Match to the Heart: A winter campfire with childhood friends provides enduring warmth.

For most of my childhood, my three cousins and I ran wild together—exploring the pathless woods, swimming in squishy-bottomed ponds, and chasing each other through the forest in late-night bottle rocket wars.

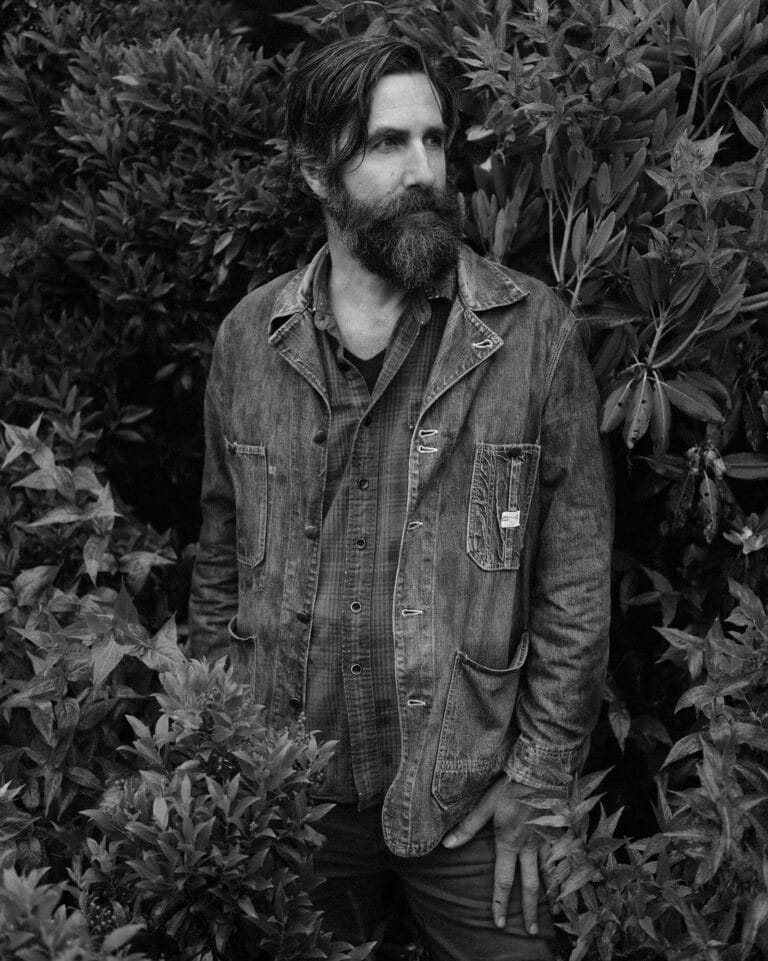

Now we are in our thirties, and we rarely cross paths. Jobs have separated us geographically; kids have consumed our free time. We traded our twenties for steady work and stable families. We were content, but we each harbored a twinge of nostalgia for our youth. So last month, we vowed to meet up for an overnight hike. It was an excuse to sit around a campfire together and remember the kids we used to be.

We arrived at the empty trailhead. Two days of rain had turned the trail into a brown slushie, and the swollen creeks chattered in between the silence of our single-file hike. My cousin Ben led us along the undulating, underwater trail.

“Does your dad still sleep naked?” I asked.

“T-shirt and no underwear. Boxers are too confining.”

Ben’s younger brother, Ryan, brought his dog—a white Great Pyrenees mammoth—who carried a lopsided saddlebag of water.

Mike, the oldest brother, was about to turn 40. As we slopped through the icy mud, he talked about his son’s little league.

“Catchers don’t have the arm yet to throw anyone out. A walk is a triple. Fortunately there’s a five-run rule.”

Ben, a hard-working, soft-spoken tax accountant, had organized the hike. He checked his watch to make sure we arrived at the campsite an hour before sundown, allowing us ample time to gather firewood.

“Where’s the gorp?” Ryan asked as we unloaded our backpacks. Ben produced a double-bagged sack: dried berries and raisins in one bag, peanuts and almonds in a separate one below it.

“Can I mix them together, or should I keep them separate?” Ryan asked.

“Maybe keep them separate,” Ben replied.

We gathered armfuls of wet, soggy limbs from the waterlogged woods. Ryan clipped a tuft of his dog’s shaggy fur for tinder. We struck a match, lit the fur, and placed it beneath the wet sticks. The fire smoked and fizzed but finally caught.

Temperatures quickly dropped below freezing after sunset. We thawed our frozen feet beside the fire, occasionally overcooking our skin and smoldering our socks.

Ben boiled water, then passed around freeze-dried meals, doling out spoonfuls of crunchy chicken and rice from a plastic pouch. We sat around the campfire and listened to coyotes howl.

“I’m too lazy to hang our food tonight,” Ben said.

“The coyotes can have this freeze-dried crap if they want it,” said Mike.

“We should probably pack up the gorp, though,” Ryan added. “We wouldn’t want the coyotes to mix up the nuts and berries.”

Mike got up to pee. The rest of us stared at the dancing flames.

Why were we mesmerized by fire? Ryan suggested a campfire was like a television in the room; our eyes are instinctively drawn to it like motion on the screen. Ben believed it was something more primeval: an ancient attraction imprinted on our DNA.

“Wow,” Mike said suddenly. He was standing at the edge of the woods, looking up at a glittering night sky. We all stopped talking and looked up. We hadn’t seen this many stars since our childhood summers together, when we dangled our bare feet off a dock, cast a fishing line into a quiet lake, and watched for shooting stars.

Now those grown-up kids sat in stunned silence once more, staring up at the sparkling sky. The campfire popped. Starlight warmed our frozen cheeks.

“Hey Mike,” Ryan said. “Your balls are still hanging out.”

The fire began to fade, and we headed to our tents. I couldn’t fall asleep. My cousins’ chorus of snores was interrupted by distant coyote yips. So I dragged my sleeping bag out under the stars and watched the constellations wheel across the sky.

Showers of sparks floated skyward from the campfire, until the firebrands were indistinguishable from the galactic nightlights overhead. I glanced from the fire to the stars and back to the fire again. Though we lived in climate-controlled boxes back in the big city, we modern hominids were still utterly dependent on primordial fire—whether it was a smoky campfire or the fiery orange ball that already tinted the eastern horizon.

An hour later, we mustered a meager fire from the glowing ash. Groggy and hungover, Ben heated water for coffee.

“Why do we torture ourselves like this?” he asked. “What makes grown men leave the comfort of their homes for a sleepless night in the cold woods?”

“I need to unplug,” Mike said. “To disconnect from the digital world and reconnect to the real one.”

“I also think there’s some guilt about how unnecessarily complex and comfortable our everyday lives are,” Ryan said. “We forget that all we really need are food, water, and warmth.”

And each other.

I probably won’t see my cousins for awhile. We’ll go back to our work routines and forget about living simply. But I’ll remember the astonishing, star-filled sky that silenced us in a moment of childlike wonder. And I’ll remember our campfire. I carry its glowing coals in my chest pocket, warming me on cold, starless nights in the city.