Mountain biking and more at a remote escape on the Tennessee-Kentucky state line

“Bear!” I shouted, skidding my bike to a halt. “And baby!”

I was riding around a corner on the Collier Ridge trail when the hulking mama reared up to guard her small cub. I backed up as our group gathered, and we watched the bears run off into the woods.

Cautiously, we continued riding through the backcountry near Bandy Creek on the Tennessee side of the park. This fun loop is about six rolling miles with 500 feet of climbing and the same amount of downhill coming in regular fast bursts. It was a Friday morning in early June. We’d gotten a late start after staying up too late the night before, celebrating our long-delayed reunion and return to Big South Fork National River and Recreation Area, which straddles the Kentucky state line.

At the trail junction, my buddy Boberts and I parted ways with our wives. They seemed quite pleased with the split, given their target was afternoon cocktails at the campers. Our goal was to ride through the heat and humidity and complete the entire 34-mile epic. After up-and-down doubletrack on Duncan Hollow Bypass, we turned onto the Duncan Hollow singletrack. I certainly appreciated the cooling breeze on the plunging downhill half. But climbing back up, my head was pounding, and my hair felt like it was on fire. Having been trapped in the Low Country all year due to family and work obligations, I wasn’t ready for steeps in the heat. While Boberts pushed onward, I reluctantly headed back to camp to cool down.

A Taste of West in the Southeast

Each time we’ve come to the Big South Fork National River and Recreation Area, something has gone wrong, usually in a comical way. Maybe it’s because this lesser-known National Park Service unit is out there. And I mean out there, in one of the most remote and rugged regions in the Southeast. Located on the Cumberland Plateau, this roughly 200-square-mile park averages around 750,000 visitors per year. Most folks come for biking, hiking, and paddling. The rec area is way less crowded than big-name units like Great Smoky Mountains National Park or the Blue Ridge Parkway, which are seeing record annual numbers around 14 and 16 million, respectively. To me, Big South Fork’s remoteness makes it the most Western-like of the Southeastern parks.

My first trip was for whitewater kayaking during early spring about 15 years ago. Our group of 20- and 30-something paddlers was exploring the creeks and rivers of the Southeast. We spent a few days running the classic seven-mile class III+ section from the Confluence to Leatherwood Ford. Flows were good, somewhere between 2000-3000 CFS. The rapids were fun. And the wooded canyon scenery, with Big South Fork of the Cumberland River rushing through massive sandstone boulders, was the best part.

That said, back then, the town of Oneida didn’t have a lot of post-shuttle dinner options. Each night, we had a few choices: sandwiches in a gas station, pizza in a gas station, or fried other stuff in a gas station. Let’s just say, we never ran out of gas on that trip. Luckily, there are more options these days. That said, don’t show up expecting results for fancy search terms like “gastropub.” That’s not why you come out here.

After bailing midday, I went back to our camper at the pleasant Bandy Creek Campground. I spent a few hours focusing on cold water, both drinking it and dumping it on my head. By late afternoon, I had reduced my core temperature enough to save face with further biking. Just before setting off, a dazed Boberts rolled into camp having gutted out the epic route. When I invited him to join for more, his eyes widened, and he practically ran inside his air-conditioned camper.

Riding solo, I made a figure eight, up Collier Ridge West and down West Bandy, with the latter trail being a bit rougher and more technical but still fast and fun. Then I climbed the road and descended Collier Ridge East. At one point, I slammed on the brakes. A huge black bear was climbing a large tree. Startled, it jumped down with all four paws extended in mid-air. It landed in a crouch and stared at me before barreling downhill.

Kentucky Hikes and Historic Sites

On Saturday, we decided to rest our legs by exploring the Kentucky side of Big South Fork. The drive emphasized the area’s remoteness when a navigation app suspiciously led us over Yamacraw Bridge to the front yard of some random dude’s house. He was riding his lawnmower, puzzled by the four equally confused hikers looking for a trailhead. So, I used the NPS map brochure to get us to the Yahoo Falls parking lot, where we met a family who had also stopped by that same guy’s house before correcting course.

First, we walked the two-mile trail out to Yahoo Arch, one of several hundred natural sandstone arches found within the rec area. This impressive feature includes not just the sweeping arch but a rock window and a series of bigger and smaller caves. Full disclosure: I am kind of a fanboy for geomorphology—essentially how landforms take their shapes. Scrambling up above the arch, I could sort of see it. During high runoff, water had once tumbled over ledges and pooled above a cave, swirling and eroding the backside bedrock to eventually create Yahoo Arch.

On the return hike, we walked through the alcove behind Yahoo Falls, which was only a trickle after a dry spring. Dropping a stout 113 feet, it’s the state’s tallest waterfall, and one of seventeen in Eastern Kentucky included on the Kentucky Wildlands Waterfall Trail. On the hike out, we met a young group of Sheltowee Trace section hikers. Lacking a map, they had errantly turned uphill away from the 343-mile trail that starts near Big South Fork and ends at the northern boundary of Daniel Boone National Forest. I gave them our NPS map brochure, and they trooped back down to the river to trudge onward.

Our next stop was the Blue Heron Mining Community. This abandoned coal town, which operated from 1937 to 1962, is now a fascinating outdoor NPS museum. Our walking tour took us past the preserved tipple, where extracted coal was prepared for transport to market. Above, we crossed the bridge that carried the mining carts over the river. We only had time for a fraction of the 10 miles of paved paths and dirt trails passing through the area, which lead to steel-frame ghost structures, the gated mine entrance, and viewpoints in the hills above the river.

Baffled as to why such an excellent site was so empty on a Saturday during peak season, I dropped inside the small visitor center to inquire. The on-duty ranger looked up in surprise.

“You’re number 27 today,” he said sheepishly.

The ranger explained the ghost town once saw 300 visitors per day, with most arriving on the Big South Fork Scenic Railway. Then the track washed out. But recent repairs mean the trains may return in the future.

Back for Singletrack

On Sunday our wives went hiking in search of more stone arches. Meanwhile, Boberts and I rode away from camp determined to right a wrong. Five years ago, we’d come here in late fall on a last-minute bikepacking trip after our original route was smoked out by forest fires. We had little time to plan, and it didn’t go as hoped. We ended up on some rough horse trails and had to carry loaded bikes up cliffs and down stairs and ladders. We camped twice in manure-filled horse camps, got lost, ran out of water, and were saved by some generous homesteaders with a well. After I wrote about the misadventure for a bikepacking blog, a local rider messaged me about how bummed he was we completely missed the best singletrack in the park. I promised we would be back, and finally we’d made it.

Fortunately, after years of buildup, Grand Gap Loop did not disappoint. We started early to beat the heat, and enjoyed about 6.5 miles of fast turns, ledge drops, and cliffside trail offering stunning views above the canyon. At Angel Falls Overlook, we met some friendly regional riders from the clubs that maintain the trails. We rode with them partway on the worthy John Muir Trail, which winds away from the rim for about 7.5 miles into dense forest that conceals alcoves and caves. It was a triumphant visit to what’s become a favorite place. Our only remaining goal was to figure out when we’d next return to the Big South Fork.

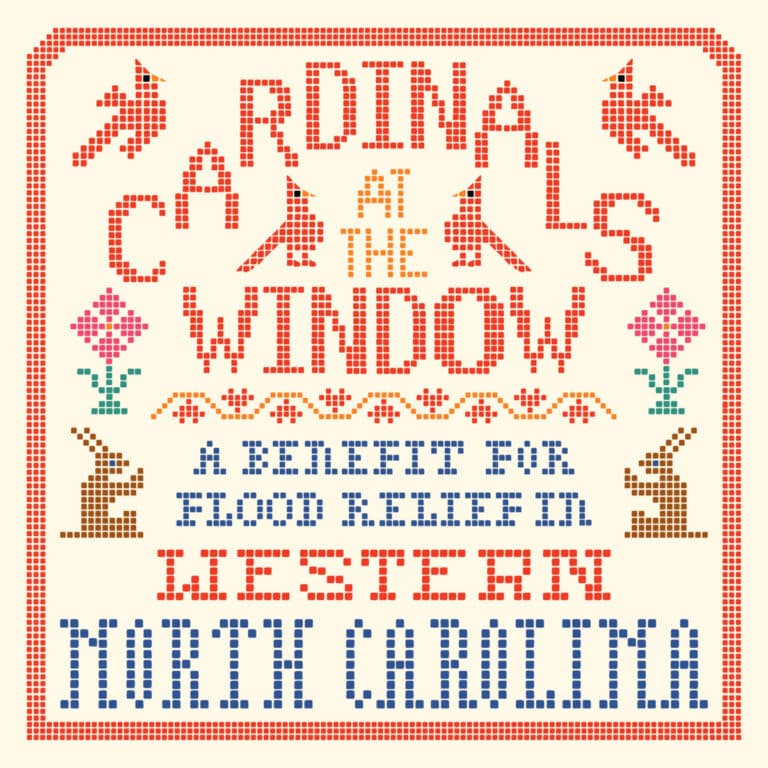

Cover photo: By Mike Bezemek