Has Alex Honnold’s free solo climb of El Capitan sparked more daredevils? At least one free soloist has fallen to his death since the film was released.

In 2017, the day after Alex Honnold completed his free-solo ascent of El-Capitan, climbing journalist and author Daniel Duane wrote in The New York Times: “I believe that it should be celebrated as one of the great athletic feats of any kind, ever.”

A National Geographic documentary film crew captured the four-hour 3,000 foot ropeless ascent—as well as the years of intense preparation Honnold put into climb. Released in theaters last fall, “Free Solo” won an Academy Award and grossed $21 million at the box office, making it the highest grossing National Geographic documentary of all time. A record-breaking 3.1 million viewers watched the premiere on the National Geographic Network.

The documentary attracted viewers outside of the climbing and extreme-sports community. The visceral and primal spectacle of witnessing a man face imminent death attracted a broad audience. Honnold, already a celebrity in the climbing world, became a household name.

It was an exercise in existential voyeurism, and freesoloing, the most taboo, dangerous and controversial styles of climbing, reached the mainstream vernacular.

Will all the current fanfare directed towards freesoloing cause a surge in climbers to leave their ropes and bolts behind? We asked members of the Southern Appalachian climbing community for their thoughts on freesoloing.

Austin Howell

“When the rope is off, you can’t afford to slip,” explains free solo climber Austin Howell. Austin Howell was a rock climber for 12 years, 10 of which had been primarily as a free-soloist. He was the kid that climbed the tallest tree in hide and seek never to be found. He took up rock climbing at an indoor gym in college. After college, he worked day jobs that called for him to climb 300-foot cell towers, often in harsh weather. He became a proficient lead climber, requiring him to go long stretches between safe points.

Unhooking the rope for the first time for Austin was not an epiphany; it was practical. He was half-way up a steep rock face, felt weighed down by the heavy bag of bolts and the ropes on his back, and simply unhooked himself and passed the gear to his climbing partner.

“Soloing in one way is the most obvious way in the universe,” he explained, speaking proudly of John Muir in 1888 climbing Cathedral Peak. “Essentially he free-soloed that cliff to the top of it, and free-soloed it back down.” For centuries, Pueblo people had built houses into the sides of tall cliffs without any safety devices. Carabiner and belays didn’t arrive until 1933.

“Subjectively there’s nothing safe about it. There’s risk and there’s consequence. The consequence is very obvious,” he said.

One month after talking with BRO, Howell, age 31, fell 80 feet to his death on a free solo climb at Linville Gorge.

Sasha DiGiulian

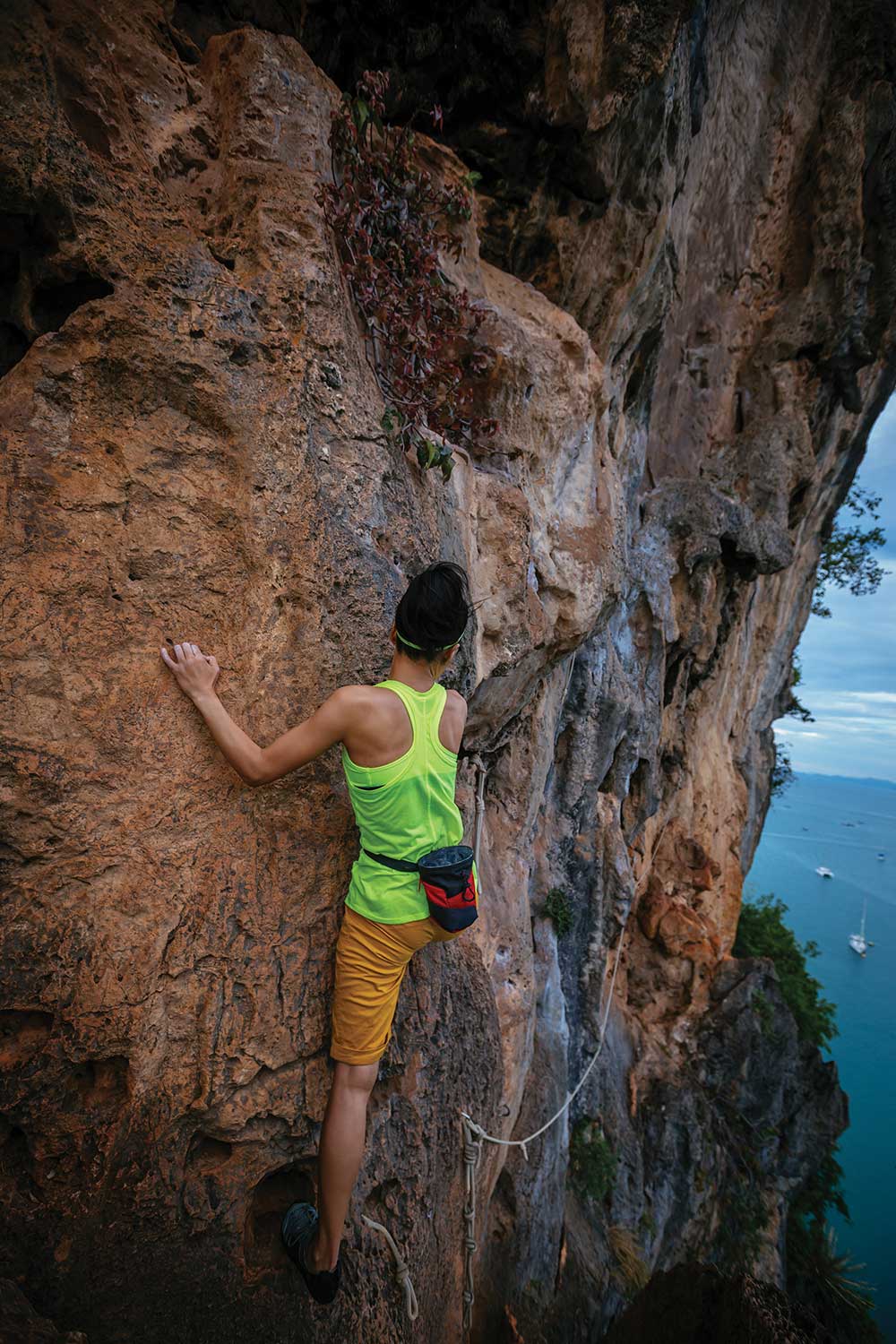

“I do not free solo,” says Sasha DiGuilian, a world-renowned professional climber from Virginia who spent much of her youth climbing in the Red River Gorge. “Rocks can break and incidences out of my own control can occur. To do this would be selfish to my family and my loved ones because I can handle my own death, but I would not want to put those close to me through the heavy weight of loss.”

The 26-year-old is known for her free climbs, different from free soloing, in which the climber may use climbing equipment only to protect against injury during falls and not to assist progress. In 2015, she became the first woman to free climb Magic Mushroom (7c+), one of the most difficult routes on the north face of the Eiger Mountain in Switzerland.

“If I am in a situation in which free soloing is the only option to reach the summit, and there is not a safer way, there will be an occasion that I may embark. However, it is not something that I seek out.”

Sasha DiGuilian on Free Solo: Sasha Digulian wrote this on Instagram the night Free Solo won the Academy Award for best documentary film.

“Last night Free Solo won an Oscar! First of all, huge congratulations to Jimmy Chinn, Alex Honnold, and all of the crew involved. Needless to say, an accomplishment of a lifetime and I know this came with a lot of hard work and perseverance. It is momentous for me to see a climbing film recognized at the highest of high regards.

With all the hype and attention that is sure to come from this, I felt it was important for me to speak about the very specific differences between this form of climbing (free soloing) and the approach the vast majority of climbers take to the sport itself.

What Alex does when free soloing is by nature, very risky. And while in my career I have had instances where a form of this has been necessary it has also been a choice that came as a last resort and has happened less than a handful of times over my 20 years of climbing.

Free soloing is a style of climbing that a very small percentage of climbers partake in as there is no higher level of risk: life or death. I say all this with the caveat that it is not the sole form of climbing that Alex does.

While I am so excited by the recognition this film has received, I also feel like I have spent a big portion of my career trying to educate people unfamiliar with climbing about our sport. A goal of mine has been to demonstrate that anyone can do it, and that it is a safe and welcoming activity.

In my opinion Alex is one of the greatest climbers of all time to have the capacity to realize all that he has accomplished. However, I also just want to make it clear, which I do feel like this film has done a good job of, the separation that free soloing has from the general form of climbing that I encourage all of you to experience at some point in your life. But when you do, especially if it your first time: please be sure to seek out guidance from a trained and knowledgeable climber at your local gym or local crag. Take a course in how to enter the spot safely and with the proper training and equipment.

This is an incredible and inclusive sport that, when approached correctly, is safe and fun for everyone.”

Jesse Anderson

Jesse Anderson, 32, has been a park ranger at Pilot Mountain State Park for six years and a climber for a dozen, but never as a free soloist.

“I understand the mantra with the connection, the rock, the silencing of the mind through free soloing, but it is not for me,” Anderson said. He hasn’t seen an uptick in free solo climbing on his watch at Pilot Mountain after the Honnold documentary.

“No matter the preparation, the unfortunate truth is that accidents happen, and that’s why people use ropes.”

The free soloist has the freedom to leave the ropes behind, but anyone else climbing the same crag that day has the unexpected risk of witnessing brazen climbing and potential loss of life.

“If a free soloist starts climbing beside another climbing party that is roped up, it is unsettling,” says climbing filmmaker and photographer Adam Nawroot. He noted how Jimmy Chin, producer and principal shooter of Free Solo (also an advanced climber and one of Howell’s close friends), chose in advance to pull the crew from the Huber Boulder Problem, the most risky climbing sequence of the ascent.

“The Boulder Problem is the single reason nobody had even considered free-soloing [the] Freerider [ascent of El Capitan],” Caldwell told Men’s Journal last year. “It took Alex almost a decade to get comfortable on it. Otherwise, he’d probably have free-soloed it in 2009.”

Chin and Honnold knew that if Honnold was going to fall, the Boulder Problem would be the most likely place, and Chin didn’t want a videographer to have to witness Honnold fall out of frame.

“If you’re a free-soloist and you show up at a crag and you start free soloing and don’t clear it with everyone they might watch you die right there. It is unfair to the other people around you.”

Zachary Bopp

Zachary Bopp agreed. He is the Outdoor Program Supervisor at REI in Chattanooga who leads climbing classes.

“When you encounter a free soloist on a crag, you do not know whether they have been dialing in the climb as Honnold did for El Capitan, or they just decided to do it with little or no forethought,” says Bopp. “It can be hard on other climbers as to whether they should speak up and say something. It is the most unsafe climbing there is, especially coming from an instructor background,” says Bopp.

“We set ground rules from the get-go to manage the risk. We tell everyone the rules and expectations so we don’t have to correct and address the daredevil style student.”

A natural fear of falling tends to weed out the majority of potential free soloists. Once a climber reaches about 15 feet, they do not proceed without ropes. It is a consensus in the climbing world that free soloing is the “fringe of the fringe,” a tiny community growing smaller in the current climbing boom of indoor gym climbers that has led to climbing’s debut in the 2020 Olympics. Even with the inherent risks to both the climber and those who may be unintended witnesses of a fatal fall, the question of regulating free solo climbing is widely seen as a moot point due to its rarefied nature.

“Even back to movies like Cliffhanger, potential land managers will bring up climbing without ropes, and it is an opportunity for us to make an educational point, that this style of climbing is really a televised phenomenon for the most part,” says Zachary Lesch-Huie, Southeast regional director for The Access Fund, a national climbing advocacy and conservation organization. Naturally, one would think Austin Howell’s recent death and the popularity of Free Solo could spook future work. Lesch-Huie has had to ease worries due to similar concerns in the past.

“We haven’t seen an increase in climbers out there trying to be Alex Honnold,” he says.

The Carolina Climbing Coalition (CCC) was established after a climber fell to his death in 1994. Climbers mistakenly worried that state parks would be closed to climbing as the result of a fatality at Crowder’s Mountain. State park officials and climbers met in Charlotte and determined that a park closure was not planned and that a coalition would best serve the interests of both climbers and park officials. In January 1995 almost 100 area climbers voted unanimously to create the coalition to help preserve climbing access in the Carolinas.

Mike Reardon

“We’re not the climbing police telling people how they should go climb.”

—Mike Reardon, Carolina Climbers Coalition

Mike Reardon was appointed Executive Director of the CCC last February. He described the charitable organization’s main mission is maintaining access to various areas by stewarding trails and working on bolt replacement. They also collaborate with landowners to open new areas to climbing.

“If it is something that affects access, then it is something we would take a stance on. We’re certainly not the climbing police who tell people how they should go climb.”

Mike Reardon shares the name with one of the most revered of free soloists. In 2007 the other Mike Reardon fell to his death free soloing a cliff in Ireland. After he fell into the cold water, a rogue wave took him away and he was never found.

He was 41 at his death, Austin Howell was 31. Howell spoke and wrote regularly about Reardon as somewhat of a ghost-mentor to him.

Howell had completed hundreds of free solo ascents across the country. One of his videos, documenting a free solo ascent completely naked save for a cowboy hat and boots, made it onto MTV’s Ridiculousness.

With the growing attention being paid to free soloists after Free Solo, he had begun to attract a larger following within the booming danger-sport landscape, alongside the skyscraper parkour and perilous selfies taken atop towers and on cliff edges. He had begun talks with a potential filmmaker to make a documentary about his exploits.

Howell got into climbing through a gym-wall in college. He excelled and began going to the gym regularly. During that time, he won a rope and safety equipment after participating in a raffle during a climbing exhibition. He told me how this led him to discover a new world of climbing outdoors. He quickly became a certified lead climber, and outdoor climbing took over his life.

It was acquiring safety gear that led him into outdoor climbing. It was putting aside that gear that took his life prematurely.