“People were lying on the edge of the trail, completely in shock, wrapped in emergency blankets and waiting for the helicopters to come and take them out,” recalls mountain biker Rich Dillen. “Some of those bikers ate it so bad, they weren’t thinking straight anymore. I thought, ‘that could be me.’”

Dillen is talking about the TransRockies Challenge in Canada. Billed as the hardest mountain bike race in North America, the TransRockies punishes bikers for seven days as they pedal through 600 kilometers of the toughest terrain British Columbia has to offer. In 2006, a series of waterbars delivered a number of DNFs (Did Not Finish) during the first stage of the race. And that was just the first day. There were six more days of waterbars, rock gardens, high elevations, thousand-foot climbs followed by thousand foot climbs. The number of obstacles standing in a competitor’s way of the TransRockies finish line are staggering, making failure a much more likely outcome than success.

That’s exactly what athletes like Dillen look for in a race. It’s not that they want to get hurt. It’s simply that they want to stack the odds so heavily against themselves that failure is all but certain. Experienced athletes in a variety of outdoor sports are searching for soul-crushing challenges that all but guarantee failure. But that’s okay, because failure isn’t a bad thing to these athletes. Failure isn’t failure. Failure is success.

——————–

THINGS FALL APART

“Everyone I know has tried to do something really stupid at some point in their lives,” says Rich Dillen. Dillen’s most recent exercises in stupidity include trying to ride 100 consecutive miles through the mountains of Georgia in the sweltering August heat—without water; trying to summit Mount Mitchell, the tallest peak east of the Rockies, on a singlespeed rigid mountain bike; and trying to traverse 600 kilometers of the Canadian Rockies on that same rigid singlespeed.

“It’s the next logical step in any sport,” Dillen says. “You look at some challenge and you say, ‘I wonder if I could do this?’ And you do it.”

Or you don’t. The extreme endurance bike races that Dillen enters—Pacific Traverse, Double Dare, Pisgah Mountain Bike Adventure, TransRockies Challenge—have a success rate that hovers around 50%. Yet they’re highly sought after races not in spite of their difficulty, but because of it.

For runners, the all-but-guaranteed DNF is the Barkley 100. The race, held in eastern Tennessee every spring, has 52,900 feet of climbing, more than any other 100-mile race in the world. Compare that to the Hardrock 100, one of the most revered ultra races, which has a mere 33,000 feet of climbing. Within the first mile of the Barkley, you climb 1,500 feet. The course is so tough, you have to submit a letter of intent explaining why you are worthy of even setting foot on Barkley’s hallowed ground. During the race’s 20+ years, only six runners have ever finished. Still, runners clamor to be one of the chosen few standing at the starting line, even though most of them don’t expect to ever reach the finish line.

“Why do I attempt the Barkley even though I know I have no chance of finishing it?” asks Matt Mahoney, a long-time ultra running icon who’s attempted—and failed—to complete the Barkley several times. “If I was guaranteed to succeed, I wouldn’t be challenging myself.”

Mountain biking’s answer to the Barkley 100-Miler could be The Most Horrible Thing Ever, a new event created by Eric Wever and Pisgah Productions, the race event company that’s famous for creating the Pisgah Mountain Bike Adventure Race (PMBAR) and the Double Dare Mountain Bike Adventure. PMBAR is a single day, 70+ mile checkpoint race through some of Western North Carolina’s toughest singletrack. The Double Dare takes the same concept and adds a second day of riding. Wever aims for a 50% completion rate when creating his race courses, but his newest challenge, The Most Horrible Thing Ever, was created with the thought that nobody would finish.

“It’s the hardest thing I’ve ever put out there,” Wever says. The race starts at midnight on a Friday and doesn’t finish until noon on Sunday. Thirty-six hours and six stages of racing begin with a 50-mile stage right from the starting line. It gets worse from there. And yet, bikers jumped through hoops just to be allowed to compete in the challenge, sending Wever complete biking resumes in hopes of being deemed “worthy” of the challenge.

During the inaugural run of The Most Horrible Thing Ever, only two bikers were able to complete the race. The “winner” (there are no prizes or race entry fees) biked 200 miles through Pisgah in 36 straight hours. Most of the rest of the entrants quit after the first or second stage.

“None of these racers want to fail, but it’s a very real part of the challenge,” Wever says. “There are so many unknowns. Mechanicals, navigation errors, fatigue, dehydration—there are so many ways for people to get a DNF. Racers are acutely aware of that fact when they line up at the starting line, but that’s all part of the appeal. The uncertainty, the opportunity to fail, is what makes my race an adventure.”

——————–

WHEN LEARNING HURTS

Failure is a harsh word—perhaps too harsh to be applied to an athlete who pedals through only five of the six stages of The Most Horrible Thing Ever. Is it a failure to only run three laps of Barkley?

“Winning isn’t everything,” ultrarunner Mahoney says. “I consider it a success if I can run one or two loops of the Barkley’s five loop course.”

Still, most athletes start a race intending to finish it.

“Failure is failure,” concludes Kristen Dieffenbach, a nationally-ranked professional adventure racer and sports psychology consultant. Through her consulting service, Dieffenbach helps athletes enhance the mental side of their performance. During her “other job,” she competes in the toughest adventure races in North America.

“So much can go wrong during an expedition-length adventure race,” she says. “That’s part of the draw.”

In 2006, Dieffenbach competed in Primal Quest as captain of the Pennsylvania based GOALS team. Primal Quest is considered the superbowl of adventure racing and perhaps the toughest expedition-length race on the planet. For seven straight days, Primal Quest pits its competitors against the elements in some of the most severe environments in North America. According to one study, 85% of Primal Quest competitors suffer from auditory and visual hallucinations during the race because of sleep deprivation and malnutrition. In 2004, a competitor died on the course, prompting many to ask if the race wasn’t too difficult.

During the 2006 Primal Quest, Kristen Dieffenbach and her team had to trudge through the deserts and canyons of Utah for seven days in triple digit heat. There were 50,000 feet of ropes courses alone, to say nothing about the whitewater swimming, mountain biking, and desert trekking. But it wasn’t the course that got to Dieffenbach and her team. It was her mountain bike.

“I had huge mechanical issues with my bike—an astronomical amount of flats,” Dieffenbach says. “Even the mechanics were baffled. Ultimately, it kept us from finishing. But that’s adventure racing. It’s about the great unknown. There are a lot of elements you can’t control. The Primal Quest experience was miserable, but you have to look at it and say, ‘let’s go back and do it again.’”

That urge to seek out failure—or at best, uncertainty—is a foreign concept to most Americans, who live in a society that is overwhelmingly obsessed with success. If anything, failure has become our cultural nightmare. In the outdoor sports world, fear of failure could be one of the reasons why mainstream races continue to shrink in length and difficulty. The most popular adventure races now are shorter sprint races, and team races have become the most popular mountain biking format.

“The higher success rate of a team race is appealing to a lot of people,” Wever says. “It’s a really safe environment that allows for success. A lot of 24-hour team racers have four back-up bikes and full support crews. If their bike breaks, they can run to the finish line and get another one.”

The popular 24-hour race format allows people to dabble in endurance racing while enjoying a low-risk environment that almost guarantees a certain level of success. In most 24-hour competitions, teams don’t even need to race the full 24 hours to complete the race. A minimum amount of laps is all it takes to be considered an official finisher, resulting in a completion rate close to 100%. Just like the elementary school 5K where everyone gets a trophy, everyone walks away from a 24-hour race feeling like a winner, and nobody has to stray too far from their comfort zone or their cooler full of sports drinks and energy bars. It’s quite a contrast to the endurance races Wever creates, where most of the racers won’t even cross the finish line.

“If something happens out there during my race, you’re dead in the water,” Wever says. “But that’s one of the things my bikers are after.”

——————–

FAILURE BREEDS SUCCESS

The willingness to fail that some adventure athletes have seems counter-productive, but it could actually be the fastest, most consistent path to long-term success. There’s even a term for it: conscious incompetence—the act of making a conscious decision to let yourself try things you know you can’t do for the sole purpose of learning how to do it better.

“When I first started mountain biking, I was told that if I wasn’t crashing, I wasn’t trying,” Wever says. “You try, you crash, you learn.”

Failure may be a four-letter word in our culture, but it yields a greater learning curve than success. Buckminster Fuller, a famous inventor of the early 20th century, said it best: “Humans have only learned through mistakes.”

Kristen Dieffenbach has researched Olympic athletes who have won numerous gold medals in an attempt to discern what makes them succeed while others flounder. To a large extent, what the studies have determined is that an athlete’s failures actually determine their future success.

“People try to protect themselves from failure, but failure isn’t the problem,” Dieffenbach says. “It’s how you interpret that failure. Most people take it personally and see the failure as a sign that they’re a bad athlete. But the successful person looks at failure and says, ‘That wasn’t me as a person. That was a choice I made. A really bad choice.’ People who are successful, and that doesn’t always mean winning—whether in business or academics or sports—are resilient. They’re willing to challenge themselves to the point of failure. And they often do fail, but they pick themselves back up.”

To put it bluntly, in order to succeed, you have to be good at failure.

“Every time you get through some terrible mistake, you realize it wasn’t that bad,” Rich Dillen says. During a 100-mile race in Georgia in the middle of August, Dillen didn’t like the sports drink he had filled his bottle with at the aid station, so he poured it out. Then he realized that he didn’t have anything else to drink, and he still had another 20 miles to go to the next checkpoint.

“It was so hot, people were lying down in creeks to lower their body temperature,” Dillen says. “But I kept pedaling, and what I found out was I could go 20 miles in the middle of August without any water. It wasn’t a big deal at all.”

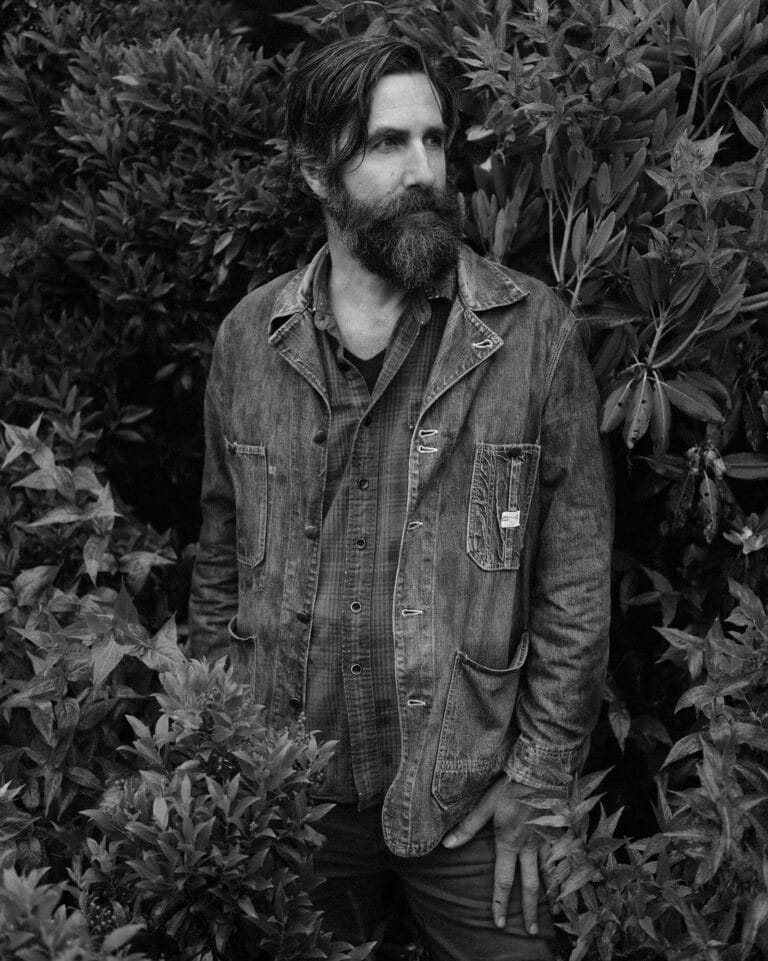

Nobody in the adventure sports world is better at failure than Rich Dillen. The Charlotte-based mountain biker rides his rigid singlespeed in 100-mile single day races and multi-day events all over the world, and more often than not, wins them. He was the first singlespeed across the finish line at the Pacific Traverse in Canada and the Off Road Assault on Mount Mitchell, and he was the first fixed-gear bike at the Shenandoah Mountain 100. He was even the 24-hour Solo Singlespeed World Champion in 2006. So the guy knows winning. But if Dillen is famous for one thing, it’s making really great mistakes. He writes a popular blog that discusses in detail how most of his races go terribly wrong, and ultimately, how he gets over those mistakes.

“Some of my best moments have been running down a mountain after having two flats with only one spare tube, or running out of water, or riding too far without food,” Dillen says. “I’ve even done the Pisgah Mountain Bike Adventure Race in the illogical direction, just to see how bad it could get. When things fall through the cracks and the race goes wrong, the experience is so much better. You get the chance to find out who you really are.”