My world is a donut…a donut with an ever-expanding inner circle. It’s a tough concept to grasp as I’m thirty feet up a granite wall, half way through a rock climb on Rumbling Bald’s Cereal Buttress in Western North Carolina. The route is just outside my climbing grade, which is why I keep trying to convince myself of the whole “donut” thing. It’s a metaphor for learning that climbing guru Arno Ilgner uses with his students. The inner circle of the donut is your comfort zone—the climbs you know you can do. The outer circle is the “risk zone”—the climbs you don’t know you can do. The idea is to expand the inner circle by gradually climbing above your grade. Only my inner circle is not expanding. At the moment, it’s shrinking.

I’m not a good climber. I wouldn’t even call myself average. To call myself average would be an insult to average climbers. I love the sport, but I have too many mental hang-ups to truly excel into “average-dom.” My hang-ups are extensive, ranging from the typical (fear of falling) to the less tangible (fear of failure) to the irrational (fear that my belayer secretly hates me and is looking for an excuse to let me dirt). Physically, I think I have what it takes to become a decent climber, but internally I am a great ball of mental blocks. So I consulted the climbing guru, Arno Ilgner, creator of The Warrior’s Way, a mental training program that has helped thousands of climbers get past their fears. Ilgner’s process has even been endorsed by the reigning “king of the rock” Chris Sharma.

I have no delusions of ever becoming a Chris Sharma. Realistically, I don’t even think I’m ever going to become an Angie—the chick at my local climbing gym who likes to watch me struggle on easy bouldering problems, then sends them without breaking a sweat. I just want to get out of the kiddie zone and climb harder routes.

———-

The Guru

“There’s no cheating in climbing,” Arno Ilgner says. “Every inch is based on your effort. There are no free lunches.”

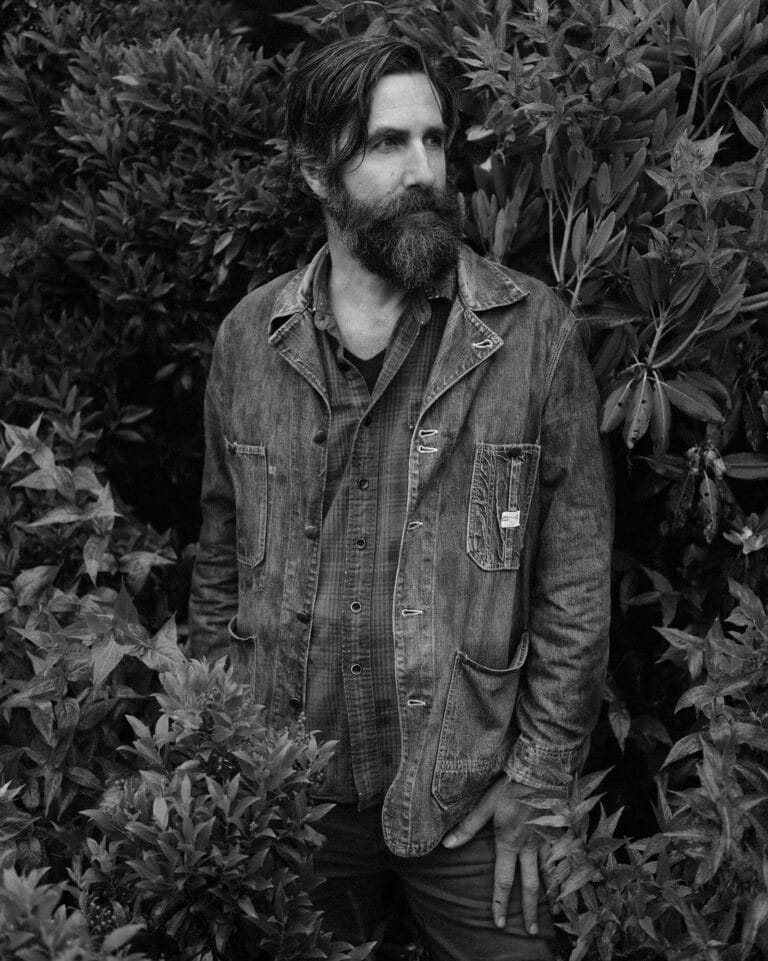

Ilgner has been climbing for more than 30 years. During the ‘70s and ‘80s, he helped develop classic Southern crags like Whiteside and Looking Glass. Today, he’s a middle-aged, hard-man climber living in La Vergne, Tenn., who likes to quote Taoist wisdom (“happiness is breathing”) and say things like, “You can’t know something until you go through the process of knowing it.”

Ilgner certainly has found this guru path honestly. After a stint in the military and a series of low-satisfaction jobs, Ilgner studied his way out of a mid-life crisis, researching how humans, from Buddhists to soldiers, respond to fear. Over several years during the ‘90s, Ilgner developed a mental training program for climbers that emphasizes “intelligent risk taking.” Instead of coming out of his mid-life crisis with a convertible and a girlfriend half his age, Ilgner emerged with the Desiderata Institute, a center where climbers learn The Warrior’s Way—Ilgner’s process for coping with fear—and a popular book on the subject, The Rock Warrior’s Way, which has been endorsed by climbing heavyweights Chris Sharma and Beth Rodden.

“Why are some climbers afraid when others aren’t?” Ilgner asks. “Even though fear has played a large role in climbing since the beginning, there wasn’t a lot of material out there that addressed it when I was developing The Warrior’s Way.”

One of the fundamental tenets of Ilgner’s program is that our brains lie to us.

“Our mind does not want stress. It wants to control the situation, the climb, and it will sabotage the process in order to gain control,” Ilgner says. “There’s a struggle between the mind’s conception of how the climbing needs to be done, and how the body knows the climbing needs to be done.”

According to Ilgner, the mind feeds the body false information in order to avoid the stress of a difficult climb. For a climber to move past his own fears, he must ignore his mind and trust his body instead. It’s a theory that manifests itself in The Warrior’s Way’s guiding principle: “When you rest, rest. When you climb, climb.”

It sounds simple, but the underlying factor holding most climbers back from their potential is that we can’t differentiate between resting and climbing. Most of us climb slowly, constantly reassessing the route and doubting ourselves throughout the climb. The Warrior’s Way prompts climbers to assess the risk of the climb intelligently at the base of the route: analyzing the series of moves the climb requires, the protection along the route, the potential fall. But once the decision to climb is made, climbers should move past risk assessment and simply climb, focusing attention on their bodies, not the potential pitfalls that may or may not occur along the route.

“Fear, which keeps us frozen in inaction, is the result of a lack of attention in the moment,” Ilgner says. “If you’re focused on your body, on the processes it takes to climb, there is no space for fear.”

———-

Be Here Now

Frozen against the wall at Rumbling Bald, I’m still thinking about the millions of things that could go wrong: falling, cracking my skull against the rock, ripping the skin from my fingers.

If Ilgner were belaying me, he’d tell me to push those thoughts out of my head and concentrate on my breathing. He’d tell me to be more self-aware.

“When you notice thoughts coming up that are sabotaging the process, let them go and refocus attention on your body,” Ilgner says. “It’s a continual process throughout the climb. All mental training is, is identifying where you want to focus your attention and redirecting that focus when you get distracted.”

The Warrior’s Way is Ilgner’s seven-step process (see sidebar below) for helping climbers move past the distractions of fear and focus attention on the body. I don’t remember any of it on my climb at Rumbling Bald, which ends after several failed attempts at the crux halfway up the wall.

Two days later, not wanting to give up on The Warrior’s Way, I head for a more controlled environment: the climbing gym. I’m immediately soothed by the candy-colored holds and the Beatles album pumping through the speaker system. I climb in the gym for the same reasons other people climb in the gym: it’s convenient and it’s air conditioned. The gym is well within my comfort zone, even though I’ve only ticked off the easiest problems it offers.

Ilgner’s students practice climbing faster than normal, or climbing with ear plugs, or climbing in shoes that are too big, or climbing without a chalk bag. Each exercise is designed to address a specific problem area (focus, expectations, ego), but they all work to expand your donut’s inner circle. The exercises that Ilgner teaches get you outside of your comfort zone whether you’re halfway up Looking Glass or bouldering in a climbing gym.

What I want to do is take the seven processes of The Warrior’s Way and send some of the hardest problems in the gym’s “cave,” but Ilgner has warned me of setting too high a priority on “finish line” goals like climbing harder routes.

“End goals are important, but climbers should focus more on making ‘process’ goals the primary objective. The processes—breathing, moving, resting—comprise the guts of a climber’s life and experience. You want to focus on those processes and enjoy them so you’re not just living for some vague experience in the future.”

So I’m starting from scratch with an approach that emphasizes attention on the body instead of one that centers around finishing a route. To do this, I need to climb easy grades faster than normal while I focus on my breathing. According to The Warrior’s Way, breathing is what connects the mind to the body. Concentrate on your breathing, and you can’t focus on your fears.

The goal of all this training is to enter the “flow state” while climbing. You’ve seen climbers in the flow state—they move quickly and effortlessly, gliding through the route with the grace of a monkey in the trees.

“It’s not magical,” Ilgner says. “The flow state is nothing more than paying attention to each moment, from one move into the next.”

Eager to enter the flow state, I approach an easy problem I’ve sent half a dozen times. It’s a sit start on a vertical pitch that gradually becomes overhanging the farther you get from the crash pad. It ends with a narrow roof about 12 feet off the ground. Easy, but fun. I take several deep breaths before I start, trying to focus on the air expanding my lungs. I keep this up for exactly two moves before I forget my breathing altogether and climb like I always climb: full of awkward pauses and maximum effort. I send the route, but I’m not happy with the climb, so I do it again. This time, I think all the moves through beforehand, rehearsing the motions on the ground so I don’t have to pause and think about them while I’m on the wall. I plan my single decision point—a stance where I can rest on the wall without exerting much effort and assess the rest of the climb—and convince myself to climb continuously to that point, rest, then climb continuously to the end of the route.

When you’re resting, rest. When you’re climbing, climb.

I sit on the crash pad and stick my rubber soles to the wall and start climbing, moving quickly from one move to the next. My breathing is short and choppy, but I’m climbing a little faster than normal and it feels fluid and comfortable. I pause once, resting exactly where I planned to rest, then finish the climb in about half the time it usually takes.

I let go of the last hold and drop to the crash pad with a soft thud, realizing that I didn’t worry once about falling, or my bad shoulder, or the lack of chalk on my hands. I didn’t really think at all. I just climbed.

<div style=”border:1px solid #0066CC; padding:10px;”>The Warrior’s Way

The Warrior’s Way can be summed up in the simple philosophy: “When you rest, rest. When you climb, climb.”

Here is the seven-point process that Ilgner teaches:

1. BECOME CONSCIOUS

Become aware of the mind’s tendencies to project unnecessary doubt and fear.

2. BE SUBTLE

Pay more attention to subtleties like the ego, posture, and breathing.

3. ACCEPT RESPONSIBILITY

Accept the situation like it is. Don’t wish the climb was easier or different. Accept it and collect accurate information.

4. GIVE

Instead of focusing on what you can get out of the climb, focus on what you can give to the climb to help you through the challenge. This enables you to create a plan of action.

5. DECIDE

You don’t want to commit to climbing if you’re going to get hurt or if it’s going to scare you so bad you won’t want to climb again. Weigh the consequences against past experiences. An appropriate learning situation is just outside your comfort zone. Push too far, and you’ll shut down the learning process.

6. BE RECEPTIVE

Trust the process and the climb and be open to modifying yourself to the situation. Instead of wanting to control the climb and change it to what you prefer, adapt to what the climb is requiring.

7. BE PRESENT

Value the process of the journey over the end result, which will enable you to focus your attention in the moment.</div>