The night sky is more than a pretty backdrop for a camping trip. Dark skies can improve the health of people and the planet.

There are over 400 billion stars in the night sky, but most people living in the South can see fewer than a dozen. Light pollution, the proliferation of bad outdoor lighting, is blotting our view of the galaxy. Currently, two-thirds of Americans can’t see the Milky Way from their backyard.

Light pollution may sound like a frivolous problem compared to climate change or air quality, but the need for dark skies goes beyond wanting to see the stars. The more we learn about light pollution, the more we realize darkness is tied to the overall well-being of humans and our ecosystem. New studies show the prevalence of outdoor lighting could be affecting everything from migratory bird patterns to breast cancer rates.

Dark skies: a cure for cancer?

The stars in the sky are an integral part of our cultural identity. The oldest evidence of astronomical observations are 30,000-year-old cave paintings found in France. The ancient Babylonians created systematic charts of the night sky, keeping detailed records of the paths of planets. The Mayans built observatories. The Polynesians developed an accurate and complex form of celestial navigation that helped them travel over thousands of miles of open water. The Egyptians looked to the constellations as gods. And the star of Bethlehem played a pivotal role in the Bible.

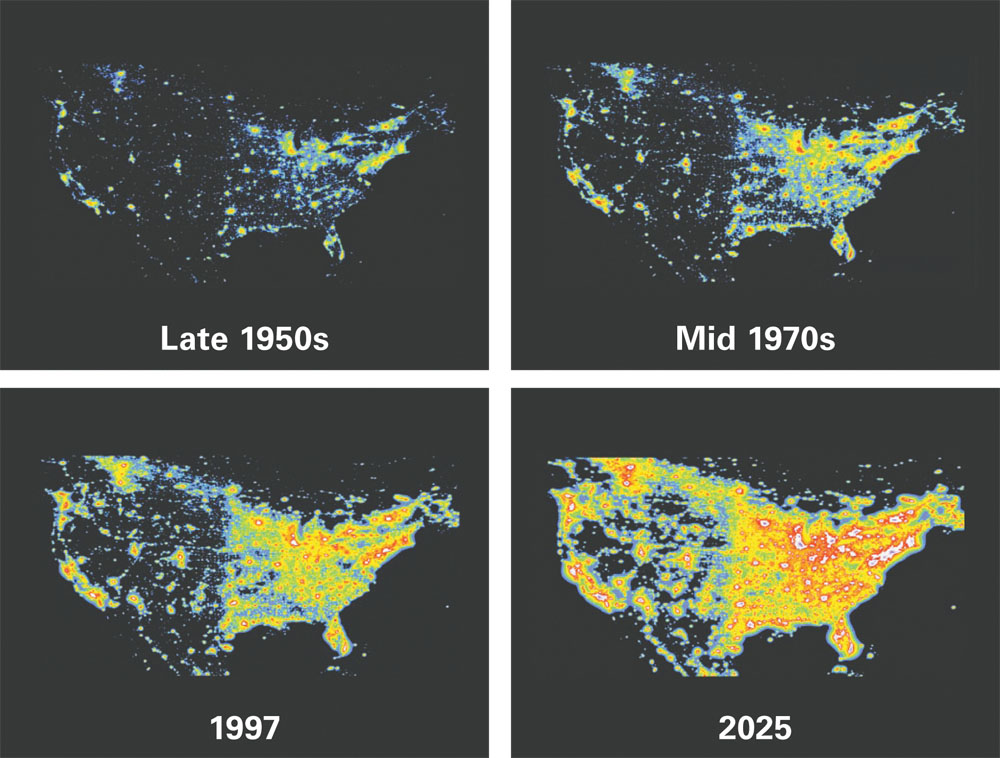

Fascination and reverence for the night sky has been part of every known culture in human history. Yet we may be the last generation to be able to look up and wonder about the night sky with the naked eye. Because of development and the outdoor lighting that comes with it, the U.S. sky is brightening by 5 to 10 percent annually. Almost 99 percent of us live in areas already considered light polluted by astronomers. If the proliferation of outdoor lighting continues as projected, by 2025, there will be few dark skies left in the continental United States.

Parking lot lights, over-lit store fronts, flood lights, gas station canopy lights, highway lights, surface street lights all contribute to sky glow, the shimmering haze above a city that is the by-product of outdoor lighting. Astronomers have been lamenting light pollution for decades, but scientists are just now learning that the potential damage from sky glow and errant light could extend farther than just our obscured view of the stars.

A growing body of research on animal and plant life shows that artificial light can alter behaviors, corrupt foraging areas, and affect breeding cycles and migratory patterns.

The best known problem associated with light pollution concerns sea turtles. Female turtles will avoid nesting on beaches adjacent to lights, and turtle hatchlings have been known to navigate toward beachside artificial light instead of making their way back into the ocean. Every year, over 10,000 birds, disoriented by New York City’s ever-present glow, collide with the city’s skyscrapers during their nighttime migrations. Prolonged exposure to artificial light also prevents some species of trees from adjusting to seasonal variations.

The damage of excessive artificial light extends beyond the wild kingdom. In the last 15 years, ten different peer-reviewed studies on humans, rodents, and monkeys show that artificial light influences hormone secretion, heart rates, sleep propensity, body temperature, even gene expression. In 2009, the American Medical Association (AMA) declared light pollution a health hazard, stating that increasing amount of light is disrupting the population’s circadian rhythm, depressing immune systems, and increasing cancer rates. That’s because exposure to consistently bright lights at night suppresses the synthesis of melatonin, the hormone that prevents cancerous growth formation and development. Women are generally more sensitive than men, and an increase in breast cancer has been seen in female night shift workers whose natural circadian rhythms have been altered by their schedule.

The increasingly popular LED lights might have an even greater impact on humans because of their blue content, which mimics the blue spectrum of light emitted by the sun. According to a Harvard study published in 2003, lights with higher blue content like LEDs suppress melatonin for twice as long as standard lighting.

“The bluer the light, the more impact on the circadian rhythm,” says Bob Parks, executive director of International Dark Sky Association (IDSA). “Basically, blue light resets your body’s clock like sunlight, telling you to be awake.”

IDSA is the only non-profit working to raise awareness of light pollution on the national level. The recent blue light studies are of particular concern because LED lights are becoming ubiquitous across the United States.

“These new LEDs will be the fixture of choice in two to five years,” Parks says. “This influx of blue light could do serious damage to human health and our ecosystems.”

Parks has the daunting task of convincing our federal government that darkness is a natural resource worth protecting like clean air and water. So far, the EPA isn’t buying it, and there’s currently no federal legislation addressing light pollution, and only a handful of states have regulations regarding outdoor lighting.

“This is an issue that falls between the cracks of a lot of different agencies,” Parks says.

IDSA held two congressional briefings on light pollution, which led to 11 house members sending a letter to the EPA requesting a study. The IDSA was also able to convince Congress to address light pollution in their version of the recent energy bill.

The U.S. expends an estimated 17.4 billion kilowatt hours of electricity in wasted light each year. That’s roughly 32 billion barrels of oil down the drain, or for those of us living in Appalachia, nine million tons of coal.

Scared of the dark

Scared of the dark

Getting the American public to address light pollution is an uphill battle, primarily because Americans are scared of the dark.

We’ve been trained to think that more light is safer. Yet a number of studies show that more light can actually mean more auto accidents and more crime. Overhead street lights are installed on highways throughout the country, but according to the U.S. Department of Transportation, only lights at intersections have proven to reduce accidents, while glare from street lights can actually impede a driver’s visibility. The Illinois Criminal Justice Authority studied the effects of lighting high crime areas in downtown Chicago. The city increased the lighting in an eight-square-block area and found that violent crime increased 32 percent under the brighter lights. Vandalism went up 77 percent. Similar results were found at school districts in Washington, California, and Texas. Forced to turn off their outdoor lighting due to budget cuts, school districts in these states found that vandalism decreased significantly during the “no lights” period.

And yet we feel safer in brightly lit areas. The United States has always had a love affair with public lighting. By 1890, just 13 years after the first public light was installed in the world, more than 130,000 public arc lights were in operation in cities across the country. Today there are over 30 million street lights in the U.S., and over 50 percent of that light is wasted because it misses the street altogether.

One group of Americans that isn’t scared of the dark is national park visitors. The National Park Service is the only federal agency that recognizes light pollution as an issue, and has been studying the problem since the mid-1990s.

“Virtually all parks are suffering from light pollution,” says Chad Moore, manager of the NPS Night Sky Team. “You can see Las Vegas from Bryce Canyon National Park, 300 miles away. You can see Phoenix from parts of the Grand Canyon.”

As light from nearby communities begins to encroach on the borders of our national parks, the visitor’s experience is degraded.

“If you can’t see the stars above El Capitan in Yosemite, then you’re missing something,” Moore says.

Moore and his team have gathered light pollution data from 75 park units and are working with rangers to educate the public through interpretive night sky programs, which have become the most popular programs the park service offers.

“There’s always been an appreciation for sleeping beneath the stars,” Moore says. “But the chance to see a dark sky is becoming one of the things people come to appreciate about our parks because it’s so rare elsewhere.”

Dark skies have become so rare in the modern world that certain communities and land managers have begun applying for official Dark Sky status from the IDA. There are two certified International Dark Sky Parks in the U.S. (see sidebar) and two Dark Sky Communities. Each park and community has positioned itself as a place where astro-tourists can find a pristine night sky, unfettered by artificial light. The small community of Tekapo, New Zealand, is even angling to be the world’s first World Heritage Starlight Reserve, a designation from the United Nations Educational, Scientific, Cultural Organization (UNESCO). UNESCO has designated more than 800 World Heritage sites across the globe, but this would be the first focusing on the sky.

As light pollution grows, more tourists are traveling to the increasingly rare locations where truly dark skies can be found. But with simple public lighting ordinances, the night sky could return to our communities.

“I see the sky as a giant national park that’s in horrible shape right now,” says astronomer Dan Caton. “It doesn’t have to be this bad forever. The city of Tucson has had aggressive lighting ordinances for 40 years. You can see the Milky Way from downtown again. It could be that way for everybody.” •

HEART OF DARKNESS

Want to find a dark sky near you? It’s harder than you might imagine if you live on the East Coast, which suffers from the worst light pollution in the U.S. But surprisingly, the East is home to one of only two International Dark Sky Parks. Cherry Springs State Park in Pennsylvania is the world’s second gold tier International Dark Sky Park. This 48-acre state park is surrounded by the 262,000-acre Susquehanna State Forest, and far enough away from any bright community that its skies remain pristine. A field at 2,300-feet in elevation provides the perfect perch for amateur astronomers and its geographical location gives a great view of the nucleus of the Milky Way. You can even rent a mini-observatory for optimal viewing.

Also check out Spruce Knob, the highest point in West Virginia. The mountain isn’t an official Dark Sky Park, but according to IDSA’s Bob Parks, it’s one of the darkest spots on the East Coast.

“It’s almost as dark as some of the deserts in the West,” Parks says. “On a clear night, you can read by the light of the Milky Way at Spruce Knob.”

COAST WITH THE MOST

The Eastern U.S. suffers from the worst light pollution on the continent

Increasing development and sprawl are responsible for drowning out the night sky across much of the Eastern United States. In the past fifty years, light pollution has grown exponentially in the East, reducing visibility to just a few bright stars in places like Atlanta and D.C. Light pollution may seem trivial, but a growing body of scientific research suggests that overexposure to artificial lighting contributes to weaker immune systems and increased cancer risk.

Wildlife also suffer from light pollution. Sea turtles that have been nesting on dark beaches for 500 million years are aborting nests on brightly lit shores, and turtle hatchlings often crawl toward the lights of hotels instead of the ocean when they emerge from their nests.

HOW OUTDOOR LIGHTING TRANSLATES INTO LIGHT POLLUTION

HOW OUTDOOR LIGHTING TRANSLATES INTO LIGHT POLLUTION

The night sky in the U.S. is brightening by 5-10 percent annually. Outdoor lighting is largely responsible. Over 50 percent of light from a standard fixture is wasted, shining light into the sky instead of its intended target on the ground. The International Dark Sky Association advocates the installation of new lights and street lamps with hoods that direct wasted light toward the ground rather than skyward.