Cumberland Island is a beloved national seashore and a global biosphere reserve along the coast of Georgia. Over 60,000 hikers and campers visit the island each year. But if a proposed spaceport is built directly across from the island, the national seashore could be closed to visitors for weeks at a time, several times a year.

Camden County, Georgia, home of Cumberland Island National Seashore, has spent millions in planning and promoting the proposed spaceport, with the goal of luring private spaceflight companies to the area.

Conservation organizations and property owners in the area have been adamantly opposed to the project for years. The launch site is located dangerously close to Cumberland Island and hundreds of private landowners, but Camden County continues to pour money and resources into it, hiring a public relations firm and promising jobs and an economic boon for the area.

“Georgia has now officially entered into an elite group of space states,” said Georgia Representative Jason Spencer (R-Woodbine) in a written statement. “Commercial space companies will see this as a major development and will start heavily considering Georgia’s aerospace assets and create high paying jobs for our citizens.”

A Recently Released Draft

The Draft Environmental Impact Statement, paid for by Camden County and written by private firm Leidos, proposes that the county move forward with the project. The document suggests any adverse impacts are “short term and temporary” and therefore not “significant” enough to derail the project.

However, the Draft Environmental Impact Statement does not address potential impacts in the case of an explosion, or launch failure, among other apparent missteps, leading many environmentalists and concerned citizens to question the validity of not only the environmental review, but the entire project.

“The Environmental Impact Statement is an incomplete document,” said Megan Desrosiers, Director of Brunswick-based environmental group One Hundred Miles. “You cannot assess the costs and the benefits of this project without truly understanding the risks associated with that type of land use in that location.”

‘THE WORST POSSIBLE SITE’

Every other spaceport in the United States launches directly over the ocean. But the proposed Spaceport Camden site would launch over dozens of private residences and a national park that hosts tens of thousands of visitors each year.

It’s also located on a toxic site that has already experienced deadly explosions. Morton Thiokol, Inc. manufactured booster rockets on the site for NASA, including the space shuttle Challenger in the 1980s. Those Thiokol-built rockets failed, and caused the infamous shuttle to explode just 73 seconds into flight in 1986. Fifteen years earlier, Thiokol was involved in another tragedy in Camden County on the banks of Todd Creek.

Also on the chosen Spaceport Camden site, a fire started where 60 people were assembling magnesium flares. The fire reached a storeroom where four tons of magnesium and sodium nitrate were kept. The resulting explosion killed 29 and injured 50, with shock waves shattering windows up to 11 miles away. The explosion was heard as far away as Jacksonville, Fla., according to a 1986 New York Times article comparing the two Thiokol-related disasters.

Years later, Union Carbide produced highly toxic methyl isocyanate gas on the site. The gas is famous for a 1984 tragedy in Bhopal, India, where it spilled at the city’s Union Carbide plant and was eventually held responsible for more than 3,500 deaths.

Camden County spent $960,000 for a two-year option to purchase the site, allowing the environmental review process to take place. If Spaceport Camden gets licensed for spaceport activities, the county will pay a total of $4.8 million for the property.

“It’s the worst possible site for a commercial spaceport,” said Kevin Lang, whose family owns property on Little Cumberland Island. “It endangers people, wildlife, property, and public lands.”

The site is bordered by Todd Creek to the north, a tributary of the nearby Satilla River, and intracoastal marshland to the east.

One slice of property not included in the potential sale is a 56-acre Superfund hazardous industrial waste landfill on the border of Todd Creek. Union Carbide is required to clean up that tract before it can sell it. Cleanup is estimated to cost $500 million, so it is not included in this sale.

With all of this contamination on a site surrounded by water, environmentalists worry the construction and rocket launches will cause severe water contamination.

“We have no idea,” Desrosiers said about the impact the site’s contamination could have on nearby waterways.

“There have been no studies on vibrations, extreme heat, fuel spills, and other potential impacts that happen regularly at rocket launch facilities. How will construction affect the existing contamination on that site? None of these concerns are addressed in the Environmental Impact Statement, and Camden County isn’t talking about them. These are huge concerns—especially because of the hazardous waste landfill that is on the site now, that sits right on the bank of Todd Creek. And that bank is eroding. And so with vibrations, and continued disruption, thanks to the spaceport, that site will continue to get worse over time.”

EXPLOSIONS EVERY TWO YEARS

The FAA typically defines a “blast zone”, or area within full impact zone of a rocket launch as a two-mile radius around a launch pad. The hazardous waste landfill is 1,000 feet from the bank of Todd Creek, and 1.6 miles from the proposed launch pad. The Satilla River channel is 1.2 miles from the launch pad.

According to the Environmental Impact Statement, a launch pad has to be 10,600 feet away from any boundary on the site. At the Spaceport Camden site, 10,600 feet stretches well into the marsh.

“What they’re doing is they’re assuming the public waters are basically okay for them to have an explosion in,” Desrosiers said. But rockets at Spaceport Camden would launch over state waters, not offshore federal waters, like at most other spaceports, such as Cape Canaveral in Florida or Wallops in Virginia. Plus, this spaceport is for private companies to launch.

The Environmental Impact Statement puts the failure rate of rockets at 2.5 to 6 percent, including at launch and any potential planned on-site landings. That means there would likely be one to three explosions of rockets every two years.

“If the explosion happens on the pad or just after launch, which is when most of them happen, it will definitely affect the marsh. The fuel spills that occur, the debris, the shrapnel, anything that comes off the rocket is going directly into the marsh and the Satilla River,” she said.

Despite the treatment of the marsh as “undeveloped buffer,” any fuel spill or debris would affect the slow-moving marsh to a much higher degree than the ocean.

“The marsh will hang on to the contamination a lot longer than the beach, for example. The other thing is the marsh tends to be the nursery ground for a lot of shellfish and marine mammals and those babies and younger organisms are the most vulnerable, which is why they are born in the marsh and not the ocean. So to have the type of contamination that could potentially occur here affecting the most vulnerable species in the food chain, it’s just a bad recipe for disaster,” Desrosiers said.

LOOK OUT BELOW

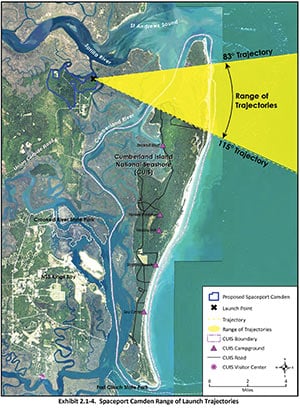

Typically, spaceports have downrange hazard or exclusion areas that vary in width from 12 miles to 25 miles extending offshore. By law, these areas must be clear of people during a launch in order to achieve the FAA-mandated casualty expectation of one in one-million per launch. The draft Environmental Impact Statement for Spaceport Camden includes diagrams that indicate only a 5-mile-wide hazard or exclusion corridor.

And Camden County is seeking to skirt the FAA law by deeming all residents, hikers, and campers within the hazard zone as “authorized persons”. This seems to be an attempt to eliminate the need for evacuation, which is problematic because of a Georgia state law prohibiting forced evacuation of private property owners from their homes for the benefit of private industry.

What this means is that visitors to Cumberland Island National Seashore would unknowingly be deemed authorized persons for a private spaceport, and their lives could be threatened by any explosions that occur over the island.

Cumberland Island and Little Cumberland Island also have hundreds of residents who would unwittingly be jeopardized by every rocket launch.

Jim Renner, a Little Cumberland Island property owner and a geologist who has worked in environmental permitting for a wide range of municipal and industrial projects, wrote to the FAA requesting an explanation of why he and his family would be considered “authorized personnel” during a launch.

FAA Environmental Specialist Stacey Zee responded via email, saying authorized personnel was not an FAA term. According to Zee, “A launch operator could not conduct a licensed launch from Camden if the risk to any member of the public, including those who remain on Cumberland Island and Little Cumberland Island, did not meet this requirement. A launch operator who intends to conduct launches from Camden may need to identify closure areas to meet this requirement.”

Some are speculating that the term originated from Spaceport Camden project consultant Andrew Nelson. Most recently, Nelson was the Chief Operating Officer of Spaceflight company XCor Aerospace, which filed for bankruptcy in November 2017 . XCor sold millions of dollars’ worth of advance tickets for its space plane, despite never actually having a space plane. XCor promised to create dozens of high paying jobs in its contract with Midland, Texas. The jobs never materialized. The $10 million that Midland paid XCor to relocate there is gone—along with all of the money paid by those who purchased space plane tickets.

Spaceport Camden would launch 12 times a year, with 12 scheduled test launches, which would each normally require evacuation of campers and residents of Cumberland Island and Little Cumberland Island.

Spaceport Camden Project Lead and Camden County manager Steve Howard and representatives for the Federal Aviation Administration did not respond to request for comment.

“Camden County’s Draft Environmental Impact Statement noticeably lacks significant discussion of impacts to residents, private property, commercial fishing, businesses, ecosystems, and visitors to Cumberland Island National Seashore,” said Renner. “It does not critically examine whether multiple closures of land, sea, and air hazard zones will have any negative impacts. What happens if 40,000 pounds of kerosene are dumped into the salt marsh? What if fiery debris lands on Cumberland Island? None of these negative impacts are even considered.”

“Camden County’s draft environmental impact statement is astonishing in its lack of concrete information,” continues Renner. “There are numerous places where conditions and conclusions are asserted without any supporting analysis. There are numerous statements to the effect of, ‘Oh yeah, we need to do a study of that before we start.’ This is the time for those studies!”

The National Park Service has voiced concerns about the spaceport, citing concerns about “closures that will restrict visitor access, impacts to natural resources, and potential threats to visitor safety.” When former Cumberland Island superintendent Fred Boyles was asked what worried him most about the future of Cumberland Island, his answer was clear: the spaceport. “The spaceport is the biggest threat ever to Cumberland Island and all who care about it,” said Boyles.

Many conservation organizations—including the National Parks Conservation Association, 100 Miles, Georgia ForestWatch, Coastal Georgia Audubon Society, and Wild Cumberland—are also opposed to the spaceport and alarmed by Camden County’s environmental impact statement. With so much information missing from the environmental impact statement, local resident Steve Weinkle filed dozens of public records requests to assemble a mass of information about the spaceport at spaceportfacts.org. Weinkle has also spearheaded a grassroots campaign to protect Cumberland Island from the spaceport at protectcumberlandisland.org.

Said Weinkle, “We need for everyone who values this remarkable place to let their voices be heard.”

—The public comment period on the Camden Spaceport has been extended to June 14.