Mountain bikers and wilderness advocates came together to protect 115,000 acres of Shenandoah Mountain.

Is there really enough room in the woods for everyone? A dispatch from deep in the weeds of a generation-long effort to protect Shenandoah Mountain.

In the summer of 2002, Lynn Cameron stepped nervously into Shenandoah Bicycle Company in downtown Harrisonburg. Involved in wilderness advocacy in Virginia since the late ’80s, Cameron had an ambitious plan in mind: having more land designated as wilderness on Shenandoah Mountain. The 70-mile ridge in the George Washington National Forest (GWNF) forms the western skyline of much of the Shenandoah Valley; among its many treasures is the 29,000-acre Little River Roadless Area, the largest roadless stretch of public land east of the Mississippi.

Thomas Jenkins, the owner of the bike shop, also loved Shenandoah Mountain and had been biking in the GWNF ever since a love-at-first-sight ride in 1989. Some years before Cameron’s visit, the Forest Service had bulldozed some singletrack on the mountain to create a fire line. Jenkins realized that the forest can’t protect itself, and helped turn him into a more outspoken advocate for preservation.

At the same time, federal law prohibits biking in wilderness areas, making the topic a wedge issue between hikers and bikers. And so, Cameron wasn’t sure how Jenkins would respond. Could the two sides, she asked, find common cause in the effort to keep Shenandoah Mountain wild?

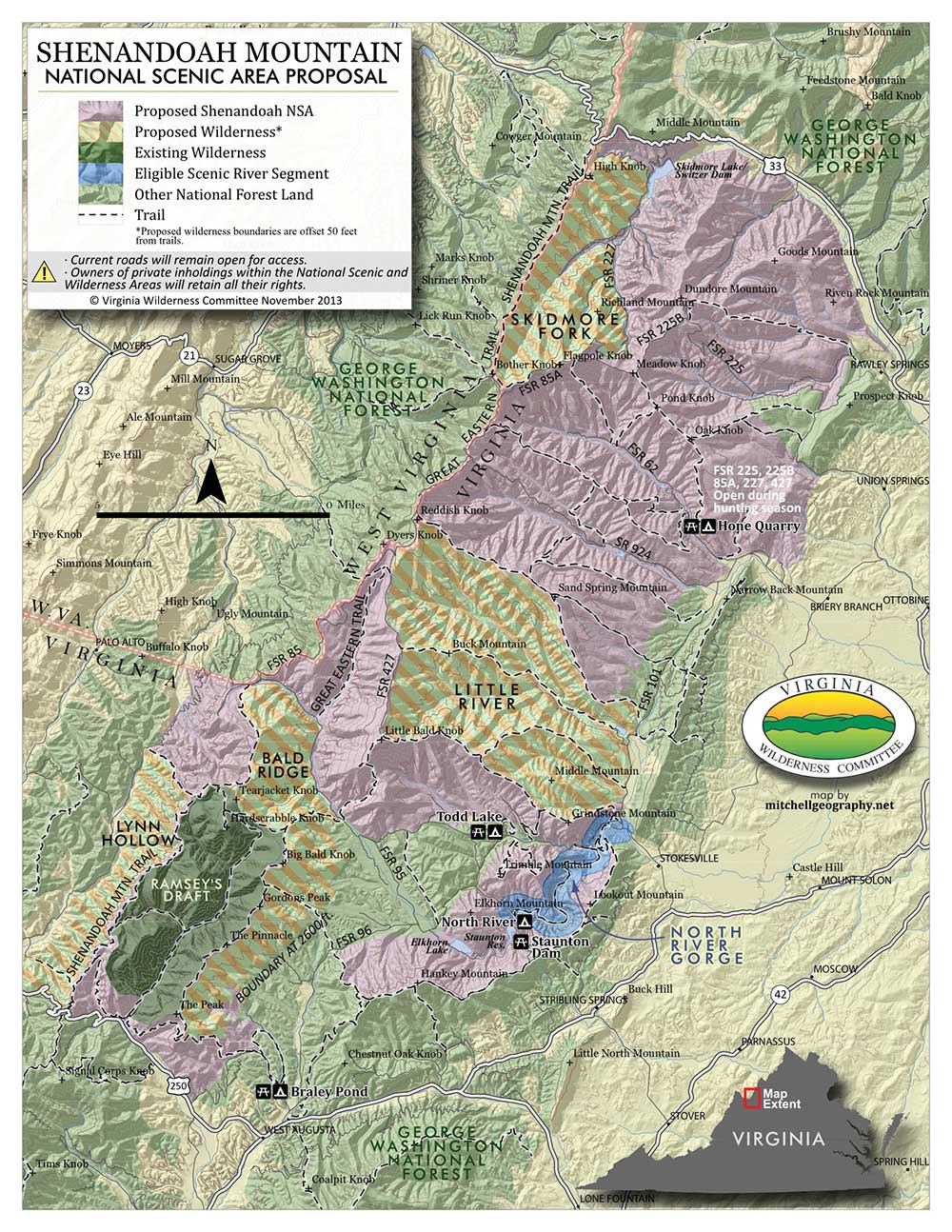

Their conversation that day led to the formation of a coalition of bikers and wilderness advocates that began meeting regularly. By 2004, the group agreed on a plan known as the Shenandoah Mountain Proposal, and formed a new organization called Friends of Shenandoah Mountain to champion it. The proposal called for the creation of a 115,000-acre Shenandoah Mountain National Scenic Area (NSA), with several new wilderness areas embedded in it.

The bikers agreed to support wilderness designations that would keep them off two major trails they previously rode. The wilderness people agreed to support a boundary adjustment to an existing wilderness area that newly opened several miles of the Shenandoah Mountain Trail to bikes, and kept their wilderness “ask” in the Little River Roadless Area to just 12,600 of its 29,000 acres.

“Compromise is hard,” says Cameron. “I remember how hard it was to make that decision.”

Still, the plan represented major progress, on paper at least, by permanently protecting a huge swath of Shenandoah Mountain from development. It included new wilderness on some of its most remote bits, and would accommodate biking throughout the rest of the NSA, a designation with much more flexibility than allowed by the federal Wilderness Act.

“Each side had a lot to give and a lot to lose, but they were willing to do that,” recalls Jenkins. “That’s the beauty of this agreement. It’s all just to protect Shenandoah Mountain.”

Jenkins remains troubled by the entire premise of a wilderness area and its blanket ban of biking. “But I can’t let that cloud my judgment about what I think is best for this area,” he says.

After finally signing the Shenandoah Mountain Proposal one day at the public library in Harrisonburg, the entire group went across the street for a round of celebratory drinks. Still, they knew their work was far from done. Creating an NSA requires federal legislation, with many tricky boxes to check along the way – especially given that the Shenandoah Mountain NSA would be the largest permanently protected piece of national forest land east of the Mississippi. And while much has happened in the decade and a half since, Congressional approval still looks to be years away.

In 2007, the Forest Service began revising the GWNF management plan, giving Friends of Shenandoah Mountain an opportunity to have their proposal formally written into it – another key step toward realizing their goals. The plan revision, however, became an arduous process. In 2010, unhappy with the options they’d been presented so far, a group of forest users far more diverse than Friends of Shenandoah Mountain began meeting amongst themselves, searching for common ground and driven by a conviction that the 1.1 million-acre GWNF was big enough for all of them. What emerged became known as the GWNF Stakeholder Collaborative, including bikers and hikers who represented a “preservation” faction, plus “active management” advocates like hunters, fishermen and the timber industry

“That’s unusual. We kind of threw everything into the pot,” says Mark Miller, executive director of the Virginia Wilderness Society. “[We said], ‘instead of arguing, let’s create a win-win where everybody gets some of what they want.’”

While the preservationists worry about things like fracking on Shenandoah Mountain, active management advocates have long been concerned that there’s too little human intervention on the GWNF.

“There’s a lot of wildlife species that are in decline, some in significant decline, that require early successional forest habitat,” says Al Bourgeois, a biologist recently retired after 29 years with the Virginia Department of Game and Inland Fisheries.

Maintaining wildlife clearings are one way of accomplishing that. Timber sales are another, and align precisely with the goals of the logging industry, another group represented on the GWNF Stakeholder Collaborative.

While the group remained committed to the general concept that the forest was big enough for all of them, hashing out the details was tricky at times. Where, exactly, on Shenandoah Mountain could the wilderness folks stomach timber sales? And where would the timber industry support new wilderness areas from which it would be permanently excluded?

At some points, Cameron says, it felt as if the stakeholders’ differing priorities were too great to bridge. But slowly, they inched toward agreement.

“We insisted that we wanted to listen to each other,” she says.

A field trip to Mud Pond near the northern edge of the proposed NSA stands out in her memory. At one specific spot in the road, the preservationists stopped to admire a looming stretch of mature forest; on the other side was a stretch of early successional habitat that the active managers desperately want more of.

“It was a moment where we realized we can both be happy,” Cameron recalls.

As a result of the group’s work, Friends of Shenandoah Mountain whittled its proposed NSA from 115,000 acres down to 90,000 acres. On the roughly 25,000 acres carved out from the original proposal, the preservation faction supports increased timber sales, burning, and other management that serves the interests of other stakeholders.

In the end, with the support of the entire stakeholder group, that amended version of the Shenandoah Mountain Proposal was included in the GWNF management plan that was finalized in 2014 (albeit with a few differences, including reduced wilderness acreage).

While having more actively managed forest land around the proposed NSA was key to the entire stakeholder group’s support of preserving the rest of it, actually planning and overseeing that work falls to the Forest Service. Now, thanks to a number of converging factors, some stakeholders worry that the large-scale active management projects they’d envisioned around the NSA might not happen – potentially jeopardizing their entire grand bargain.

“As our capacity and priorities change over time, [GWNF] leadership must continually revise our program of work to equitably focus resources across the combined George Washington and Jefferson National Forest land areas,” wrote North River District Ranger Mary Yonce, in an email. “This reflects the Forest Service’s need to respond to increasing public demand for recreation, increasing need for vegetation management, aging infrastructure, and decreasing capacity across the forest. This does not diminish the importance of achieving Forest Plan objectives in the vicinity of the proposed Shenandoah Mountain NSA, nor the importance of the Stakeholders’ strong advocacy for healthy public lands.”

Bourgeois, one of the active management proponents in the stakeholder group, says it’s a “tough question” as to whether the whole group would continue to support the Shenandoah Mountain NSA.

“We’re continuing to work with [the Forest Service] to see how we can get active management done,” he says. “I do not want to paint the Forest Service here as the bad guy because they’re not … There’s things beyond their control that are keeping them from [doing more].”

One is money. In the current fiscal year, the George Washington and Jefferson National Forest (the two forests were administratively combined in the ‘90s) has a budget of $21.8 million, a 29 percent decrease from a decade earlier. Another is near-total turnover among leadership since stakeholders began working alongside the GWNF during its management plan revision.

“We’ve had a vision for how we thought things should move forward,” says Miller. “Where we missed the boat is when agency staff turnover occurred, we didn’t do a really good job of articulating the vision.”

In late June, members of the GWNF Stakeholder Collaborative – which is being facilitated by The Nature Conservancy – met with the Forest Service to discuss their concerns about the lack of management work being planned for Shenandoah Mountain. According to Miller, it was a productive meeting.

“We talked about priorities for the Forest Service and how we as a group might be able to assist the agency in meeting the goals of the forest plan,” he says. “It was an open frank discussion, [and] we agreed to meet again in a few months.”

And Bourgeois says he remains committed to seeing the plan move forward in a way that everyone can live with.

“It’s not easily solved, but that’s why we’re working together on it,” he says.

In the meantime, Cameron continues working on securing the support of several local governments in Virginia directly affected by the proposed NSA. It’s a step that’s generally another prerequisite for eventual Congressional action. On June 26, the Augusta County Board of Supervisors passed a resolution of support for the Shenandoah Mountain NSA, and Cameron expects similar votes before long in neighboring counties.

It’s just one of the current obstacles to a plan that she and many others have been actively pursuing for coming up on two decades. Over that time, there’ve been major breakthroughs, hard choices and setbacks, and much is still up in the air. Who knows what the future holds; they won’t hazard a guess as to when their dream might become reality.

“It’s a crazy long process,” says Jenkins. “It’s going to be an incredible feat if it can get all the way to the act of signing on the dotted line with everyone being satisfied.”

Thrilled is probably too high of a bar, he says, when it comes to this many different groups and their different visions of an ideal outcome. Compromise has been and surely will continue to be key. But one thing that’s for sure at this point, Cameron says, is that they wouldn’t have even gotten this far without everybody giving a little in search of a greater common good.

“Over time, I was able to see the point of view of others more clearly, and recognize the value of working together,” Cameron says. “Now that I’ve been through 15 years of advocating for [the Shenandoah Mountain NSA], I realize how helpful those compromises are.”

As a result of the group’s work, Friends of Shenandoah Mountain whittled its proposed NSA from 115,000 acres down to 90,000 acres. On the roughly 25,000 acres carved out from the original proposal, the preservation faction supports increased timber sales, burning and other management that serves the interests of other stakeholders.