Over twenty years ago, the biggest manhunt in history took place in Western North Carolina for the Olympic Park and abortion clinic bomber.

On July 27, 1996, Eric Rudolph bombed the summer Olympics in Atlanta.

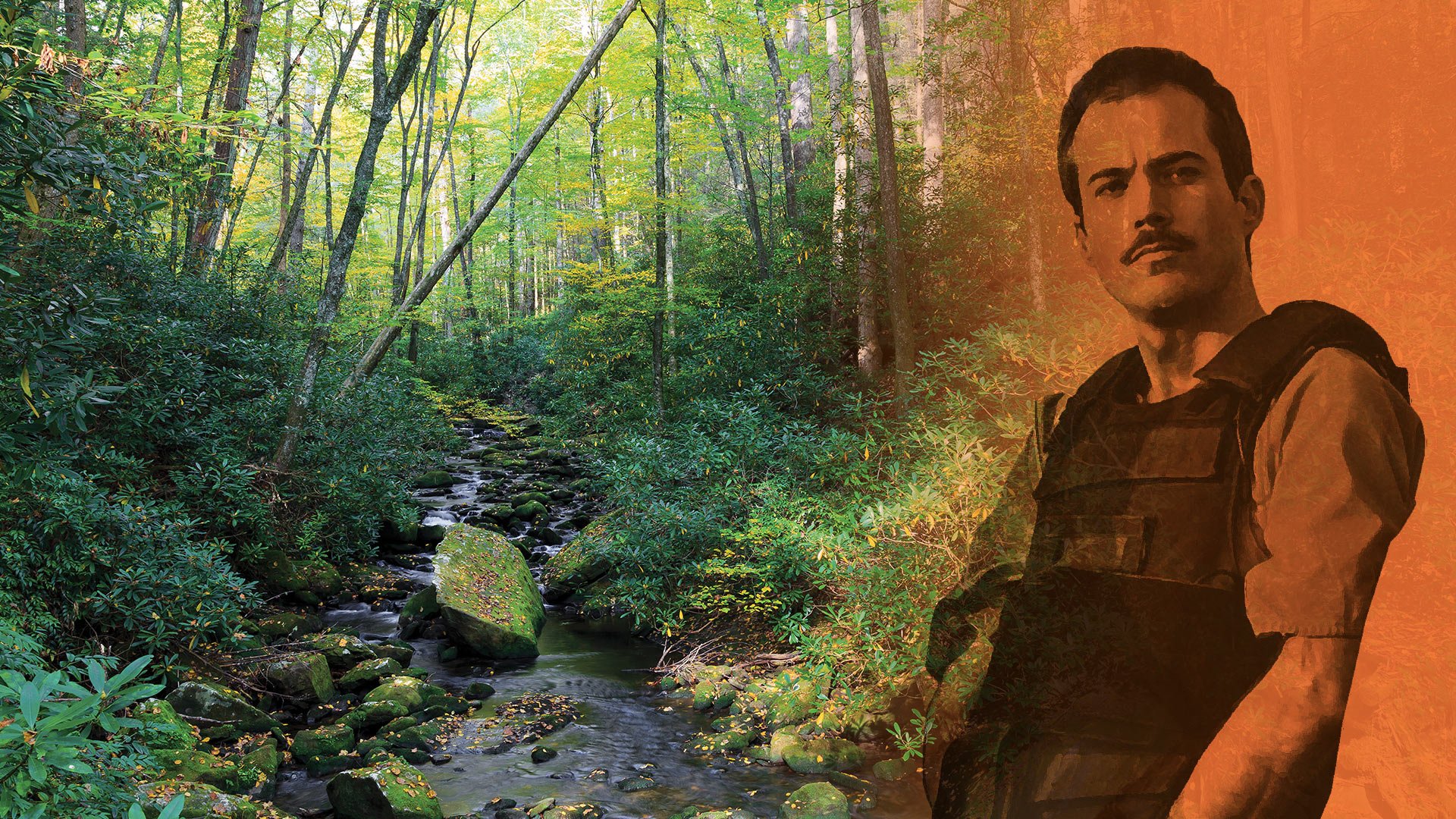

Over the next eighteen months a string of other bombings followed. Authorities finally closed in on Rudolph, but before they could nab him, he fled into North Carolina’s Nantahala National Forest. In the end, his manhunt cost millions and set off a culture clash that reverberated throughout the mountains and beyond.

Extremist Adolescence

By the time that Rudolph disappeared into the Nantahala National Forest on January 30, 1998, he knew the woods well. But he wasn’t a native North Carolina boy. Rudolph was born in Homestead, Florida, a flat savannah popping with palm trees, a landscape void of the forested ridgelines and plunging gorges he would one day call home.

According to Rolling Stone, Rudolph’s parents, Robert and Patricia, met in Manhattan. They were 1960s optimists and followers of Dorothy Day, a social activist who ran soup kitchens and led demonstrations against the Vietnam War.

The couple soon left New York and set their sights on the Sunshine State. Robert got a job with Trans World Airlines and they had six kids. Religion was a major part of their lives.

All in all, the family lived a pretty typical existence until 1981 when Robert died from cancer. After that, Patricia had the responsibility of raising all those kids on her own and it tested her faith. “I was mad at God,” she told Rolling Stone. “[God] didn’t heal Bob. Didn’t do anything.”

Some people point to this moment in time as Rudolph’s extremists beginnings, noting that the family may have blamed the federal powers-that-be for not green-lighting an experimental treatment that could have saved his life. Rudolph was 15, an impressionable age, and surely affected by his father’s death. Shortly after the family lost its patriarch, Patricia packed up the kids and moved to 6 acres in Nantahala, North Carolina.

The family lived off the grid, growing food and herbs and raising goats, ducks and chickens. They built a water system that did not require electricity. Rudolph spent a lot of time outside and a lot of time with his neighbor, Thomas Wayne Branham, a man of radical politics who considered himself to be free of the confines of state and local laws. When Rudolph was 17, the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms raided Branham’s home. According to Rolling Stone, they found a submachine gun, a short-barreled shotgun, two M-16 conversion kits, four sticks of dynamite, electric blasting caps and manuals about bombs and other unconventional warfare devices. Branham was outraged at what he saw as a major invasion of privacy. The Rudolphs were pissed about it too.

By this point Eric had dropped out of high school and Patricia was home schooling him. She’s quoted as saying, “I taught [my kids] to be creative thinkers. [To] not accept the status quo, always question.” Even so, later that year, at the encouragement of Branham, she packed Eric up and moved him and his little brother to Schell City, Mo., where Dan Gayman, a leader in the Church of Israel and follower of the anti-Semitic, racist and homophobic Christian Identity Movement, maintained a compound. They lasted four months before retreating back home to the mountains of North Carolina. It’s unclear what Eric Rudolph gleaned from the experience, but for her part, Patricia described that time period by saying, “everybody makes mistakes.”

After that, Eric earned his GED and attended a few semesters of college at Western Carolina University. When he dropped out of college he joined the Army and served with the 101st Airborne Division. At Fort Campbell in Kentucky, he learned how to handle explosives. But his time in the military was cut short when he was discharged for using marijuana.

Once again, Rudolph came back to the Nantahala Mountains. He lived alone and supported himself doing carpentry jobs in the region. He didn’t use credit cards or bank accounts because he believed that authorities would track him through his card number. In 1996 he toyed with the idea of leaving North Carolina, lamenting the fact that the mountains were becoming too populated. According to Rolling Stone, he also believed that the bigwigs in Washington D.C. were plotting to provoke a national catastrophe and use it as a reason to declare martial law. Their end game, thought Rudolph, was to throw all Christians, including himself, into concentration camps.

He left Nantahala but didn’t go far, renting a trailer 30 miles down the road in Murphy.

A few months later, bombs began exploding across the south.

A Bomb Goes Off

In July 1996, athletes from around the world converged in Atlanta, Georgia to compete in the Olympic summer games. A few years earlier, the International Olympic Committee had voted to separate the winter and summer games, holding them in alternating years, and this was the first time the summer games were to be held on their own. At the opening ceremony, Celine Dion crooned the official Olympic theme song called “The Power of the Dream,” and Gladys Knight belted “Georgia on my Mind.” An entertainment showcase called “Welcome to the World,” featured bouncing cheerleaders, 2-step marching bands, and Chevy pickup trucks meant to demonstrate to the world the weekend football culture of the South. It’s doubtful that Rudolph, who was likely still 120 miles away in Murphy, saw any of this.

According to The New York Times, about midway through the summer games, on July 27, 1996, someone called 911 in Atlanta. “There is a bomb in Centennial Park,” said the caller. “You have 30 minutes.” A security guard discovered the explosive hidden inside an abandoned backpack and began evacuating the area. Still, the bomb exploded, spewing nails and shrapnel into the crowd. A 44-year-old woman named Alice Hawthorne was killed and over 100 others were injured. Authorities suspected the security guard—no one yet knew the name Eric Robert Rudolph.

Six months later, on January 16, 1997, bombs exploded in Atlanta once again. This time, two bombs detonated outside of the Northside Family Planning Services clinic, a health care provider that performed abortions. No one was killed in the bombing, but 4 people were injured.

On February 21, 1997, another bomb went off. This time the target was the Otherside Lounge, a gay nightclub in Atlanta. The blast injured 4 people, and a second bomb exploded while being handled by police robots.

Rudolph’s final bomb detonated a year and a half after the Atlanta Olympics outside of the New Woman All Women Health Care Center in Birmingham, Alabama—a clinic that also provided abortions. This time, an off-duty police officer was killed in the blast and a nurse severely injured. Unlike in bombings past, this time a vigilant bystander saw a man walking away from the chaos and tracked him back to his truck, taking note of his North Carolina license plate.

The next day, news organizations began receiving anonymous letters crediting the Virginia-based Christian anti-abortion terrorist group Army of God with the bombings. The New York Times reported that the letters warned that “anyone in or around facilities that murder children may become victims of retribution.” The letters also said, “death to the New World Order.”

But by the time the letters began arriving at media outlets, federal agents were closing in on Rudolph. Unaware that he had been identified, Rudolph spent his day renting a movie and grabbing a meal at Burger King.

Bill Hughes was the Mayor of Murphy from 1997-2017 and remembers the time well. The frustration in his voice mounts as he recounts the events around the day that Rudolph went missing. “Our sheriff at the time was Jack Thompson,” explains Hughes. “When the FBI called him he said, ‘I know where [Rudolph] lives and I’ve got a plan. We’re going to surround the trailer so he can’t get out.’” But the FBI had other plans. “They said, ‘Absolutely not. You wait until we get there,’” remembers Hughes. “Well, it took them three hours to get to Atlanta. By the time they got with the sheriff and got out to Rudolph’s place, he was gone.”

When federal and local authorities arrived at Rudolph’s trailer, they found the door swinging open and the lights on. They surmised that he had managed to grab a month’s worth of food—raisins, green beans, and trail mix, before bolting. His truck was found abandoned in the woods about a week later by two raccoon hunters.

Rudolph was definitely gone. And he remained gone for a very long time.

The Manhunt

Under a robin’s egg sky, I drive to the town of Murphy, North Carolina, hoping to dig through a file of newspaper clippings preserved at the Murphy Public Library. My route from Asheville leads me through the Nantahala National Forest, where Rudolph lived before moving to Murphy. Nantahala is a Cherokee word that means “land of the noonday sun,” but the hemlock, oak, pine, and rhododendron are so thick beyond my windshield that it’s a wonder the light in these woods can reach the ground at all.

I drive past Andrews High School, where Rudolph sometimes sat in a tidy mountaintop camp only 200 yards away, a spot that provided him a birds-eye-view of town. A few minutes later, I pass the Western Carolina Regional Airport, where, as Bill Hughes tells it, a Learjet carrying a man with a briefcase would land just about every week while Rudolph was on the run.

Twenty minutes later, I arrive in Murphy, the town where Rudolph was living when he disappeared, and park my car behind the modest public library. Inside, the librarian hands me a fat manila folder and sits down to chat. She didn’t live in Murphy when Rudolph was on the lam, but she did come to town for vacation one year and remembers when the Armory was used as FBI headquarters and helicopters roamed the sky searching for Rudolph. “We still have his library card,” she tells me. He’d come in sometimes to borrow books before he disappeared into the forest.

They have a copy of the book Rudolph wrote from behind bars, too, called Between the Lines of Drift: Memoirs of a Militant. It was self-published and distributed online by Army of God, the organization that first sent those letters claiming responsibility for the bombings. But the Murphy Public Library bought their copy directly from Rudolph’s own mother. The librarian tells me that Rudolph describes in his memoir how he would steal books from the Book Mobile they used to have parked out back, right there in the middle of town.

What I’m looking for I don’t quite know. The folder contains articles clipped from the Asheville Citizen-Times and the Atlanta Journal-Constitution and printed from The New York Times. They document the days after Rudolph’s capture, when the media descended upon the tiny hamlet and Murphy, North Carolina became the center of the world.

But before that day, there were five years that preceded it. Five years where the FBI scoured the Nantahala National Forest with bloodhounds, electronic motion detectors, and heat-sensing helicopters. They set up listing posts with cameras and hired local scouts to tromp through the woods with gridded maps. They named Eric Robert Rudolph to their Most Wanted List and put a $1,000,000 price tag on his head. That’s when the bounty hunters came crashing into town, determined to make a fortune off of finding Rudolph.

From the very beginning, there seemed to be a rift between the federal authorities and the locals who knew the area well. In 1998, Chris West, who at the time was the assistant police chief of Andrews, told the Citizen-Times, “The FBI is keeping it pretty hush. We could have given them help with the terrain, shown them spots they need to check out—caves, caverns, old mountain homes. But they haven’t asked us.”

Doug Franklin was living in Nantahala during the manhunt years. He didn’t know Rudolph, but they shared the same occupation. At the time, Franklin was doing carpentry work in Andrews, and each day as he commuted to and from work, he’d drive by a spot on the side of the road where the FBI had a small command center. “It seemed to me like a farce more than anything else,” Franklin said. “They had coffee pots set up on the side of the road, and you’d see them sitting or standing there and their uniforms were perfectly clean. No dirt on it, just a clean uniform. So that told me that they hadn’t been very far out in the woods looking for him.”

It’s probably not a far stretch to assume that many people in town viewed the FBI with a skeptical eye. They were seen as city slickers who swooped into the mountains without any real knowledge of the terrain they were working with. “I felt like the government was just using it as a training exercise more than anything else,” says Franklin. “Maybe using it to get more publicity and get more funding.”

At the same time, the FBI did not try to hide the fact that they believed that many of the locals sympathized with Rudolph and may have even been helping him evade capture.

Kelly Bryant lives in a little community called Marble that sits halfway between Andrews and Murphy. Back in the 90s, she worked at a gas station in the area, and Rudolph would come in from time to time. After his escape, she assumed people were helping him. “I assumed that’s the only way he could stay alive in the woods that long. But that’s just me,” she says. When I asked her if she ever worried that Rudolph might come out of the woods and hurt someone, she replies, “Honestly that never crossed my mind. I figured he would stay in hiding for as long as he could.”

I can find no current or historical expression of fear from anyone discussing Eric Rudolph. On my drive into town, I passed a smattering of pro-life billboards, and it’s no secret the way politics lean in most small, Southern towns. I wonder if the lack of fear came from knowing that a small town with conservative values would never be Rudolph’s target. He was just their extremist in the woods.

Bill Hughes is adamant that Rudolph never received any outside help. “I said from the beginning Eric Robert Rudolph was a lone wolf. He was the kind of person who felt like if more than one person knows something, it’s no longer a secret.”

Until the day of his capture, the last confirmed sighting of Eric Rudolph was on July 7, 1998, when he showed up at health food store owner George Nordmann’s house in Andrews and asked for help. Nordmann says he declined to help, but he didn’t report the encounter until two days later when Rudolph stole his truck and 75 pounds of food. Police recovered Nordmann’s vehicle abandoned at a trailhead, but by then, Rudolph had disappeared into the woods again.

Hughes said that occasionally they would hear of a cabin or summer home being broken into, but nothing was ever destroyed. “Things would be taken like soap, toothpaste, underwear, socks, a heavy jacket—something like that,” says Hughes. “They suspected that was Rudolph.”

Meanwhile, authorities continued to comb the mountains around Murphy. An FBI Scout who shared his story with me on the condition of anonymity said that he was hired because of his familiarity with the area. “The FBI made it known that they were looking for people with local knowledge of the terrain,” he said. They hunted all around the Nantahala National Forest within a 45-minute drive of Wesser, North Carolina. “Much of the terrain was rugged and remote,” he said, “but some was near houses. We spent a fair bit of time observing within four miles of his last known habitation.”

Each week the scout and his team, who were assigned aliases and called by those names, would receive a map with grids to search. At the end of the week, they’d meet with FBI agents in their black Suburbans at a rendezvous point and report anything questionable they had seen. Then they were paid in cash. When I asked the scout if he received any special training to hunt for Rudolph, he said that it was easy to prepare. “We all knew how to read maps, we knew the terrain, we were all outdoorsmen and women, and we didn’t mind being uncomfortable in any weather. It was often cold and there was a lot of snow. Most of us did not have weapons—maybe a knife. It was fun.”

But all of that manpower led to nothing. By 2000, the search had been scaled back. By the spring of 2002 there were only a dozen agents on the case. A year later, there were only two agents in Asheville coordinating a team of paid scouts. There was speculation that Rudolph had died somewhere out there in the dense, wet woods.

The FBI spent five years and a reported $24 million searching for Rudolph and turned up empty-handed. Then on May 31, 2003, a 21-year-old rookie with the Murphy Police Department named Jeffrey Postell caught a man dumpster diving behind the Save-a-Lot in the middle of the night. When asked his name, the man said he was Jerry Wilson of Ohio. “I didn’t have a clue who he was,” Postell later told MSNBC. Without even knowing it, Postell had just apprehended one of the most wanted men in America.

Brought to Justice

Postell was out on his overnight rounds checking up on local businesses when he spied a man digging through a dumpster behind a grocery store. The man had a flashlight that Postell initially mistook for a weapon. When he pulled his gun, the man peacefully surrendered.

Confronted back at the station, Rudolph quickly owned up to his identity. “You know it’s interesting,” Hughes tells me, “when Postell had him in the back of the car he mumbled something like, “I’m glad it’s over. I’m tired of running.” After five years and one of the nation’s most costly manhunts, the whole thing ended in an anticlimactic whimper.

When he was arrested, Rudolph was wearing a blue work shirt and pants, running shoes, and a camouflage jacket. His hair was cropped short and he had a mustache. His fingernails were clean. Though he’d dropped 30 or 40 pounds, the fact that he wasn’t a wild-haired, rag-wearing vagrant added to the speculation that he’d had help along the way.

Once again, the media descended upon Murphy. “Suddenly there were snipers on top of every building,” remembers Hughes. “The courthouse and jail were cordoned off. There were TV trucks everywhere. After his arrest, I counted 26 satellite trucks in Murphy. The joke was the reporters had to wear arm bands to keep from interviewing each other.”

Attorney General John Ashcroft issued a statement saying, “American law enforcement’s unyielding efforts to capture Eric Robert Rudolph have been rewarded. Working with law enforcement nationwide, the FBI always gets their man.” It was a boastful pat on the back that must have had many in Murphy rolling their eyes.

After his arrest, details began to emerge about Rudolph’s years on the run. “He had two locations,” says Hughes. “He had one here on the mountain close to Murphy where he could keep watch on FBI movements every day. And he had a camp near Fires Creek.” It was here in the Fires Creek area that authorities found a campsite hidden deep in the woods. It was scattered with deer hides, wild turkey remains, a high-powered rifle, and food containers that Rudolph may have hung from the trees to keep the animals away. Authorities also found plywood, roofing paper, books, and cooking supplies. At the time, the Sheriff of Clay County, Tony Woody, was quoted as saying, “you could walk within 10 feet of it and never see it.”

From prison, Rudolph began writing letters to his mother describing how he managed to survive in the woods for so long. He told stories of raiding dumpsters at McDonalds and the grocery store. Sometimes he’d dig through the dumpster at the movie theater for popcorn. He’d pluck food from gardens and pilfer grain from silos, transporting it all in a truck he stole from a used car lot. Back at camp, he would boil the grains and then pound them into pancakes and fry them.

He told his jailers that he lived off of nuts, berries, wild turkey, bear and salamanders that he swallowed whole like sushi. In that version of the story, Rudolph paints himself as a survivalist. But from the stories he tells his mother, it sounds as though Rudolph spent much of his time lurking in the shadows on the edge of society, living off the excess of the community.

Today, Eric Rudolph spends 22.5 hours alone in an 80-foot concrete cell. He’ll spend the rest of his life in prison without the chance of parole after pleading guilty to all of the charges he was accused of in exchange for avoiding the death penalty. As a part of the deal, he also agreed to show the FBI where he had hidden 250 pounds of dynamite in the forest. He was sent to ADX Florence Supermax federal prison in Colorado, and it is there where he will spend the rest of his days. Through it all, Rudolph denied having any help surviving in the woods. The FBI eventually accepted the theory that he acted alone.

Culture Clash

Bill Hughes was angry then, and it still gets his guff now, that some of the media portrayed the town of Murphy as a backwoods dot on the map filled with townies that ideologically supported Eric Rudolph. “They painted a picture of us being illiterate hillbillies down here—just a little two-bit, sawmill, every other building a church sort of thing,” says Hughes. “They said we were able to identify with Rudolph and were sympathetic to him, which was totally false.”

Yet newspapers of the time reported that residents printed bumper stickers that said “Run, Rudolph, Run,” and wore t-shirts that read “1998 Hide and Seek Champion Eric Rudolph.” After his arrest, the local coffee shop served “Captured Cappuccinos” and a sign posted outside of town read “Pray for Eric Rudolph.” The Christian Science Monitor ran a story claiming that Rudolph autographed his “Wanted” posters for sheriff’s deputies after his arrest. It’s easy to see how the whole thing could have felt like a three-ring circus for residents that were used to living in sleepy little Murphy, that their actions were good-natured and simply meant to poke fun at all of the hoopla. But Rudolph wasn’t a funny guy, and many construed those actions as a distasteful expression of support for the bomber.

Dig through the papers of the time and you’ll see that dynamic play out on a wider stage. Letters to the editors of papers in Asheville and Atlanta illustrate how some viewed Rudolph as a folk hero. One letter to the Citizen-Times dated June 14, 2003 encouraged the FBI and the courts to have compassion towards the “dear souls” who may have been helping Rudolph hide. The author of the letter wondered if investigators would find that people aiding Rudolph were just “merely a product of their Appalachian upbringin’ where folk learn to take care of one another,” adding that perhaps helping those in need is “the very nature of the natives of Western North Carolina.” Another letter to the Citizen-Times states flatly, “If I had lived in Murphy, I would have helped him.”

But an opinion piece in the Atlanta Journal-Constitution that ran the same week reminded readers that “eluding capture in the wilds of North Carolina doesn’t make Rudolph a folk hero.” And when an author from North Carolina wrote a sentimental and sympathetic op-ed in The New York Times called “Why We Fed the Bomber,” responses published a week later pushed back. “Let me be clear,” came one letter from Raleigh, “overwhelmingly, the people of North Carolina believe Eric Rudolph to be a bigoted and cowardly killer.”

The years have passed in Murphy and the name Eric Robert Rudolph is no longer on the tip of anyone’s tongue. “He’s faded into memory,” says Kelly Bryant. “Unless there is an anniversary or someone makes a point of bringing it up, he isn’t talked about anymore.”

“I haven’t heard anything about him in years,” says Doug Franklin.

“I assume he’s still in prison, but I don’t even know.”

A film by Clint Eastwood tells the other part of the Olympic Park bombing story. “Richard Jewell” opened in the US on December 13, 2019.

Richard Jewell is a 2019 American biographical drama film directed and produced by Clint Eastwood and written by Billy Ray, based on the 1997 article “American Nightmare: The Ballad of Richard Jewell” by Marie Brenner, published in Vanity Fair. The film depicts the Centennial Olympic Park bombing during the 1996 Summer Olympics in Atlanta, Georgia and its aftermath, where security guard Richard Jewell found a bomb and alerted authorities to evacuate, only to later be wrongly accused of having placed it himself. It stars Paul Walter Hauser as Jewell, alongside Sam Rockwell, Kathy Bates, Jon Hamm, and Olivia Wilde.

The story of Richard Jewell’s involvement in the hunt for Eric Rudolph was also told by a 2017 TV series called ‘Manhunt’

Manhunt is an American drama anthology television series created by Andrew Sodroski, Jim Clemente, and Tony Gittelson, initially commissioned as a television miniseries starring Sam Worthington and Paul Bettany. It depicted a fictionalized account of the FBI’s hunt for the Unabomber and premiered on Discovery Channel on August 1, 2017. On July 17, 2018, Charter Communications was in advanced negotiations with the series’ producers to pick up the series for two additional seasons to be aired on their Spectrum cable service. The show’s second season followed the hunt for Eric Rudolph, who was the perpetrator of the Centennial Olympic Park bombing after suspicion initially fell on security guard Richard Jewell. On January 18, 2020, it was announced that the second season Manhunt: Deadly Games would premiere on February 3, 2020.