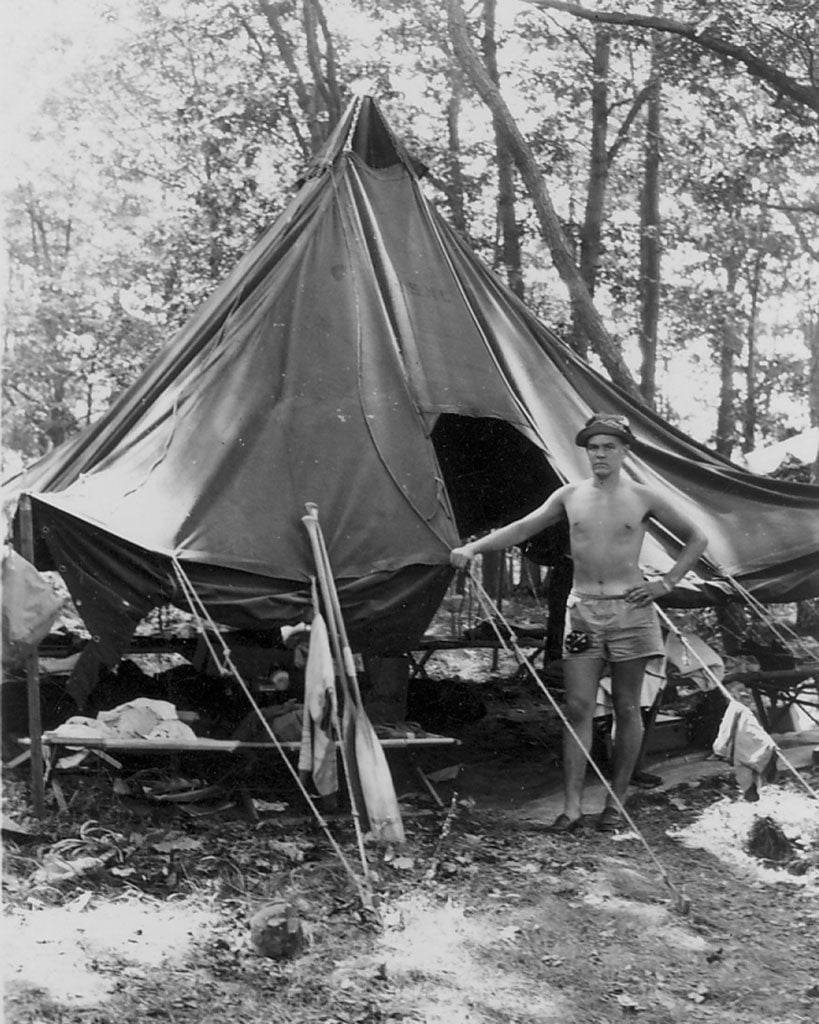

FH: We were all brought up on the Potomac River. We had a camp on the river and my grandfather built this place. There was a huge room where we could congregate and have meals and stuff. I can’t remember when I couldn’t swim, so I guess somebody must have taught me early.

What was your relationship like with your brother, Junior?

As a young kid, Bill [Junior] being five years older, I used to follow him around like a puppy. He was the man. In high school he was Mr. Everything. He had such a reputation. He was phenomenal at everything he did. My aim at that time was to be as good as my brother Bill was. My brother was my main competition for a long time, especially in training. Early on, Junior was the best that was around. Having him out there to push me, I’m sure I got a lot better because he was around. I didn’t get to the point where I could whip him until we were both Olympic caliber.

How did you end up with the solo 10,000-meter as your signature event?

My dad recognized early that Bill Junior used to push me hard in the 1,000-meter, but as I progressed, he recognized I had the capacity to do longer distances. I was always pretty good in staying with it and being able to get into a rhythm that would move the boat. I did better the longer the race was. It just came naturally.

Do you remember what it was like when you arrived in London for the ’48 games?

We went to London on a boat from New York and came in at Southampton. When we got there, the Germans had been bombing Britain all during the war, so Southampton still had burned out buildings there on the waterfront. London was still a mess. They put us [the athletes] in an evacuees’ camp. We were over there for six weeks. That’s where it all started. I started to come into my own a bit at those games.

After the ’48 Olympics, you and your brother decide to train together for the ’52 games in Helsinki. What was that like?

We moved in together, bought a house out in Vienna, and really hit it hard for four years. He was a schoolteacher in Arlington and I worked for an appraisal company. We would train early in the morning and after work, two workouts a day in the Olympic years. I can remember paddling the Potomac when it was pitch dark but we knew that river like the back of our hand so we never had any trouble with it. Our dad was our coach and he pushed you hard.

When Junior injured his hand and had to give up his chance to go to the Olympics, you kept going. In what way did your brother still help you prepare for the games?

We had planned to go to Helsinki as a tandem. We had trained tandem so long that I think I was able to increase my stroke rate which doesn’t sound like much but it takes some doing when you’re already paddling somewhere in the high 50s strokes-per-minute. To pick it up was something else.

What is one thing you remember about your father and coach, Bill?

High kneeling, it’s all about getting the blade in the water as far forward as you can and getting at it from your hip. It’s a rotation of your upper body from the butt up. My dad always said, “If you didn’t have such a big butt, you wouldn’t be as good as you are.”

How did you feel going into the games? Nervous? Excited?

I was always in Bill Junior’s shadow, like all my life. Up until ’48, I had never done anything that was “outstanding.” When I won the Olympic trials that year, that’s when everything changed for me. The girl I was really interested in decided I was finally a keeper. Everything seemed to start working out then.

Walk me through the day of the race, from the start to the finish line.

I was behind at first. I didn’t have a great start. In the finals there were a dozen competitors. I think I was probably in the first five out there. I remember passing the German, mainly because he made a grunt when I went by. And then all that was in front of me was the Czech and the Hungarian. I could see they were riding each other’s wake a little bit. Every time we’d come to a turn, they would come as close to the buoy as you can. Really they were kinda blocking me out on the turns, but I was still in the top three, so as long as I hung in there I knew I could possibly catch them if I had anything left. When we came to the final turn, they let a little gap out while they were changing positions. I put the bow of my boat right in that gap and gave it just about all I could. When we came out of that turn and headed into the last 1,500 meters I was probably a deck’s length ahead of them. I could see them in my peripheral vision. I knew they were right there. I think I only won by 12 seconds.

Not only did you win that year but you also set a new world record. What did that accomplishment feel like?

I was completely exhausted after this one. My teammate picked me up and handed me a flag and carried me around on his shoulders. It was quite an ending to a day. If it hadn’t been for a squeaky pully at the podium, I’d have cried, but when they were raising the flag, the damn pully was squeaking so it got my attention. That thing should have been lubricated.

How soon were you back on the water after the ’52 Olympics?

I had a day or two off, then I had to go back to work. I raced the Nationals in Philadelphia the next weekend.

How has the sport of canoeing changed since you first started paddling?

The single blade boat that I raced in at Helsinki, you never see any of those anymore in world competition. They have a boat now that is so narrow, I don’t know if I could get my knee in it. We paddled 17-footers that weighed about 47 pounds, something like that. Pushing [a canoe] for an hour on one knee, well, we did it so many times it was just routine. But the boat I raced in Helsinki would not be comparable to anything they race today.

You and your brother continued to race for many decades after the Olympics. What were some of your favorite races?

We raced the Canadian Masters for years and the World Masters. We really kicked butt in the World Masters after we were no longer Olympic-type paddlers. Of course, you’re paddling in age groups, so it got awful easy when you only had people within five years of your age to compete against. We went to Denmark and Sweden. We took a crew to Hong Kong, did an awful lot of paddling around the world. It was quite a life we had.

Do you still paddle today?

I hate to admit it, but I sit and do it now. I had a knee operation several years ago. I’m paddling a regular canoe. It’s a beast but I know I won’t have any problem staying in it. I’m not going today because it’s pretty damn cold, but I’m on the water most every day.