From tool to toy, the bike has served many roles over the course of history. Follow along on this two-wheeled tribute to learn how the bike came to be and what it’s doing for our communities and economies 200 years later.

History of the Bike

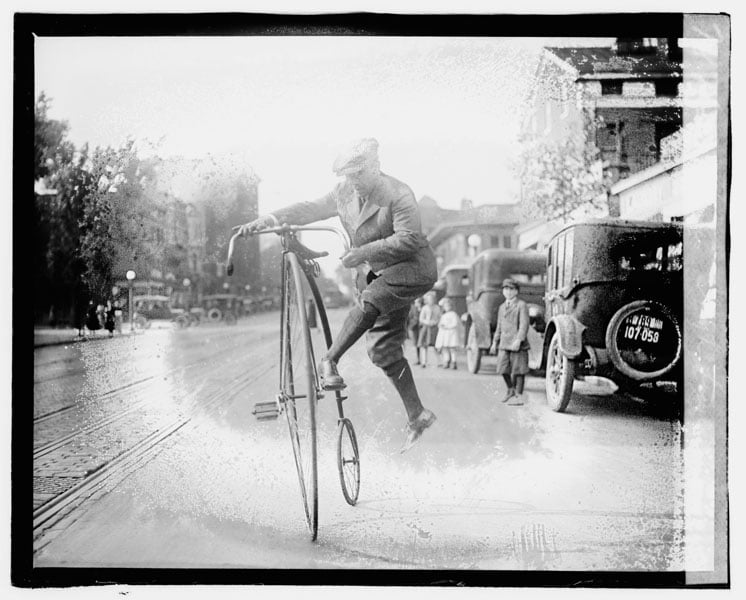

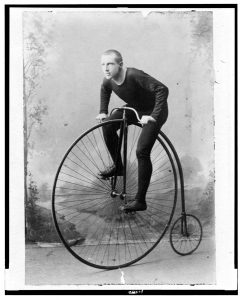

The first two-wheeled contraption was invented by German Karl Freiherr von Drais in 1817. After the historic 1815 eruption of Mount Tambora, crops failed throughout Germany, making it nearly impossible to keep the country’s main transportation, horses, alive. The “hobby horse” was Drais’ solution. This early version of the bike looked not unlike something out of the Flintstones—made entirely of wood, the unwieldy “swift walker” had no pedals and was powered much like a present-day Strider kid’s bike.

Near the turn of the century, bicycles began to resemble those of today—two same-sized wheels with pedals attached to a rear crank. That bike, known as the “safety bike” (or Rover Safety), initially had tires made from hard rubber, but by 1894, pneumatic tires, that is tires with inflatable tubes, were being used. The modern bicycle was born.

That same year saw the bicycle becoming not only a utility tool but also a means of exploration. Annie Kopchovsky (aka Annie Londonderry) was a Jewish mother from Boston who became the first woman to travel around the world by bike. Her journey was inspiring, unconventional, and probably exaggerated. Nonetheless, Londonderry’s achievement became a symbol for women’s rights. Her subsequent fame helped bring about changes in women’s antiquated and restrictive fashion.

By the end of the 19th century, bicycles were a common sight in American cities. After an 1894 railway strike in California, young men were employed to deliver telegraphs and mail by bike, thereby introducing the first two-wheeled employment, that of a bicycle courier. To this day, bike messengers are still used in urban areas for delivering mail, food, and everything in between.

When Maurice Garin won the first ever Tour de France in 1903, his steel frame La Francaise weighed in around 39 pounds. It had wooden wheel rims and wonky drop bars.

Garin’s bike was a fixed-gear single speed, which meant there was no coasting on the downhills. Freewheels (which allowed coasting without pedaling) and multi-speed rear derailleurs didn’t come along for another couple of years, and early versions of the multiple-geared derailleurs required riders to dismount and manually shift the chain.

During the 1920s and ‘30s, some of the bike industry’s biggest names like Shimano, Campagnolo, and Schwinn entered the scene, bringing with them a host of innovations like the first quick-release hub and cable shift derailleurs. Bicycles, it seemed, were here to stay.

But as World War II came to a close, so too did America’s infatuation with bikes. Cars soon replaced bicycles as the symbol of freedom and fortitude. For decades, bikes were delegated as children’s toys, shelved as soon as the kids could drive.

[nextpage title=”Read on!”]

The Biking Boom

Between 1960 and 1970, the bicycle eked its way back into the market, thanks to wanderlust-deprived adults yearning for a more intimate way to see the world. In 1960, 3.7 million bicycles were sold in the United States. Just 10 years later, that number had nearly doubled to 6.9 million.

In 1962, the first bikeway was created in Florida. Paul Dudley White, President Eisenhower’s doctor, dedicated the new bike friendly path, boldly stating, “The American public is a slave to the automobile.” Cycling, he believed, could change that.

Indeed, cyclists were changing that by pushing the limits on how far and how fast they could ride a bike. Velodromes, or indoor tracks, like the Dick Lane Velodrome in Atlanta (built in 1974), had long been at the core of the cycling scene, but road riders were hungry for more.

Stage races and long-distance road tours became their answer. In 1975, the Assault on Mount Mitchell was born. In its early years, the Assault saw so much interest that National Park Service and Mount Mitchell State Park officials forced ride organizers to cap the number of cyclists at 800.

Elite cyclists began noticing the Southeast’s rolling terrain and mild climate. Time trial and criterium events in places like Rock Hill, S.C., date back to the late ‘70s. The Spring Races, which started in 1981, established the Upstate as a cycling destination.

Almost 20 years before Tour de France domestique George Hincapie moved home and forever sealed Greenville, South Carolina’s place among the world’s top cycling destinations, professional cyclists like Greg Lemond and Lance Armstrong had already experienced the city’s potential thanks to the Tour DuPont. Formerly the Tour De Trump, the Tour DuPont was a high-stakes cycling stage race that was created as the North American rival to the Tour de France. President Donald Trump himself was an early sponsor of the East Coast race for its first two years (1989 and 1990), but later, the DuPont chemical company assumed sponsorship until 1996.

By then, bicycles were a mainstay of American culture. Once the mountain bike made its debut, the possibilities for two-wheeled travel were limitless.

Dawn Of The Mountain Bike

For Mike Palmeri, original owner of Cartecay Bike Shop in Ellijay, Ga., bikes were everything. During his time as part of the Schwinn BMX Team, Palmeri and his teammates rode track bikes on the velodrome to train for upcoming events. When the first mass-produced mountain bike, the Specialized Stumpjumper, entered the market in 1981, the team started training on mountain bikes instead. That changed everything.

In 1983, Palmeri showed up at what many consider the region’s first mountain bike race: the course was a 13.5-mile trail called River Loop, which still exists today.

“It was like a big party. It wasn’t really about the mountain bike racing,” says Palmeri of that ’83 race. “Nobody cared who won. You rode with hiking boots, that was the shoe of choice, blue jeans, and maybe an old road jersey or something. There were no primadonnas. It was just a big hippie party.”

“Everyone at first thought it was just a fad, but the popularity grew pretty quickly,” says Barry Jeffries, owner of Dirty Harry’s Bikes in Verona, Penn.

Seemingly overnight, the mountain biking culture mushroomed. Former dirt bike riders brought the spirit of adventure. BMXers came with next-level bike handling, and roadies burnt out on chasing pavement showed up in spandex kits, freakishly strong and psyched. These biking outliers had finally found their calling.

[nextpage title=”Read on!”]

Taking to the Trails

Laird Knight moved to Davis, W.Va., in the fall of 1982 and opened up Blackwater Bikes the next spring. That first year, Knight struggled to even order mountain bikes for the shop, let alone find people to buy them.

In order to survive, Knight knew he was going to have to concoct a reason for mountain bikers to come to him. He created the Canaan Mountain 40K. “That race had 12 people in it, and it turned out to be a lot more than 40K. Either bikes broke down or people broke down. Nobody finished, including me.”

That unfinished sufferfest put Davis and Canaan Valley on the map. Attendance soared for Knight’s increasingly grueling races, as did the Valley’s reputation as a mountain bike destination. In 1988, Knight hosted the first Mid-Atlantic National Off Road Bicycle Association (NORBA) Nationals with tremendous success. Over 400 people showed, doubling Davis’ population in a mere weekend.

Two hours south, Gil Willis and his wife Mary opened up the Elk River Touring Center in Slatyfork, W.Va., at the base of Snowshoe. The summer of 1985, they bought a fleet of mountain bikes for visitors to rent, one of the first businesses to do so east of the Mississippi. Surrounded by thousands of acres of national forest, and in close proximity to the Greenbrier River Trail, it wasn’t long before Elk River Touring Center became another Mid-Atlantic biking hub.

Their signature event, the West Virginia Fat Tire Festival, was a mainstay of the West Virginia mountain biking culture for over a decade. Before Tour de France winner Floyd Landis hit the big time, even he was seen racing the trails around Elk River in jean shorts.

In 1992, Knight rocked the mountain biking community with the introduction of a relay-style, through-the-night, 24-hour race. It started at noon on Saturday and went until noon Sunday, which made Canaan Valley’s already brutal terrain that much tougher. By 1995, more than 1,000 racers were competing at 24 Hours of Canaan.

BRO-TV: Then & Now—Mountain Biking in Canaan Valley from Blue Ridge Outdoors on Vimeo.

The Pivotal Age of Access

From 1981 to 1995, the mountain bike saw incredible upgrades and improvements. Riders could now have bikes with full suspension, disc brakes, and integrated brake and gear levers. The sport was looking less counterculture and more mainstream. It helped that in 1996, mountain biking was introduced to the Olympic Games, which were set for Atlanta, Ga., that year.

“The Olympics took and legitimized mountain biking to the world,” says Shenandoah Mountain Touring and Stokesville Lodge owner Chris Scott.

Trail builder, race promoter, access advocate—Scott is the rightful “Godfather of Mountain Biking” in Virginia. In 1999 he started the Shenandoah Mountain 100, tapping into the same camaraderie of endurance races that was key to Knight’s 24-hour success.

Trail access soon became an issue. Around 1987, the Kennesaw Mountain National Battlefield Park forbade mountain biking, and that led to a domino effect all throughout northern Georgia and the Southeast.

“Before that time, any trail had been open to mountain bikers,” says Southern Off-Road Bicycle Association (SORBA) Executive Director Tom Sauret. “Land managers didn’t know what a mountain bike was.”

Enter the International Mountain Bike Association (IMBA), the nationwide representative voice of mountain bikers. The launch of IMBA’s Trail Care Crew in 1997 marked the beginnings of mountain bikers’ reputation as dedicated trail stewards.

By the late 1990s, the change in land managers’ attitudes toward mountain bikers was palpable. After years of advocacy and relationship building, Roanoke’s riders finally opened up Carvins Cove in 1999. Hikers, equestrians, and bikers helped defeat the threat of development in DuPont State Forest, opening up a flood gate of enthusiasm for cycling in the mountains of western North Carolina. The early 2000s were graced with miles upon miles of singletrack and greenways being incorporated into urban centers like Roanoke, Greenville, Knoxville, and Charlottesville.

[nextpage title=”Read on!”]

Two-Wheeled Change

Recent studies show that cycling alone contributes $133 billion annually to the economy. Additionally, the Outdoor Industry Association’s latest report found that Americans spend $97 billion on cycling and skateboarding gear every year. With numbers like that, cyclists’ impact on economies locally and nationally is impossible to ignore.

“Cyclists now are seen as constructive problem solvers who just don’t complain about things but actively change them, ” says Kyle Lawrence, President of the Shenandoah Valley Bicycle Coalition. For 35 years, the coalition has been actively promoting bicycle friendly initiatives in the greater Harrisonburg area, including the construction of greenways and availability of bikes for youth in the public school system, as well as trail maintenance in nearby national forests.

Sue George, a retired national and collegiate level cyclist, founded Charlottesville Area Mountain Bike Club (CAMBC) in 2003. She says it was important for such a fast-growing sport to be taken seriously, especially by local and national political leaders. CAMBC members swarmed the nation’s capital in 2005 for the first-ever IMBA 24 Hours of D.C., a 24-hour lobbying campaign that demonstrated, if nothing else, the sheer scope of the mountain biking population.

“Before CAMBC, we had a lot of smaller groups riding together in a fun way but not necessarily in a way that promoted the advocacy of the sport,” says George. “Now we have this greater sense of responsibility in giving back to the community and that’s come with the maturity of the sport.”

George is hopeful that the explosion of National Interscholastic Cycling Association (NICA) leagues will continue to nurture responsible, sustainable growth well into the future of cycling. Founded in 2009 in California, NICA leagues are now available for high school students in 19 states, including Tennessee, Georgia, Alabama, Pennsylvania, North Carolina, and Virginia.

Today, overuse, trail ethics, and access issues dominate the conversations on bike forums and club meetings alike. Developments like the e-bike are of particular controversy, threatening to pit cyclists against cyclists: some consider these bikes as a formidable step forward in urban commuting and exercise for the elderly, others are worried these motorized bikes will dismantle decades of trail advocacy.

Another peril on the horizon? Money. Recreational Trails Program and Clean Water Trust funds have traditionally been the financial means for many regional trail projects. Under the current administration those funds may very well dry up in the months to come, which means clubs like the SVBC and SORBA will need to get creative. Fortunately, there are more stakeholders in the sport than ever before.

“We have shifted the argument from health and environmental protection to where now, we see recreation as the new conservation,” says SORBA Executive Director Tom Sauret. “Economic impact numbers do perk up the ears of some of our political leaders.”

According to the League of American Bicyclists, North Carolina’s Outer Banks invested a one-time sum of $6.7 million in bicycle infrastructure. The result has been an annual nine-to-one return, with a conservative estimate of $60 million generated each year through bicycle related tourism. An average of 680,000 cyclists visit each year, which supports over 1,400 relevant jobs in the area.

When Greenville, S.C., cut the ribbon on the Greenville Health System Swamp Rabbit Trail in 2011, the greenway was an instant success. The Greenville Health System’s Three Year Findings survey on the Swamp Rabbit Trail indicated that businesses were seeing upwards of 85 percent in sales and revenue increases. The trail, which connected downtown Greenville with nearby Travelers Rest, was a boon for development. Now businesses looking to relocate near the trail have a hard time affording trailside property, let alone finding a site that’s still available.

The Swamp Rabbit Trail was one of several recent examples of private-public partnerships. Many ski resorts are opening their slopes to mountain biking in the summer months. And in Louisville, Ky., area residents there are anticipating the opening of the Parklands, a 4,000-acre piece of property that will have 50 miles of linear trail experiences. The $130 million in funding for the park came not through any grants but private donations.

As big bike brands like Trek continue to buy up formerly independent bicycle retailers, bike shops are going to have to do more than service bikes. They will continue to be hubs of advocacy, fundraising, youth cycling development, lobbying for bicycle friendly initiatives, and gateways for progress. The golden years of bicycles aren’t over—they’re just getting started.

“The bike is king now,” adds Chris Scott. “We just need people to step up.”