An hour and a half west of our nation’s capital is the rural community of Berryville, Va., population 4,304. A seemingly idyllic oasis among the northern Virginia sprawl, Berryville has all of the ingredients to be an outdoor recreation hub—the Appalachian Trail and Shenandoah River are both just minutes from downtown. So what’s missing? I went home to find out.

I always take the back roads when I’m home. My favorite is Lockes Mill. It begins at the end of Chilly Hollow, where pavement turns to gravel, and meanders along the bucolic banks of the Shenandoah River.

In high school, my friends and I would pile into one car and cruise its dusty length for no other reason than to watch the valley fly past our windows. It’s a beautiful drive any time of year. In the summer, tubers can be seen floating downstream in pods, all legs and cold beer, basking in the dappled sunlight streaming through the canopy. When the leaves have fallen and the summer crowds abate, the sycamore trees stand guard alone, their watchful white trunks bowing over the river.

The last time I drove Lockes Mill, it was an unusually mild winter day, the kind of crisp warmth that hinted spring was on its way. The sun was just beginning to dip beyond the horizon. As I passed by Watermelon Park, a bride-to-be looked up from her photo shoot. Out of reflex, I waved, and she returned the greeting with a smile that said I don’t know you, but I’m sure I do.

That’s how it is in my hometown of Berryville, Virginia: everyone knows everyone. It feels deeply familiar here, a timelessness that transcends my own family’s relatively short history living in Clarke County. Case in point: over 30% of the county is located within five National Register historic districts. From battlefields to plantation estates and pastureland fenced in by centuries-old limestone walls, the county is a living, breathing chapter of an American history textbook.

During the Civil War, the county was considered the “Bread Basket of the Confederacy.” The likes of George Washington and “the Gray Ghost” John Mosby made their way through here. After the war, wheat plantations turned to apple orchards and sprawling horse and cattle farms. I grew up on one of the latter, a 400-acre thoroughbred horse farm smack dab in the middle of the county.

It was here at the northern tip of the Shenandoah Valley that I first came to know and love the outdoors. And while the county’s farmland obviously provides fertile ground for fostering a love of nature, there’s plenty more in the way of natural resources, too—namely the Shenandoah River and the Appalachian Trail—that perfectly position Berryville to be a leading outdoor town.

Except, it’s not. Not yet, at least.

Back To The Future

Stacey Ellis was born and raised in Clarke County. We met for the first time back in February on her family’s property, Oak Hart Farm, situated just outside of Berryville. As we walked along the quiet fields in the shadow of the mountains, Ellis told me how she convinced her husband to return to her hometown for a slower pace of life. They now raise their two boys just three miles from Ellis’ childhood home.

“I love the fact that my kids have the same librarian that I did,” says Ellis. “I appreciate that I can take my kids down by the river and ride bikes on a gravel road. I feel kinda lucky in that sense.”

During the school year, Ellis is an Associate Professor and Program Lead of Health, Physical Education, and Recreation at Lord Fairfax Community College. In her hiking course, Ellis takes the class on day hikes and overnighters that are within the county or nearby, and says the majority of her students are unaware of the recreational amenities available in their own backyards.

Given that local resources for recreation have expanded in recent years, the disconnect is surprising. In 2013, Shenandoah University purchased and preserved 195 acres along the Shenandoah River. Previously a golf course, the Shenandoah River Campus at Cool Spring Battlefield now serves as an outdoor classroom and offers easily accessible walking and biking trails for the public.

Not long after the opening of Cool Spring, area mountain bikers secured access to the neighboring 1,400-acre Rolling Ridge Study Retreat. The 12-mile Perimeter Trail is now the only technical riding within county limits.

And in 2015, the Appalachian Trail Conservancy officially recognized Berryville as an Appalachian Trail Community. Situated just seven miles east of town, the white blaze runs for 22 miles through the county, including the 13-mile “Roller Coaster” section.

Despite these developments, not much has changed about Berryville since I lived there. Even Ellis sees little difference between the Berryville she knew as a child and the Berryville her kids know now, which is part of its charm. There’s a new high school (finally), a roundabout, a Greek place where the Tastee Freez used to be. But compared to its neighbor Loudoun County, which has consistently ranked as one of the fastest growing counties in the nation, Clarke County feels remarkably stuck in time.

Part of that is intentional says William Steinmetz, a local realtor and member of the town’s planning commission. Back in the 1980s, the county adopted Sliding Scale Zoning, which essentially concentrated growth in the town and limited development in the rural areas of the county. In effect, that zoning allowed Clarke County to maintain its open spaces, even while the rest of northern Virginia erupted in D.C. sprawl. Additionally, the county has long prioritized conservation. Not including the Appalachian Trail, over 27,000 acres (that’s one-quarter of the county) are currently protected in conservation easements.

“Geographically it can’t be ignored,” says Steinmetz. “It’s a really unique place that somebody started planning long before anybody was paying attention to that. It’s a reasonable distance from Washington, D.C., but we’re close to I-81, we’re on the river, there’s a mountain range that runs through the county, and there’s intentional open space but still a robust downtown that chooses to incorporate all of that into its identity.”

By all appearances, Berryville should be leading the way when it comes to bolstering an outdoor recreation economy. The town already has trail and river access, low-traffic country roads ideal for road cycling, a thriving arts scene headed by the Barns of Rose Hill, and killer bluegrass festivals like Watermelon Park Festival and Pasture Palooza. Located at the crossroads of routes 7 and 340, it’s easy to get to. There are three wineries and a number of quality restaurants. So what is keeping Berryville in the proverbial dark?

“This town walks into the future backwards,” says local and A.T. section hiker Lee Sheaffer. “It’s always looking behind them and a lot of that is good. You don’t want to change the quality of the community. But there are certain things that could be enhanced that are not going to change that quality and might actually help economically.”

Throughout his own Appalachian Trail experience, Sheaffer has passed through many towns that, when it comes to trail hospitality, are doing it right. Places like Waynesboro, Glasgow, and Damascus, Va., aren’t just conveniently located on or near the trail; they’re actively improving amenities for hikers to make the entire experience feel more welcoming. Even Front Royal, Va., just down the road from Berryville provides hiker boxes and shuttles to and from the trailhead.

“It would be advantageous to the town to really embrace the long-distance thru hikers,” says Sheaffer. “In Waynesboro, everything is really spread out. It’s almost a mile from where they put you up in a campsite to all of the businesses. In Berryville, if we can figure out somewhere to put these hikers up, everything you need is within 100 yards of where the center of town is: the post office, grocery store, laundromat, doctor. It would kinda be a no-brainer for people to come in and resupply.”

What Berryville is missing is affordable lodging. There are a few Airbnbs and bed and breakfasts, but not many. In 2013, a hotel feasibility study was completed, and support seems to be building behind the development of a small hotel. As far as camping, Rose Hill Park on East Main Street seems like the obvious place to let thru hikers crash, but opponents say allowing hikers to camp in town will increase vagrancy. That’s not been Sheaffer’s experience. Even if problems do arise, he says, the economic benefits would far outweigh the challenges.

“Talk to the Winks over at the Horsehoe Curve Restaurant [near the Appalachian Trail]. They know that dirty hikers come in with cash in hand. And here’s the thing—yes, they might smell and they might be dirty, but first off, they want a shower as bad as you want them to take one, and secondly, most hikers are newly graduated or newly retired. They have money and are willing to spend it for a certain amount of comfort.”

The times, are they a-changin’?

Even more so than the county’s Sliding Scale Zoning, what’s keeping Berryville seemingly unchanged is the pervading sentiment that life is good, simple, and sweet. The influx of people moving to town from Ashburn, Leesburg, and Purcellville come specifically for that easygoing pace. Change, however well intentioned, could threaten that.

“The crown jewel of Clarke County is its country roads and the road cycling experience,” says Frederick County Park and Stewardship Planner Jon Turkel, “but improving that comes with its own balance of challenges. You want to promote things to benefit from them but at the same time, you want to be careful that you don’t change the character in a way that would alter the interest or appeal of whatever that experience happens to be. It’s always a fine line between getting people to come and feeling like maybe there are too many people around.”

On any given summer day, the adverse effects of overuse can be seen in no better place than Lockes Mill, my beloved backroad. The Shenandoah River only has three access points in the county and one of those is Lockes Landing. Not only is the boat launch at Lockes Landing the smallest of the three, it’s also the most popular.

“I think people are recognizing the river is a great place to go but it turns negative when people are parking alongside the road,” says Clarke County Natural Resource Planner Alison Teetor. “It’s pretty overcrowded on the weekends and it is getting worse.”

The resulting tension, here and at other heavily used access points like the Appalachian Trail parking lot at Snickers Gap, pits private landowners against outdoor enthusiasts. That, in and of itself, can stall progress. The hope, says farmer and author Forrest Pritchard, is that the community can come together behind not just outdoor recreation but tourism in general to help diversify the county’s economy.

“If farmers have the wisdom to view this objectively, it might not necessarily be in their interest to bring in more folks but what it would benefit is our local tax dollars,” says Pritchard. “Clarke County is not some mining town out in the middle of remote Idaho. It’s ideally set up for tourism. I kinda consider Clarke like grandma’s dusty pearls sitting in her jewelry box. We know what we’ve got, we’ve appreciated it, but we’re still waiting to be fully discovered. When you find grandma’s vintage jewelry from the ‘20s, it suddenly comes back in style.”

Pritchard is part of a growing movement in Clarke County to meld the old with the new. Smithfield Farm has been in his family for seven generations, and in the past two decades, Pritchard has singlehandedly changed the farm from commodity-based agriculture to a sustainable grass-finished livestock operation that direct markets all of its food. During the season, Pritchard leads farm tours. He sees agritourism as a viable, alternative means of income for farms throughout the county.

I kinda consider Clarke like grandma’s dusty pearls sitting in her jewelry box. We know what we’ve got, we’ve appreciated it, but we’re still waiting to be fully discovered.

At the end of the day, Berryville needs more Pritchards to not only champion the potential but to then roll up their sleeves and make it happen. It’s easier said than done. Those who were born and raised and stayed in Clarke County might be like Mark Timberlake, who took over the family cattle farm some 20 years ago. Timberlake majored in outdoor recreation and was a raft guide and video boater on the New and Gauley Rivers throughout the ‘90s, but when he and his wife Michelle moved back to his father’s farm, all of that took a backseat to running a cattle operation.

“The first 10 years were really hard for me to get this thing up and going,” he says. “It took a lot of time working to get the farm where it needed to be, but raising our kids here in Clarke County on a 500-acre cattle farm, I can’t see any other place I’d want to be.”

Michelle agrees that as far as quality of life, Clarke County has it all. Both Mark and Michelle are mountain bikers now and enjoy the local trail at Rolling Ridge. She says compared to other small town recreation hubs like Davis, W.Va., Berryville ranks right up there with the rest as far as amenities. What it needs is to keep momentum rolling forward.

“I see so much potential of what could be done,” she says. “I think it will come, it’s just going to take the younger people not just demanding it but making it happen.”

The Making of a Mountain Town

Dig deeper into any small town success story and it’s clear the common denominator isn’t just the close proximity to rivers and mountains. It’s the selfless work of passionate people.

Take Franklin, N.C., for example. Back in 2010, when Outdoor 76 co-owners Cory McCall and Rob Gasbarro opened up their outdoor outfitter and taproom, Franklin’s Main Street was boarded up. Nobody thought they would make it through the year. Today, Franklin supports a thriving outdoors community comprised of tourists, locals, and those dirty Appalachian Trail thru hikers. There’s a budding restaurant scene and two breweries (in a town of 3,500). The town won our Top Towns contest two years in a row in 2015 and 2016. And at the heart of it all are Cory, Rob, Outdoor 76, and their hallmark race The Naturalist 25K and 50K.

About a half-hour’s drive north of Berryville, the college town of Shepherdstown, W.Va., has experienced similar success in the realm of outdoor tourism. Overlooking a bend of the Potomac River right at the Maryland – West Virginia border, the town of approximately 2,000 has always had a youthful vibe to it, thanks to the presence of Shepherd University. But with the exception of the cyclists touring the C&O Canal, outdoor recreation played very little role in the town’s identity.

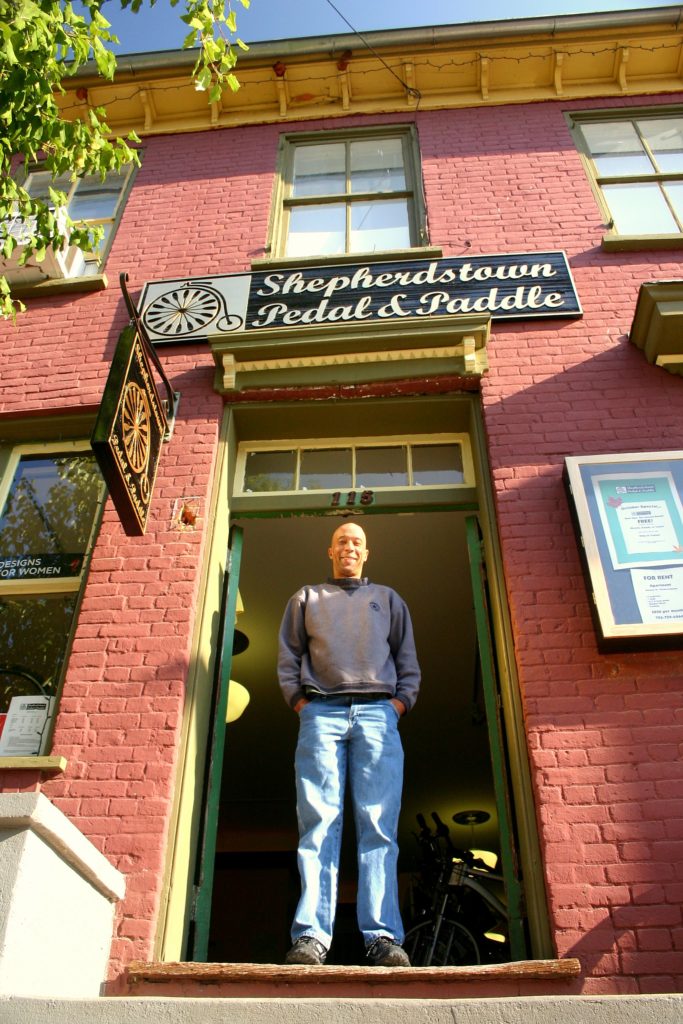

Then, between 2008 and 2009, two outdoor stores came to town that reshaped the local community: Shepherdstown Pedal & Paddle and Two Rivers Treads. With the support of these two shops and the creation of Freedom’s Run, an annual running race that funds numerous trail projects, Shepherdstown’s local outdoor community blossomed. For Eddie Sampson, owner of Shepherdstown Pedal & Paddle, the longevity of his business (which will celebrate its 11th anniversary this year) had everything to do with supporting locals first.

“For the most part, people living in a community don’t want others coming into their town because it gets crowded out, but when people start to realize that added amenities improve their quality of life every day and should be shared, it’s possible to get everyone on the same page,” says Sampson. “It can work for everyone. This is how small towns survive these days.”

For Two Rivers Treads owner and local doctor Mark Cucuzzella, serving the local community meant more than just providing a place for runners to buy shoes. It meant organizing group runs, providing free-of-charge seminars on nutrition and diabetes reversal, and even offering cooking classes to help West Virginia address some of its most serious health issues.

It also meant relocating his business out of Shepherdstown to the nearby town of Ranson, a suburb of Charles Town. Unlike Shepherdstown and Charles Town, Ranson lacked a lot of the resources its sister cities had. It was like “the poor steptown” in Jefferson County, says Cucuzzella. But over the past few years, the town has made many drastic improvements to its walkability by revitalizing sidewalks and adding streetlights. A multiuse trail connecting Charles Town and Ranson has already been approved and received funding.

Cucuzzella’s shop is one of the pillar retail businesses in Ranson’s downtown sector. When he goes out for a run, whether that’s in Ranson or in Shepherdstown, he’s rarely the only runner out there, and that, he says, is the first indication that a community is well on its way to becoming a mountain town.

“You’ve got to have playgrounds and walkable safe streets,” says Cucuzzella. “That’s your first step. You don’t need a national or state park, because even if you had that a mile away, if you gotta get in the car and drive there, it loses its impact because the kids that will need that experience most don’t have a car. Sure, it’s great to have a Harpers Ferry or an Antietam nearby, but an outdoor town can be one that just gets people outside.”

By Cucuzzella’s reasoning, maybe Berryville isn’t so far behind after all. Sure, there aren’t any cycling events like there used to be. There’s no brewery in town to make thirsty hikers linger longer. There’s no outfitter or bike shop or guiding service. But what Berryville lacks in these it makes up for with a remarkable pride in sense of place that is every bit as centered on the outdoors as all of the Boulders and Ashevilles of the world.

And perhaps, like Forrest Pritchard’s grandma’s set of forgotten pearls, Berryville is quietly shining in its own little corner, waiting to be discovered.