Two proposed Appalachian highways target the Southeast’s wildest landscapes, and new rail alternatives are headed down the tracks. Is Appalachia on board?

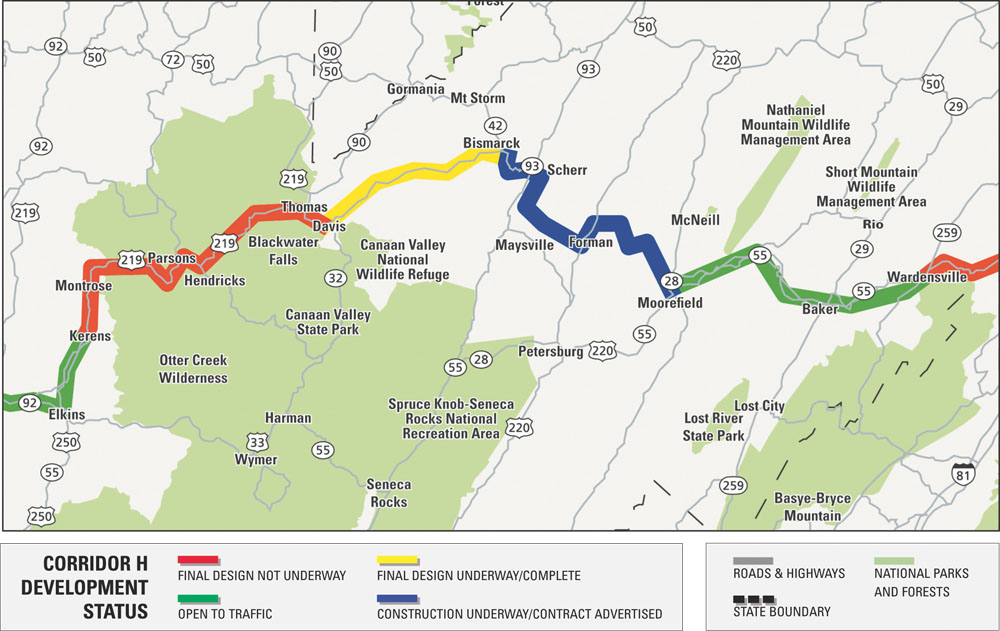

West Virginia Senator Robert Byrd—the longest serving member of Congress—wants to build a highway as his final legacy. Referred to as Corridor H, the four-lane highway would be an extension of I-66, connecting D.C. with tourist destinations in West Virginia.

Corridor H is part of the Appalachian Regional Development Act, a bill passed in 1965 to stimulate the economy of the Appalachian region through the creation of a 3,090-mile highway system. Fifty-five years later, that highway system is almost complete, with 2,672 miles of modern highway running through the mountains from Alabama to New York.

But many of the remaining highways to be built are slated to run through some of the most environmentally sensitive terrain in the Appalachians. Two of the most controversial roads yet to be built will travel through some of the South’s most beloved recreation areas. Meanwhile, the price for building these few miles of road has escalated, catapulting these remote highways onto the national stage. As federal and state governments wrestle with debt, should we bother finishing the last pieces of the Appalachian

Development Highway System?

Can Bin Laden Build a Highway?

President Obama removed funds for the last 42 miles of Corridor H from his 2010 budget, labeling the project a wasteful earmark. But then Senator Byrd re-inserted $4.5 million into the 2010 budget to help build a small section of the road between Bismark and Davis. Byrd calls Corridor H his “transportation crusade.” His earmark won’t go very far, however. Each mile of the road costs an estimated $20 million to build.

The national watch group, Citizens Against Government Waste, is holding Corridor H up as an example of political pork, labeling the highway a “Road to Nowhere.” Byrd’s budget play even prompted Fox News’ Sean Hannity to produce an “expose” on the road, depicting the highway as an example of government waste. Current traffic volumes on completed portions of Corridor H don’t warrant a four-lane super highway. The largest town on West Virginia’s portion of Corridor H is Elkins, which has less than 8,000 residents.

But tourism is West Virginia’s second-largest economic resource, and Corridor H is set to pass through Tucker County, home to two ski resorts, two state parks, and large swaths of the Monongahela National Forest. A West Virginia Department of Highways study estimates a completed Corridor H could boost tourism related income by as much as 10 percent.

“This road will reduce travel time from D.C. by about an hour and a half,” says Bill Smith, director of tourism for the Tucker County Convention and Visitors Bureau. The trip currently takes around four hours. “It will turn Canaan Valley into a day trip for D.C. residents.”

The Appalachian Regional Commission’s own studies are less optimistic. A 1998 report by the commission showed that seven of the 12 corridors actually yielded a negative economic impact. For example, I-68, running from Morgantown, W.Va., to Cumberland, M.D. lost a quarter for every dollar spent. The most successful Appalachian Highway corridors service cities with at least 25,000 people. The least successful corridors are in rural, isolated areas, like Corridor H.

Now, Senator Byrd is looking beyond the economic justification for the road, instead focusing on national security. Lately Byrd has been pitching Corridor H as an escape route for D.C. residents in case of a terrorist attack. If Byrd is able to get H designated as a National Defense Highway, the road would be given the same funding status as an interstate.

Bonnie McKeown, a spokesperson for the Potomac Stewards, calls the terrorism justification preposterous, predominantly because the state of Virginia has refused to build their 20-mile section of the highway from I-81 to the West Virginia border.

“The sections of H that are already built were justified,” McKeown says. “They connected towns that needed better routes. But this last section serves no purpose.”

Hugh Rogers, executive director of the West Virginia Highlands Commission, spearheaded a legal battle over Corridor H for nearly a decade that resulted in the reroute of the corridor around environmentally and historically sensitive areas like Blackwater Canyon near Davis. He sees no reason to make a four-lane connection between the existing stretches of Corridor H.

“We could accomplish the connections by improving the existing two-lane roads with wider shoulders and truck passing lanes,” Rogers says.

Two Lanes or Four?

A good road between point A and B could be argued as an American Right, but does that good road have to be four lanes? The last unbuilt section of Corridor K, a road meant to connect Asheville with Chattanooga. has to pass through the Ocoee Gorge and Cherokee National Forest in southeast Tennessee. The finished portions of Corridor K on either side of the gorge are four-lane, but environmental organizations are questioning whether the gorge portion should be four-lane as well.

“What’s wrong with a two-lane road? Why not improve the current route through the gorge and call Corridor K finished?” says Lucy Bartlett, past chairman of WaysSouth, a grassroots organization monitoring transportation issues.

The current route through the Ocoee Gorge is U.S. 64, a windy, tight road flanked by the river on one side and rock cliffs on the other. The road was originally built during the Civil War and features rock overhangs easily hit by trucks, and hairpin turns that two opposing trucks can’t pass through at the same time. Signs along the the road warn drivers: “10 mph: be prepared for trucks in your lane.”

“The road right now isn’t safe,” says Larry Mashburn, owner of the Ocoee Adventure Center on U.S. 64. “I send buses full of people on that road every day. It’s a concern.”

Mashburn, like many locals, is conflicted when it comes to the Corridor K project. He wants a safer route through the gorge, but is wary of building another road through the Cherokee National Forest. Wilderness boundaries meet the road in sections, and digging further into the rock cliff will leech acid into the Ocoee and threaten sensitive species on either side of the road. Futhermore, the cliffs are unstable, as proven by a massive rock slide that recently shut down the entire road through the gorge.

“At public meetings, all we hear from locals is, ‘Why has it taken you so long to build us a road?’” says Jennifer Flynn, information officer for the Tennessee Department of Transportation (DOT).

The county councils that would be served by the Ocoee portion of Corridor K have voted the road their number one priority, and an economic study last decade suggested that Corridor K could result in 7,000 new jobs.

The original four-lane Corridor K route proposed in 2004 met with public outcry over the environmental implications of the project. Having learned from their previous mistakes, the DOT has created a Citizens Advisory Board and has narrowed potential routes down to four options, each 2,000 feet wide, providing “wiggle room” to avoid valuable resources. Flynn says that a two-lane option is more appealing from an engineering perspective because it’s easier to squeeze through the sensitive ecosystems.

Hole in the Mountain

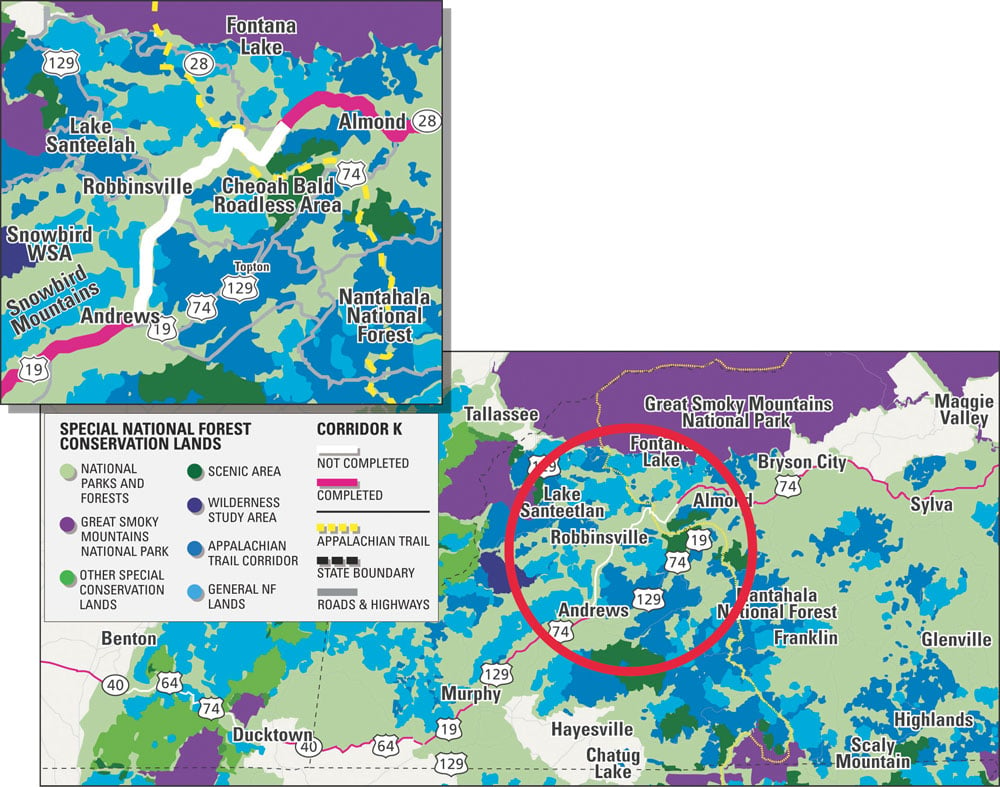

The North Carolina section of Corridor K is even more controversial. The current design for the ten-mile stretch would entail digging a 2,870-foot tunnel directly below the Appalachian Trail. The total cost for this section is a staggering $383 million—almost $200 million would go to building the tunnel.

Constructing a tunnel could be avoided entirely if the highway footprint is reduced from a four-lane to a two-lane. But NC DOT has refused to consider that option so far.

According to the Southern Environmental Law Center (SELC), the NC DOT’s failure to even consider a two-lane option is a significant legal oversight that could be contended in court when a final environmental statement is released late in 2010.

The Army Corps of Engineers has similar concerns. The Corps recently told NC DOT that the current preferred four-lane alternative to Corridor K would create adverse stream and wetland impacts and suggested that the “alternative of upgrading and improving existing two-lane roadways should be given full consideration as a practical alternative.”

According to the DOT’s own studies, existing routes in the area are sufficient to handle traffic projections for the next 20 years, and spot improvements to those roads would make them sufficient for decades beyond that. Even more troubling is that the DOT estimates that the new super four-lane highway would not decrease travel time in the area.

Stacy Oberhausen, NC DOT’S project coordinator for Corridor K, says the Corps’ letter hasn’t altered the state’s plans for a four-lane road. “If the Corps expects a two-lane alternative or upgrades, we’ll evaluate those options, but that doesn’t mean a two-lane will be the option we construct.”

Do the Locomotion

Do the Locomotion

A comprehensive highway system has been important to Appalachia’s economy, but it’s not nearly as critical to the region’s future as railways, says the Appalachian Regional Commission. Their recent report, Network Appalachia, spells out the significance of rail lines for connecting Appalachia to the global economy. Shipping goods from U.S. distribution centers to coastal ports via rail is 71 percent cheaper than using trucks.

“If we don’t link the Appalachians to the global economy via rail corridors, the region will once again be left behind,” says Scott Hercik, transportation coordinator for the Appalachian Regional Commission.

The Appalachian Regional Commission recently received $76 million in federal money for non-highway projects like rail corridors, and a few progressive rail projects are already in the works in the Appalachians. Even something as distant as the widening of the Panama Canal may have an impact on Appalachia’s transportation future. Once the Panama Canal is widened, Asian manufacturers can ship their goods directly to the East Coast. From there, the cheapest way to distribute them inland is by rail or ship. A 70 percent increase in rail freight traffic is expected by 2020, which will likely result in far fewer trucks on Appalachian highways.

“We’re not interested in building highways. We’re interested in economic success,” says Hercik. “We need to be ahead of the curve with the move toward rail transportation.” •

TRANSPORTATION BREAKDOWN

Corridor H in West Virginia

> Location: Kerens to Moorefield, near ski resorts and Monongahela National Forest

> Length: up to 76 miles

> Cost: $1.5 billion

> Purpose for building the road: Connect I-81 in Virginia with I-79 in West Virginia, delivering tourists to Tucker Coutny and Randolph County in the process.

> Environmental Concerns: The projected route cuts through the Monongahela National Forest and must somehow traverse the Blackwater Canyon near Davis. The federally endangered West Virginia Northern Flying Squirrel is also found along the route.

Corridor K in Tennessee

> Location: Near the Ocoee Gorge through Cherokee National Forest.

> Length: 21 miles

> Cost: Undetermined

> Purpose: Provide local residents and trucks an alternative to the current U.S. 64, improving access between Ducktown and Cleveland, Tennessee.

> Environmental Concerns: Only preliminary corridors have been defined, however, Wilderness areas exist near both the northern and southern corridor options. An extensive mountain biking and hiking trail system exists on the southern side of the gorge, which could be affected by potential routes, and additions to the Little Frog Mountain Wilderness Area are being considered that could impact northern corridor options. Further fragmenting the Cherokee National Forest and degradation to the Ocoee watershed are of a high concern.

Corridor K in North Carolina

> Length: 10 miles

> Location: Stecoah to Andrews through Robbinsville.

> Cost: $383 million, roughly $38 million per mile

> Purpose: Re-route U.S. 74, providing an alternative route around the Nantahala Gorge, and improve connectivity and economy within Graham County.

> Environmental concerns: The road could permanently damage the viewshed from the Appalachian Trail. Over three million cubic yards of rock would have to be excavated from the route. A 2,847-foot tunnel through Stecoah Gap below the A.T. would be required if the road is four lanes. A separate tunnel, nearly a mile long, is required through the Snowbird Mountains. The rock to be excavated has the potential for leaching acids into the surrounding river systems.