When you see accomplished athletes, do you ever wonder how they got there? What their upbringing was like? Whether their parents led by example or lived vicariously through their children? Have you ever pondered whether a tendency toward adventure is acquired through nature or nurture?

As I sat below Sweet’s Falls on the Upper Gauley, watching a kid no older than ten years old style the class IV rapid in his toy-sized playboat, I wondered those exact things. At first, I thought his parents must be either clueless or negligent or both. But when I saw the boy fist-bump a man I assumed to be his father in the eddy below, I had a change of heart.

How cool, I thought to myself. What better way to bond with your son than by leading him down one of the best stretches of whitewater in the world?

Seeing the father-son duo got me thinking about my own upbringing and my introduction to the world of adventure. Though I certainly know a number of professional athletes who don’t take after anyone in their family, the majority of outdoor enthusiasts I know can trace their love of adventure to childhood memories of camping trips.

The following four families are rooted in adventure. They spend more time in the woods than at the dinner table. Their weekends are spent on the river and at the crag. From rippers-in-training to sponsored athletes, see what these four families have to say about passing the torch, the lessons they’ve learned, and what a little playtime can do for a family.

The Jackson Family, Boone, N.C.

For father and teacher Kristian Jackson, riding bikes isn’t just a hobby—it’s been a lifelong love affair and a defining part of his character.

“From a very early age I was playing in the woods,” Kristian remembers. “I grew up riding and working on bikes for as long as I can remember.”

That happened, in part, because Kristian’s father himself was in the bike industry. Inevitably, biking went hand in hand with the Jackson family outings. A vacation was never complete until Kristian and his father were in the saddle.

“Riding bikes was kind of ingrained into our camping trips,” he says. “It was a normal thing for us.”

Normal, despite the fact that Kristian was a young child during the late ‘70s and early ‘80s, a time when mountain biking was practically non-existent and outdoor recreation in general was just starting to boom. Still, Kristian maintained that early love of the outdoors and went on to guide and instruct for organizations like Outward Bound. He now teaches mountain biking at Appalachian State University and has become one of the pivotal members of the Boone riding community, helping to design and execute plans for Rocky Knob Mountain Bike Park in town.

His wife Alecia, who has also worked at Outward Bound and now teaches at the university, is an endurance trail runner on top of being a full-time mom, advisor, and professor. Endurance training translates to six hours a week running in the woods when she’s not teaching or helping Kristian care for their two children—nine-year-old Silas and six-year-old Jude. Despite their hectic schedules, Alecia knows that time outdoors is non-negotiable, both for her children and herself.

“This time and space [in the woods] is important and I protect it,” Alecia says. “There is nothing more fulfilling than a long trail run under a canopy of trees, accompanied by birds, chipmunks, and the occasional deer.”

While Silas and Jude don’t necessarily share their mother’s fondness for long-distance running, they certainly exhibit her love of the outdoors. Mostly though, it’s their father who they best relate to, particularly when it comes to playing outside.

“Why do you like riding bikes?” Kristian asks his oldest, Silas.

“Because they can get you places faster than walking or running and it’s fun,” Silas responds.

In the past year, Silas has started downhill racing nearby at Beech Mountain for a youth team based out of Banner Elk. Kristian says that, though he’s proud of both Silas and Jude for their interest in biking, it was never something he and Alecia had intentionally planned.

“If you asked me 10 years ago if my son was going to race mountain bikes, I’d say, ‘No, I don’t want him to,’” Kristian says, “but you’re a product of your environment.”

“I want my children to have a relationship with the natural world,” Alecia adds. “It is necessary for my children to have a sense of their bodies in a wider space that is infinite—a deep connection to place is fostered in outside enjoyment.”

That connection to place is something both Silas and Jude have already adapted, despite their young age. When asked about their favorite outdoor activity, the pair responded with the same answer: riding bikes at Beech Mountain and Rocky Knob Park, both of which happen to be in their backyard.

“It’s to the point now where I’m definitely seeing that there will be a day when they are faster and stronger than me,” Kristian says, with a tinge of sadness. “Just five years ago I was whining because I thought they’d never be big enough to ride trails and long distances. Now I’m not ready for that.”

Kristian and Alecia agree that, in an age when technology has become nearly inescapable, finding balance is one of the biggest challenges of parenting.

“It’s easy to cite the interference of technology as an affront to being in the outdoors,” Kristian says. “Today we, not just kids, are all easily enamored by our gadgets. Our challenge as a family is more about balance. Being outdoors for us means learning about and being subject to the natural world and its timeline, but this is often in conflict with schedules—school, soccer, piano, art. Even when we’re out biking, it’s often [during] a structured time with obligations at either end. It’s hard within this structure to be in tune with the outdoors.”

Though both Kristian and Alecia work hard to instill the importance of nature in their children’s lives, sometimes the simple act of discovery is lost in the commotion of day-to-day life. During a recent outing however, Kristian says Silas reminded him of that very thing when they stopped mid-ride to fix a flat. Silas, who noticed their pit stop happened to be in a field full of buckeyes, began collecting the flowers in an effort to gauge how many buckeyes could come from one pod.

“At first, I saw our riding time disappearing,” Kristian says. “Then I saw the inquiry and was reminded that mountain biking should be as much exploration of the natural world as distance or achieving goals. This is one of the great rewards of parenting—children will teach if you let them.”

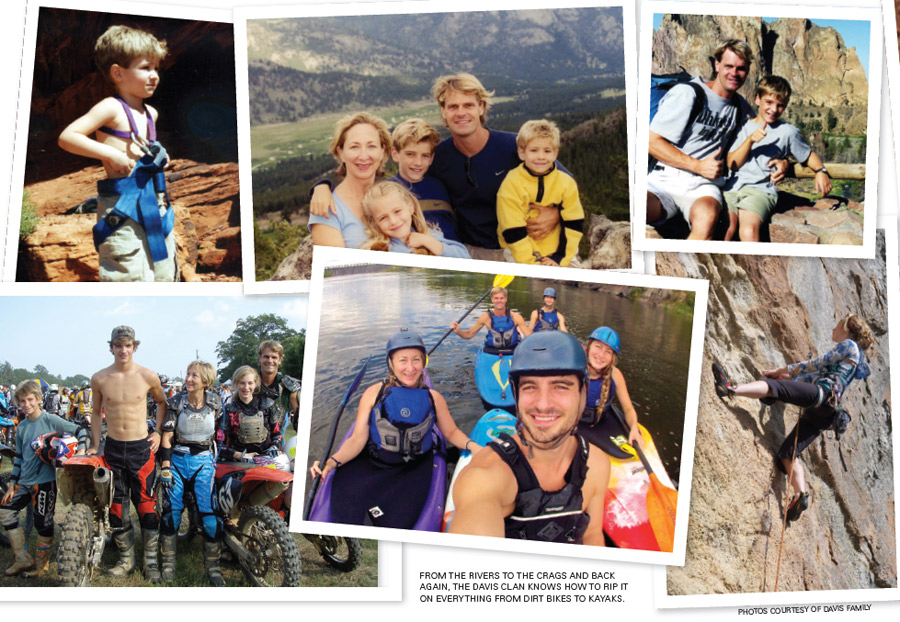

The Davis Family, Birmingham, Ala.

Dusty Davis never went camping as a kid. His father wasn’t outdoorsy. His mother, the quintessential Southern belle. So how did this Alabama boy go from a relatively traditional childhood to becoming the Oregon state mountain biking champion and an accomplished climber, kayaker, and all-around outdoorsman?

“Boy Scouts,” Dusty says. “But I also had a brother and we were always doing stuff outside. We’d find a piece of wood, build a ramp, and jump our bikes off it till we broke something.”

It’s that spirit of adventure, that scrape-your-knee method of learning, which steered Dusty throughout his early 20s. From Falling Creek Camp in western North Carolina to the University of Oregon, Dusty and his wife Mary Lou were able to work for a number of organizations that fed their passion for the outdoors. When they weren’t working, the couple was traveling through the West to climb some of the tallest peaks in the country, from the 14ers of Colorado to the big walls of California.

In the late ‘80s, both Dusty and Mary Lou took a break from the climbing scene to begin cycling competitively. Although Mary Lou gave birth to their firstborn son, Cole, shortly after in 1990 and had to discontinue competing, Dusty kept racing.

“[Having Cole] was fun and novel at first,” he says. “We traveled around, just the three of us. It was a blast. But after we had two more kids, Mary Lou didn’t come to races quite as much.”

It was in 1996, at the peak of his career, after claiming two back-to-back Oregon state championships in mountain biking and securing a name for himself among the upper echelon of riders (so much so, in fact, that he was asked to carry the Olympic torch in Atlanta), that Dusty decided to quit it all and focus on one thing: family.

“The nature of racing is that you can’t halfway do it,” he says. “You’re either in or out. At times, I’d think ‘how did I ever give this racing up?’ but there are times for everything.”

With rigid training schedules and weekend competitions out of the way, Dusty and Mary Lou were able to put that free time toward strengthening their family’s bond. From the crags to the rivers and back again, Dusty and Mary Lou were rarely seen without their three children—Cole, Honey, and Cricket—in tow.

“I think there are a lot of myths about having kids, like ‘oh it will change your life,’ or something,” Dusty says. “But we just grabbed their car seats and took them to the rocks with us. It was harder, but it was fun seeing their eyes of wonder.”

Now 19, the middle child and only daughter, Hannah (or Honey as she is mostly known), has grown into a young woman who truly embodies that sense of childish wonder. Proficient in climbing, mountain biking, and dirt bike riding (just to name a few), Honey’s badassery lies beneath the surface of a humble and loving persona that matches her nickname. Honey takes after her parents in that, when she’s not in school, she’s working for Camp Illahee, the sister camp to Falling Creek where her father began developing his own love of adventure sports.

“I have some of the best parents ever,” Honey says with pride. “I love how real they were with us, how they included us in everything fun they did. They brought us up together to be best friends.”

“We actually chose to not ever have a TV,” Dusty adds. “Doing things with other people is so important—that’s how relationships really get forged. If we’re outside having to solve problems together, maybe we had to deal with mosquitoes or pick ticks off each other, or maybe we ran out of food, but we do all of that together. I think those experiences do way more than just dropping the kids off at practice.”

Honey says that growing up with such a lifestyle was liberating and, surprisingly more fun than hanging out with her girlfriends even. But that’s not to say there was anything easy about it.

“One of the challenging things [about my childhood] was learning to be tough,” she says. “In the end, it taught me that there are bigger things than scrapes and bruises. Now I love that feeling of pushing yourself to your limits, but also overcoming and failing and learning to pursue and continue on.”

From slacklining and snowboarding in New Zealand to surfing in Mexico and regular weekend climbing trips to the Linville Gorge, whether all five members of the Davis clan are together or not, one of them is doing something outside nearly every day. But it’s not just about shredding power and sending routes that are important to the Davis family. Though that was certainly a byproduct of their outdoor excursions, Honey says that one of the most important lessons she took away from her parents’ guidance was that through the outdoors, one could continue to be a student of life indefinitely.

“Bringing us outside and doing adventures with us was such an escape from an otherwise mundane life,” she says. “It took you out of your box, out of your suburban bubble. [My parents] prepared me to go out into the world and not be so self-focused, so caught up in this small view of the world, and to be more free from it.”

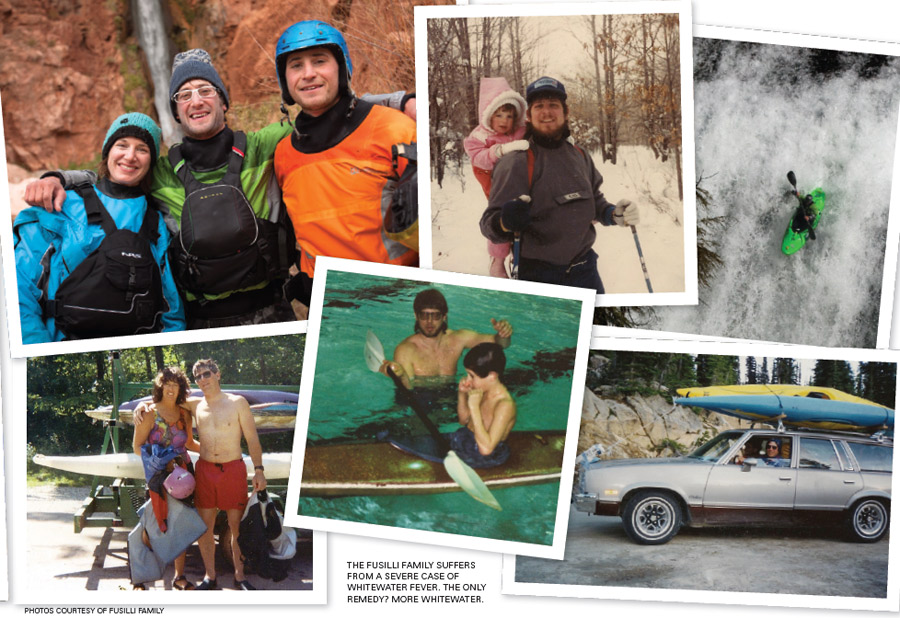

The Fusilli Family, Clarion, Penn.

When you grow up on the river, chances are you’ll never leave it. At least, that’s how it’s been for David, Carly, and Rob Fusilli.

“To my knowledge, Dad wanted us all to be kayakers,” says David, a professional kayaker and team manager for Pyranha Kayaks.

“I’ve always been supportive of it,” adds David’s father, David Sr. (more appropriately known as Big Dave). “We hoped that he would hit big with it and do well and he has. But in anything that you’re doing, you gotta progress and take the next step.”

Big Dave is no stranger to that progression or the numerous class V steep creeks and high volume rivers that his kids have been paddling for nearly 20 years. In fact, Big Dave was the first Fusilli to catch whitewater fever. In the mid-‘70s, he enrolled in an introductory kayaking course taught by paddling legend John Sweet (for whom Sweet’s Falls on the Upper Gauley is named). From there, he slowly built upon his skills on the Lower Youghiogheny River in a homemade fiberglass boat.

“It was not an easy thing to get into back in those days,” Big Dave says. “I sorta did it by myself.”

Big Dave came to kayaking later in life than most. By the time he was upping his game and paddling harder runs like the Upper Youghiogheny, Big Sandy, and the notoriously dangerous Upper Blackwater, Big Dave was over 30. His wife, Kris, enjoyed joining her husband on rafting trips and had even gained enough boat maneuvering skills to paddle the Lower Youghiogheny. In all, she supported Big Dave’s newfound love—“except the time I was pregnant with David and he left me to go paddling while I was in labor,” Kris says. “He just said, ‘I’ll be back in a little bit. You’ll be okay.’”

“Ah come on, it was Mill Creek—it was just over the hill!” Big Dave cries out in defense.

The year was 1981. Soon after, Carly and Rob were born, and Big Dave decided to change his focus from developing his own skillset to fostering a love of kayaking in his own children, a mission he tried in vain for the first 18 years of their lives.

“I was scared of kayaking early on,” admits Rob, the youngest of the three. “I remember swimming and getting knocked over by a tree limb and not being able to get out of my boat—”

“Well, that’ll happen when you’re eight years old,” Big Dave intervenes.

“We used to take kayaking clinics on Slippery Rock nearby,” continues David. “The instructor was making us peel out into the current and I remember being scared. Everything I paddled with was beater. The skirt was homemade, the boat was homemade, the life jacket, the helmet…”

“I’m still afraid of Slippery Rock,” Carly chimes in. “Every time I get on that river, I’m eight years old again and hating kayaking.”

Most of the Fusilli family’s memories of boating sound a lot like this and are riddled with entertaining tales of epic floods, questionable judgment, and, ultimately, one-helluva-good-story. Though the children were initially resistant to joining their father and his paddling buddies on the water, they had a change of heart after high school, especially once David started raft guiding locally on the Youghiogheny River. Carly and Rob were quick to follow David’s example, and both David and Rob would go on to guide out west on the Arkansas for a number of seasons.

Since then, the three Fusilli siblings have continued to paddle together, whether it’s stand-up paddleboarding in their stomping grounds on the Clarion River or cranking out a 14-day self-supported kayaking trip through the Grand Canyon. Though initially the one who liked kayaking the least, Rob in particular has taken leaps and bounds in his paddling career and regularly accompanies his older brother down some of the most difficult runs in the East.

“Rob and I have been paddling the hardest stuff we can find, and it’s special but it’s kinda scary too,” David says. “The most fun times I can think of are the runs I know Rob’s kicking ass right behind me.”

“A love of adventure is kinda embedded into us,” Carly adds. “We’re never on the beaten path.”

David joined Pyranha Kayaks’ elite paddling team in 2006 and has been touring for the company ever since. He’s kayaked all over the United States as well as Canada, Chile, Argentina, Austria, Ecuador, and Uganda. His most recent claim-to-fame came in 2013 when David executed the perfect rescue above a 60-foot waterfall, saving his friend and fellow team member Bren Orton from a likely fatal swim. David happened to be filming with his GoPro at the time and captured the entire rescue, a video that went viral in the span of 24 hours.

“We all grew up in a cemetery,” David says in reference to the Fusilli’s family business. “We’ve all dug graves our whole lives, so I think subconsciously, it for sure affected us. Our parents taught us that you better get out there and enjoy yourself.”

“That and to not be crybabies,” adds Momma Fusilli.

The Chase Family, Davis, W.Va.

It’s nearly impossible to mention teleskiing in the East without hearing one man’s name time and again: Chip Chase. He’s the head honcho at White Grass Ski Touring Center in Canaan Valley, W.Va., and has been helping visitors to White Grass get on cross-country skis since the center’s opening in 1981. While Chip is certainly the face of White Grass, at its core is his powder-loving family and, in particular, his three sons—Cory, Adam, and Morgan.

“From the first time they walked, they skied,” Chip says. “They were skiing in the womb, then they were skiing on my shoulders, then on our backs.”

“There are pictures of us walking around the house in skis,” adds Cory, the oldest brother in the family.

“Skiing was one of those things where it was like second nature,” says Adam, the second oldest of the crew. “It’s so innate.”

Chip came to Canaan Valley in the late ‘70s with a Vermont-bred love of telemark skiing already instilled in him. Two years after he and his wife Laurie (the White Grass Café chef extraordinaire) opened White Grass, Cory was born and the touring center became entirely family-focused.

“Because we had kids that skied, it legitimized White Grass and helped us nurture the family,” Chip says. “We became a family-oriented operation through our own family. We were young when White Grass was young so we were able to streamline it right off the bat.”

Though the boys all tried their hand at both snowboarding and alpine skiing and even raced on the local ski team in Davis, there was something about the freedom of telemark that always spoke to them. Eventually, the boys started showing up to downhill practice in their teleskis, but when their coaches said they had to go alpine or go home, they went home.

“We’d get into trouble at practice because we’d be ducking into the treeline and jumping off stuff,” Adam remembers. “It seemed crazy that we were getting into trouble for just wanting to have fun. We weren’t super competitive—it was more of a lifestyle.”

Given the remote nature of Canaan Valley, that lifestyle was one that provided a lot of freedom, especially in the wintertime. Left to their own devices while Chip and Laurie worked night and day at White Grass, the boys passed the time by carving out snow tunnels in the drifts, building ski jumps, and pull-skiing (usually at night and with the help of a friend’s pickup truck).

“I remember being really young and hearing my dad tell us we could stay home from school, but only if we went skiing,” says Morgan, the youngest of the bunch.

Despite the fact that the Chase boys were practically raised on skis, they were not exempt from indulging in typical teenage boy pastimes like video games. According to their parents, though, Nintendo never stood a chance against a solid powder day.

“There was never an issue with too many video games,” Chip remembers. “It was a short-lived phase. Now, none of them are all into their phones. They’re computer-literate, but they’re balanced and it doesn’t eat them up.”

Instead of phones, computers, and televisions, the Chase boys had something astronomically more valuable: they had people. They had live music, reunions with old friends, celebrations with new ones. There was never a dull day at White Grass during the winter. Even after a long day at the lodge, Chip would always make time to take the boys out for a night ski, usually under the light of a full moon.

“No headlamps needed,” Cory adds. “The mountain was ours. That’s when you realize how lucky you are to have been raised in a Nordic heaven.”

The boys all agree that those rowdy nights spent at the café eating their mother’s food and watching their father work the crowd were equally special to them as the long hours of quiet bliss skating beneath the stars. Though it would seem logical for the Chase boys to move on from Canaan Valley and become sponsored skiers or even ski instructors, they’ve all chosen to keep their passion for skiing as such.

“I inherited skiing as a tradition and that will always be in me,” Morgan says. “Any time I’m on my skis, I’ll be tapping into my home and my past, and that is such a beautiful thing.”