Most of us don’t know. Here’s a quick guide to the health of the water you paddle, fish, swim, and drink.

Kentucky’s Stoney Fork isn’t supposed to run an otherworldly shade of translucent red, but that’s what Matt Hepler found in late March last year. Hepler, a water scientist, says the color was due to an upstream storage tank leaking potassium permanganate, a chemical used in treating acid mine drainage. Hepler’s photos of the discolored creek went viral on social media.

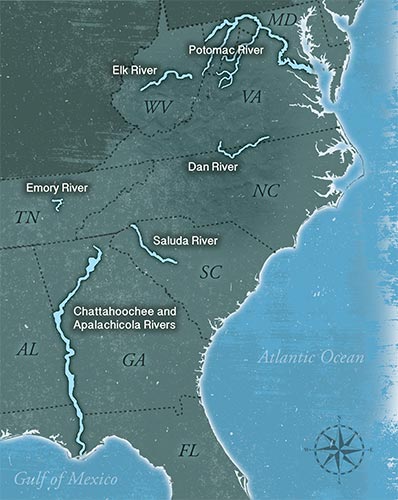

The spill wasn’t an isolated case for Appalachian rivers. As many as 10,000 gallons of chemicals leaked into West Virginia’s Elk River in 2014, leaving a quarter million people without potable water. Just six years earlier, millions of cubic yards of coal ash flooded the mouth of the Emory River in Kingston, Tenn.

Those incidents all pose fundamental questions about the health of our waterways, but diving deeper into their answers often means descending into a maddening blend of jargon and legalese. Terms like 303(d) impairment and Section 319 funding all complicate an easy understanding of issues that have impacts on each of us. What’s really happening to our rivers, and how do those issues affect the millions of people across the Blue Ridge who rely on them for drinking water and as places to swim, paddle, or fish?

We Are What We Drink

“Every aspect of what we do in our daily lives affects our water quality,” says Stephanie Kreps, a water manager with the Virginia Department of Environmental Quality. The host of threats to water quality is so pervasive that it’s virtually impossible to find a major watershed anywhere across the Blue Ridge that doesn’t have at least some of its streams suffering from water quality impairments.

Headline-grabbing incidents like the 2014 Elk River spill justifiably dominate our public dialogue about water quality, but less-visible issues like sediment and bacteria are often even more dangerous. These types of pollution often stem from “non-point” sources, a regulatory term meaning that they cannot be traced to a single location like a pipe or the site of an accidental spill. Instead, any number of sources dispersed across thousands of square miles of land can all contribute pollutants to the same waterway.

In Southern Appalachia, disturbed lands for development, logging, and surface mines expose large amounts of sediment that can eventually make its way into nearby rivers. It’s more than just runoff; the increased sediment load causes higher concentrations of salt and selenium downstream of mining activities. A 2017 Duke University study showed that several streams impacted by mountaintop removal mining in West Virginia now run consistently saltier for up to 80 percent of the year.

While elevated sediment and salinity levels may sound like a minor issue, they can spell huge problems for the overall stability of the stream ecosystem. Those impacts often show up first in animals like aquatic insects that thrive along the stream bottom, creating ripple effects throughout the stream’s food web, all the way up to fish populations.

In other cases, excess levels of contaminants like selenium can cause different problems altogether. A 2010 study of West Virginia’s Mud River watershed found physical deformities in a number of fish species—including game fish like bluegill and largemouth bass—as a result of selenium toxicity.

Then the hard work of addressing those sources of pollutants begins. “How are we going to fix this?” Kreps asks. That question is answered through the development of an implementation plan, where Kreps says state and federal agencies work with nonprofits, community members, and other stakeholders to draft a blueprint for reversing a stream’s pollution issues. It’s a process that may take years, but it’s a key step in securing the financial resources needed to help communities address polluted streams.

Up Sh*t Creek

Upper Tennessee River Roundtable Executive Director Carol Doss has spent much of her time in recent years grappling with another nonpoint source pollutant: bacteria. The cause of bacterial problems in most streams is fecal coliform contamination, the scientific term for bacteria that originate in the large intestines of warm-blooded animals. The proverbial bear shitting in the woods can be a source of fecal coliform issues, but problems really begin when human waste enters the picture.

Doss mentions that unmaintained septic systems and pet or livestock waste are major sources of fecal coliform bacteria in regional streams. “I think it’s something people don’t think a lot about,” Doss says, but without appropriate control measures, “it’s going to get into the water somewhere.”

Among the cocktail of pathogens commonly found in fecal coliform contamination is E. coli, which can cause gastrointestinal illness in swimmers, boaters, and other users that might accidentally ingest untreated water. In other cases, viral pathogens like those causing hepatitis can even hitchhike with the bacteria found in untreated sewage, further enhancing public health threats.

Many areas have programs that help landowners repair failing septic systems or remediate erosion issues, but those projects can be time-consuming and expensive to complete, especially for low-income residents. Plus, nonpoint source issues can present communication hurdles since they are often not as visible as something like a pipe discharging wastewater into a stream. “With nonpoint sources coming from all over,” Doss says, “you don’t immediately know where (pollutants) are coming from if you see them in a stream.”

Regulating a River

Regulating a River

By contrast, identifying and regulating those known locations—called point sources—is much more straightforward. That’s thanks in part to the Clean Water Act, a landmark environmental law that governs how both point and nonpoint sources are regulated.

While the law doesn’t prevent the release of contaminants into waterways outright, it does establish a licensing system that controls the amount of pollutants—everything from treated sewage to chemical waste to even water artificially warmed by industrial processes—that a facility can release into a waterbody. The resulting permits obtained by those facilities allow for regulators to track wastewater discharges and ensure that pollutant levels remain within the safe confines of regulatory standards.

Today, the number of permitted discharge facilities spread across the Blue Ridge numbers in the thousands, ranging from large facilities like the region’s power plants to mining outfalls and even the small wastewater treatment plants serving the region’s subdivisions and ski resorts.

The value of permitting point sources is that regulators can keep track of individual facilities and issue penalties for violations, but that doesn’t mean that those regulations are without controversy. As one example, communities across the Blue Ridge are currently embroiled in a long-term battle over the storage of coal ash—a chemical-laden residue that results from burning coal—in constructed ponds near waterways. Lawsuits and public outcry over coal ash disposal have raged in recent years, especially at coal ash ponds along the French Broad River, James River, and Potomac River.

These often-unlined storage leak toxic pollutants into waterways, aquifers, and drinking water sources. The Southern Environmental Law Center has been engaging in legal action related to coal ash across multiple Southeastern states, including filing a 2017 lawsuit against Duke Energy over its coal ash storage at a power plant near Charlotte, citing elevated levels of arsenic, mercury, and other toxic pollutants in waterways near the site.

Taking Action

Solving the region’s water quality challenges ultimately comes down to one thing: awareness. Doss’s organization, Upper Tennessee River Roundtable, works across the thousands of square miles to enhance public understanding of water quality threats. Doss says that people “just light up” once the acronyms and jargon surrounding water quality topics are broken down into real-world terms. “They want to help do something good for the environment,” she says.

Anglers and paddlers are especially important in providing input. A recent project led by recreational groups to develop a new put-in along one Virginia stream discovered a location where a nearby building was straight-piping untreated sewage directly into the waterway. “You can’t beat the local context of somebody who lives on the ground,” Kreps says.

And what about monitoring wastewater discharges or catching accidental spills like the one that discolored Kentucky’s Stoney Fork? Public awareness has a critical role to play there, too. Savage and Hepler both say that citizen involvement is a crucial step in identifying and addressing water quality violations. In fact, Hepler says that he originally became aware of problems with Stoney Fork while traveling to investigate a citizen complaint at a nearby stream.

Join a water monitoring group, or submit reports to your state’s environmental agency if you’re out on the river and see something that doesn’t look right. Even the small step of vocally supporting healthy rivers can empower others to action, says Erin Savage, program manager at Appalachian Voices. “Get the word out within your community that you are aware of water quality issues and you value clean, public water.”

Potomac River (West Virginia/Virginia/Maryland)

The Potomac was named the nation’s most endangered river in 2012 by nonprofit American Rivers due to pollution from agricultural and urban land uses. Ongoing issues with coal ash disposal are causing further concern within the Potomac watershed.

Chattahoochee and Apalachicola Rivers (Georgia/Alabama/Florida)

Increasing water demand and pollution from expanding suburban populations in the Atlanta area are putting a strain on wildlife and human populations downstream, triggering a decades-long legal battle among stakeholders.

Dan River (North Carolina/Virginia)

A February 2014 leak of an estimated 39,000 tons of coal ash entered the Dan River from a Duke Energy steam facility in Eden, North Carolina, causing concern about potential contamination from metals and other pollutants for miles downstream.

Elk River (West Virginia)

A 2014 chemical leak into the Elk River left several hundred thousand residents without drinking water and raised national awareness about the health of Appalachian streams.

Emory River (Tennessee)

A ruptured dike at a waste containment area near the confluence of the Emory and Clinch Rivers resulted in the largest release of coal ash in U.S. history in 2008.

Saluda River: (South Carolina)

The Saluda, which cascades off of the Blue Ridge into the South Carolina Piedmont, has been plagued by bacterial contamination in recent years. Several guides, outfitters, and other businesses filed a 2017 lawsuit against a regional utility provider, alleging a loss of business due to pollution in the river.

How You Can Actually Do Something About Water Quality?

KNOW your watershed

What stream does runoff from your community end up in? Is it safe to swim, fish, or float a nearby river? The USEPA’s How’s My Waterway? tool allows you to enter a zip code or town and receive info on the status of streams that are found nearby. https://watersgeo.epa.gov/mywaterway

Know your point sources

Concerned about what might be getting discharged into your favorite river? Most states keep searchable, online lists of permitted point sources. North Carolina has even assembled its permitted point sources into a map showing the location of each. https://deq.nc.gov/about/divisions/water-resources

Get active

Most major watersheds across the Blue Ridge have nonprofit organizations dedicated to preserving and improving the condition of nearby streams. Find and join your nearest watershed advocacy group to keep track of events in your area. Most organizations host regular public events such as stream cleanups or events to train citizens in water quality monitoring.