And the Real-life Canoe Trip that Spawned the Famous Story

Fifty years ago, a film appeared on the big screen which caused audiences to squirm with angst, due to a terrifying sequence of terrifying events in the backwoods of the Southern Appalachians. During production of Deliverance, three Georgia whitewater paddlers happened to be in the right place at the right time, becoming stuntmen and technical advisors for the film. Doug Woodward recounts what it was like to be part of that experience.

A question I’m often asked, when the conversation turns to the movie Deliverance, is “How real is that story? Did it arise from James Dickey’s imagination, or did it have its origins in real life?”

Yes, there was indeed a canoe trip into wild country that author Dickey and two friends took as young men. A journey with sinister undercurrents that could easily have taken the trio into a darker scenario.

“How real is that story? Did it arise from James Dickey’s imagination, or did it have its origins in real life?”

I met Dickey only once. It was on an intimate fall evening in Atlanta, at Lewis King’s Buckhead home. Dickey’s friend since their early twenties, King was, in many ways, the real-life model for Lewis Medlock (played by Burt Reynolds) of Deliverance. As a canoeist, archer, and athlete of note, he had already lived the role.

There were six of us at the table that night: King and his wife Joan, James Dickey, Payson Kennedy, Claude Terry, and myself. Payson, Claude, and I had been running whitewater rivers together for years, but it was Claude’s friendship with King that had brought us there.

Around the King dinner table, with rising excitement, we discussed logistics, equipment, and sets as if we were the filmmakers ourselves. The Chattooga was the river we all knew best: the rapids, the obscure access points, where to find the required scene. In the end, Warner Brothers chose both the Chattooga and Tallulah, each becoming a portion of Dickey’s fictitious Cahulawassee River.

Dickey was an imposing figure of a man, and his presence filled the room. But it was much more than physical. There was a mystique about him—of things hidden, perhaps ominous—that he enjoyed perpetuating. There were references to the canoe trip which he and King had taken years before with another close friend, Al Braselton. The trip that gave rise to the imaginings which would eventually become Deliverance. Dickey would not describe details of that canoe trip. With a knowing smile, he would simply say, “There’s a lot more truth in the story [Deliverance] than you might think.”

King was more candid. We knew that they had canoed the Coosawattee River in northwest Georgia. Truth now eerily imitating fiction, the Coosawattee, at the time of the Deliverance filming, was in the process of being dammed and the valley behind it would slowly fill over the next two years, drowning all traces of those whose lives were once intertwined with the river.

King later supplied what we came to regard as the facts of that river trip, now long faded into the mists of time. First, he had emphasized, “You may think of the southern Appalachians as being wilderness now, but in the thirties and forties that country was really wild. A man that was perceived as a threat to the mountain folk might just disappear—permanently. Murder was always a viable option, because few outsiders were going to go snooping around those forests looking for the missing man.”

It seemed that the canoeing that day was actually done by Dickey and Braselton, while King went looking for a place downstream where he could meet the pair. Finding no road to the river, he parked and started down a path leading through the woods. Like yellow jacket sentries guarding their nest against danger, two armed men suddenly appeared and demanded to know his business. King’s tale of a canoe on its way through the rapids of this river seemed absurd to the mountain men, and they thought it was far more likely that he was a revenue officer looking for their moonshine still. The older of the pair told the younger to take King to the river and “stay with him, son,” words—along with their sinister undertone and unspoken meaning—that King never forgot.

Unsure of his armed companion’s patience, and almost overwhelmed by the thought that Dickey and Braselton might already have passed that point, King waited and sweated and prayed. The canoeists had run into serious difficulties themselves in the rapids upstream, but finally hove into sight as daylight was beginning to dim. At that point, the demeanor of the mountain men changed completely. Shotguns disappeared, and there were smiles and kind words as they helped carry the canoe and gear up the hill to the truck.

We left the King home in high spirits, hoping against hope that we could become part of the adventure to come—the actual filming of Deliverance.

Waiting through spring and early summer was agonizing, but at last the Warner Brothers call came and we immediately put our Atlanta jobs on hold.

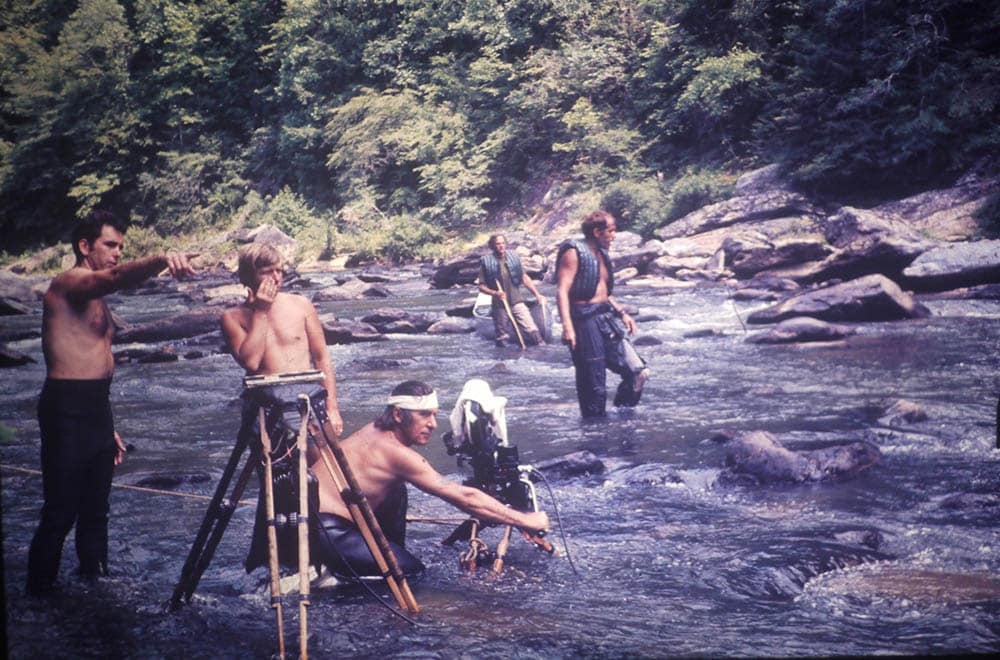

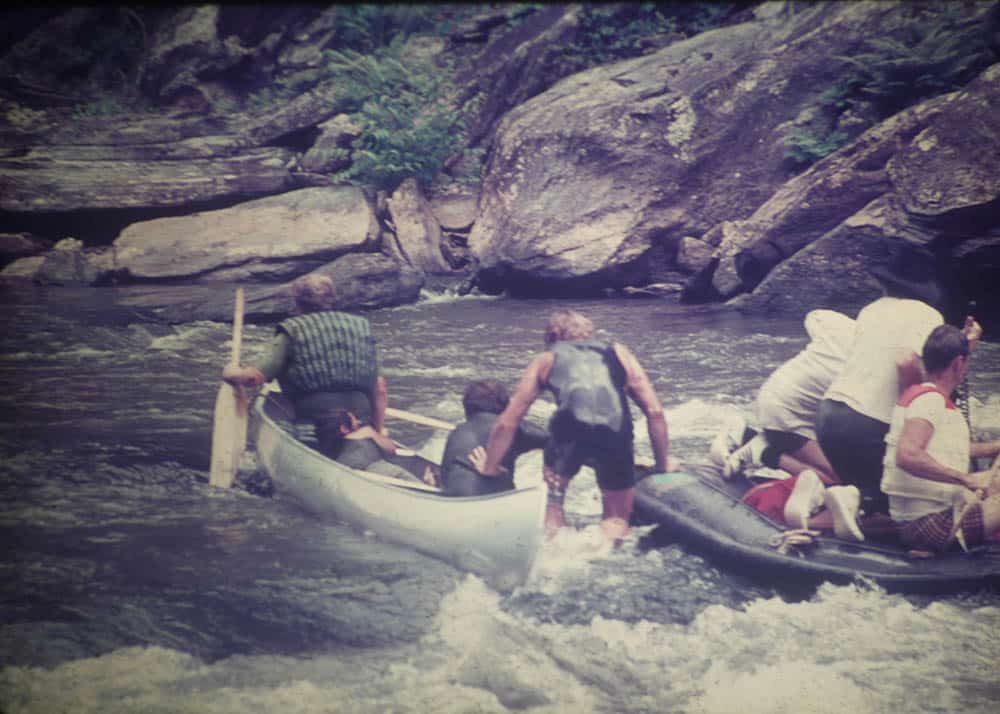

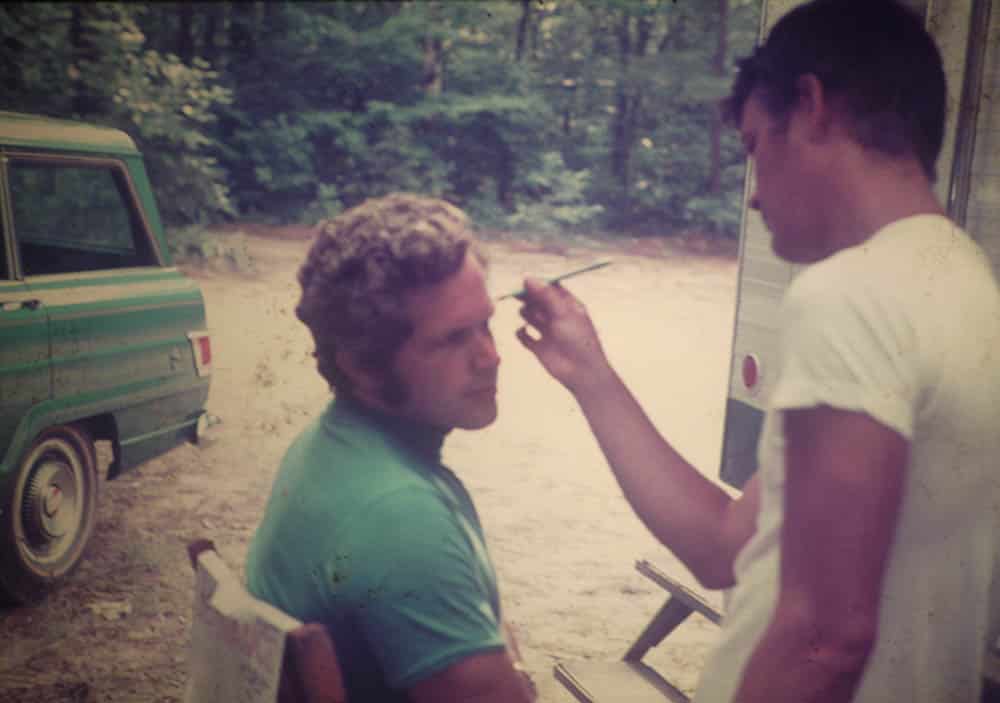

For two weeks, we were made up as doubles, including “cuts and bruises,” Claude as Jon Voight, Payson and I as Ned Beatty. Our canoeing was done primarily in the Five Falls section of the Chattooga, where the bruises we acquired were quite genuine. But instead of an injured Burt Reynolds lying in our canoe, we paddled with his dummy, affectionately known as “No Balls” for the void in his hinged crotch area. We were also consulted for certain scenes, such as Voight clawing for a finger hold on what would be named “Deliverance Rock.”

Our screen time could be measured in seconds, but the effect that the film had on our lives was far-reaching. That same summer, Claude and I started Southeastern Expeditions, running folks by raft down the Chattooga while still hanging onto our jobs in Atlanta. Payson and his family took an even bigger leap, as they broke all Atlanta ties and threw themselves into transforming the old Tote-N-Tarry Motel in Wesser, N.C. into one of the premier whitewater outfitters in the world, the Nantahala Outdoor Center.

Fifty years have passed since Boorman and his crew brought Dickey’s novel to life on the screen. For me, the old intensity is gone and now it’s just fun to get into it once in a while when someone happens to mention Deliverance. But sometimes I look back over all those years—how the three of us became linked to the legends of the film and the river, the whitewater rafting business that Claude and I founded, the evenings spent behind the projector as folks clamored for candid glimpses of Reynolds and Voight—and think to myself, if not for James Dickey…

Cover Photo: The Deliverance film crew gets ready to capture stunt work on Five Falls, a rapid on the Chattooga River. Photo by Doug Woodward