Wetting a line.

Somewhere along the skinny Rose River in Shenandoah National Park, Travis McDowell lost count of the number of fish he’d caught.

“Forty? 50? I’m not one for keeping track anyway, but I know I saw action in 80 percent of the pools I fished,” McDowell says, describing how he spent the majority of his day scrambling over boulders and sneaking from one tiny pool to the next, moving up the headwaters of a stream.

Most anglers stick to the larger trail-side portion of the Rose, a stretch listed in plenty of Mid-Atlantic fly fishing guide books, but McDowell wanted something more remote. He consulted his topo, followed the blue line as it curled away from the trail, and set out for an adventure. His only company the entire day were the fish he caught. And he landed them using the most rudimentary fly fishing set-up imaginable.

“Just a rod, line, and fly,” McDowell says, naming the “trinity” of tenkara, an ancient style of fly fishing practiced for centuries in the mountains of Japan. It’s a streamlined version of the sport that’s similar to Western fly fishing, but with one significant difference: with tenkara, there’s no reel. Instead, a fixed line is attached to the tip of the rod. According to tenkara enthusiasts, the lack of reel simplifies the experience, boiling fly fishing down to the bare necessities.

“It’s like single speed mountain biking,” says McDowell, an unofficial “tenkara ambassador” and former mountain bike racer who has all but abandoned his Western style fly rods for their streamlined Asian cousins. “The singlespeed is light and gear-less, so you don’t have to worry about the drivetrain. You can focus on the experience. That’s tenkara.”

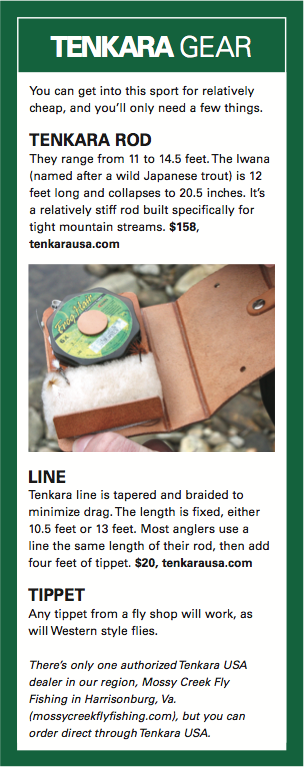

Tenkara rods are typically longer than their Western counterparts, but because there are no eyelets, you can telescope each rod down to around 20 inches. The line is also lighter and braided to reduce drag on the water. Add some tippet and a fly on the end of the fixed line, and that’s your whole system. It’s an almost complete lack of clutter that puts as little as possible between you and the fish.

Tenkara rods are typically longer than their Western counterparts, but because there are no eyelets, you can telescope each rod down to around 20 inches. The line is also lighter and braided to reduce drag on the water. Add some tippet and a fly on the end of the fixed line, and that’s your whole system. It’s an almost complete lack of clutter that puts as little as possible between you and the fish.

“For me, it’s the simplicity,” says Daniel Galhardo, founder of Tenkara USA, the only manufacturer of tenkara style rods that distributes in the U.S. “The idea that I can fish anywhere and not have to fumble with the reel, and passing the line through the eyelets…all these little things that end up taking up an enormous amount of time. There’s none of that frustration because there are so few pieces to deal with.”

While the minimalist art form has been around for centuries in Japan, originating with poor, professional fishermen who had to catch fish with only the most rudimentary equipment at hand, it’s just now beginning to gain popularity in the United States. Tenkara officially made its way to the U.S. in 2009, when Galhardo founded Tenkara USA. The 28-year-old avid rock climber and backpacker spent months studying with the Japanese masters of Tenkara and is hell-bent on spreading the tenkara gospel to the Western world, mostly through an online community and grassroots devotees like McDowell. Tenkara has yet to hit the mainstream, but just three years after its introduction there are almost as many tenkara anglers in the U.S. as there are in Japan. The sport is growing steadily in mountain communities where backpackers, mountain bikers, rock climbers, and paddlers are drawn to tenkara’s zen-like simplicity.

“Younger athletes in particular are picking up tenkara, even though Western fly fishing didn’t resonate with them,” Galhardo says. “Simple things have their appeal, and a certain kind of person is attracted to the philosophy of tenkara; the notion of relying on technique instead of gear. We’re going against the grain in the U.S. Look at a fly fishing magazine and you’ll see all this complicated stuff. Twenty different fly lines for different sizes of trout, vests, floatants, split shot…why do you need all these things? All that gear is intended to make fishing easier, but all of a sudden you’re cluttered and the gear actually makes the sport more difficult.”

Don’t let all the philosophical talk fool you. Tenkara is as practical as it is peaceful. Even though tenkara rods are two to four feet longer than Western rods built for cold water, tenkara anglers insist they’re actually better suited for the tight, brush-choked streams found on the sides of mountains. While the rod is longer, the top third is remarkably pliable and the line and fly are much lighter than a Western set up. The result is a tighter, less dramatic cast.

“I fish small brook trout streams and I’ve yet to have a problem with the rod being too long,” says Tom Sadler, a Virginia-based fishing guide and an early adoptee of tenkara. “Since you don’t have to load the road as dramatically, you can keep the rod in front of you and out of the brush behind you.”

The longer rod also means you have an extended reach across the stream without the need for extra line. When all is said and done, a tenkara cast looks a little different than a conventional fly cast. The physics are the same, but there’s less motion, and much of the cast is performed with a flick of the wrist. Typically, you’ll end your cast with your elbow in front of you, your arm held high to keep everything but the fly and tippet out of the water. And your left hand, or non-casting hand, is completely still since there’s no reel or extra line to manage.

“With small mountain streams, you don’t need all that extra line you find in a Western fly fishing system,” says McDowell. “You’re not performing big River Runs Through It casts. There’s no room for that, so the reel basically becomes a fancy line holder.”

The minimalist nature of the sport also means anglers can go deeper into the backcountry with less gear to carry and fret over. Moving from stream to stream is a cinch because the rod telescopes to pocket size, and minimalist anglers can get away with carrying nothing more than the rod, line, and a small can of flies.

“When I saw tenkara for the first time in Japan, I knew immediately is was perfect for backpacking,” Galhardo says. He tells a story about exploring a remote canyon in Japan, wearing a wetsuit and rappelling down a series of waterfalls to fish for a rare native trout species inside shallow pools completely enclosed by mossy rock walls. The scene is similar to the streams you’ll find dropping into Lake Jocassee on the border of North Carolina and South Carolina, or the tiny creeks that fall from the ridges of Shenandoah National Park in Virginia. Most anglers never set foot in these tough-to-access headwaters, but tenkara fishermen seem to pride themselves on fishing gnarly, technical water.

“Hike one mile from the access point and you’ll lose 90 percent of fishermen,” McDowell says. “Hike two miles and you’ll lose the other 10 percent.”

Because of the supreme packability and minimalism of a tenkara system, McDowell sees big potential in the outdoor community. “Tenkara is the perfect complimentary activity to the things people are already doing. It packs down to a few inches, weighs next to nothing. You can fit it in the hull of a kayak. Slip it into your daypack. Mountain bikers could even fit a Tenkara rod in a hydration pack. Fly fishing tends to be gadget heavy. A vest, a chest pack, shoulder bag, waders, more flies than I can count. But now I just throw the rod, line, and a tiny fly box in my day pack and hit the woods.”

The streamlined system also makes tenkara more approachable for beginners and, ultimately, easier to learn. In Western fly fishing, managing the line on the water with your left hand and reel is a big part of success and often a tough obstacle for beginners to overcome, but in tenkara a beginner only has to worry about his cast. Even the cast is easier to pick up because of the long rod and short line.

“Tenkara doesn’t put a premium on casting techniques,” says Tom Sadler, the only recognized guide who’s teaching tenkara in the Southeast. “It’s easy to get the fly line in the water, raise the line out of the water and follow the fly with the tip. You learn quickly and catch fish quickly. Tenkara is getting people into the sport of fly fishing, and they’re sticking with it.”

Sadler, who teaches out of Mossy Creek Fly Shop in Harrisonburg, Va., estimates the store is selling more tenkara rods than conventional rods at this point. Tenkara’s potential to attract new users prompted Patagonia founder Yvon Chouinard to proclaim, “Tenkara will be the salvation of fly fishing.”

It’s winning over long-time Western-style anglers as well. Sadler himself is convinced he’s catching more fish since switching to tenkara, a common observation shared by long-time anglers turned tenkara devotees. Sadler explains his greater success not with mysticism, but with math.

“With tenkara, you only have a few inches of tippet in the water leading to the fly. With Western fly fishing, you have six feet of line leading to the fly. The lack of line in the water reduces drag and allows the fly to behave more naturally,” Sadler says. “It leads to a better presentation for the fish.”

And a better presentation of the fly means more fish rising to take that fly. Or, as McDowell puts it: “The more line you have in the water, the more the fish knows you’re full of shit.”

Combine the simplicity of tenkara with its effectiveness, and you get a small-but-rabid population of anglers who often come across as zealots. Passion exudes within online tenkara forums and stream-side conversations. One fisherman even got the Tenkara USA logo tattooed to his arm. It’s an enthusiasm that’s similar within the fixed gear bicyclist crowd.

“I fished with one guy in California who says tenkara changed his life,” Galhardo says. “He’d always been a backpacker, but I think tenkara gave him a purpose in the backcountry. It gave him a pursuit and changed his outlook on the outdoors.”

Want to get into Tenkara? Enter our Match the Hatch Giveaway for your chance to win a new Tenkara Rod from Mossy Creek Outfitters!

Tenkara Streams

Tenkara is made for tight mountain streams that support wild brook. The sky’s the limit in Southern Appalachia. Here are a few favorites:

Piney River

Shenandoah National Park, Va.

The Piney Branch Trail crosses this wild trout stream a couple of times, allowing for relatively easy access. Hike to the second trail junction and begin bushwhacking and fishing your way upstream.

Hazel Creek headwaters

Great Smoky Mountains National Park, N.C.

Head for an elevation above 3,000 feet to avoid the non-native rainbow and brown species that have been introduced to the park. Hazel Creek is the perfect example. Where this famous stream hits Lake Fontana, it’s filled with browns and rainbows, but if you head to the stream’s narrower, steeper headwaters below Clingman’s Dome, you’ll find tiny, shifty brookies, and far fewer anglers.

North Harper Creek

Pisgah National Forest, N.C.

North Harper Creek begins near the Blue Ridge Parkway in the Wilson Creek Area of Pisgah National Forest and runs fast and cold before it joins the Wild and Scenic Wilson Creek. The stream is full of gin-clear pools that house mostly rainbow and brown trout, but the occasional native brookie can be found. Access the creek via the North Harper Creek Trail, a rugged and secluded path that crosses the river half a dozen times, so both access and solitude are plentiful.

Conasauga River

Chattahoochee National Forest, Ga.

The headwaters of the Conasauga River are so tight, a new angler might think the creek wouldn’t hold trout. In fact, this is one of the most beloved native brook streams in North Georgia. Almost 15 miles of the crystal clear Conasauga run through the Cohutta Wilderness Area of the Chattahoochee National Forest. Most of that stretch is accessible via the Conasauga River Trail, which crosses the creek almost 40 times in 13 miles. Consider an overnight trip, as the river is remote and backpacking sites abound.

Noontootla Creek

Blue Ridge Wildlife Management Area, Ga.

Noontootla starts as as a spring on Springer Mountain and drops steeply through the Blue Ridge Wildlife Management Area on its way to the Toccoa River. Larger rainbows and browns can be found down low, but if you stick to the high elevations where three tributaries (Chester Creek, Stover Creek, Long Creek) feed Noontootla, you’ll find native brook. Access the creek from Forest Road 58 inside the Blue Ridge WMA and head upstream.

For a recent article dispensing fly fishing myths, and a list of local places to go, visit here!