A New Year’s Adventure at Georgia’s Wild National Seashore

The trip began with a whiteout. I WAS paddling my packraft down the middle of the Crooked River, watching the fog thicken around me. My fatbike was lashed in thirds to the deck, and somewhere beyond, in the swirling whiteness, was Cumberland Island.

After three miles, I tepidly paddled out from the river channel into Cumberland Sound. Soon I couldn’t even see the shore behind me. Hearing the whirring motor of an approaching boat, I swung my red paddle blade over my head.

“Hey, I’m in the water here!” I shouted.

The motor throttled down, and I heard the boat slosh to a near-halt. The faint outline of its hull emerged from the mist nearby. Then it turned and zoomed away into the fog. Phew. That was close.

Bike-rafting to the largest barrier island in the Southeast was not my original plan. There are no roads to Cumberland Island National Seashore, just an NPS-affiliated passenger ferry from the quaint town of St. Mary’s, Ga. Once arrived, most visitors hike or backpack on the sandy roads and trails that cross the 18-mile-long island. But bikes are also welcome most places except a few interior foot paths. Pockets of private land remain on the slightly developed southern half of the island, which also has a seaside campground. Meanwhile, the northern half is designated wilderness, where a few primitive campsites can be reserved.

Given this would be my first visit to Cumberland Island, the original plan was to take my fat-bike on the ferry and bike-pack around for four days over New Year’s. But then a government shutdown suspended the service. In my living room, I had pumped up my whitewater packraft and disassembled my fatbike into pieces. It would be a tight fit, but it seemed manageable. The paddle-out from Crooked River State Park was about five miles through channels known for four swift tides per day. With printed maps and tide charts, I hit the road for Georgia.

In the fog-filled Cumberland Sound, I paddled onward, hoping for any glimpse of the island. After a quarter mile that felt much longer, a squat bank of tidal muck and reeds appeared. I exhaled in relief and followed the shoreline north. After accidentally turning down the wrong side channel, I fought the current back into the main channel. Luckily, I soon found a series of buoys leading to the dock at Plum Orchard. As I approached, an empty private vehicle ferry was departing.

While I carried my equipment to a picnic table, an armadillo playfully snacked on insects in the grass. Nearby was the impressive Wild Plum mansion, once owned by the Carnegie family, steel magnates from Philadelphia. After a debate over conservation versus development, in 1972 the heirs sold most of the island to the National Park Service. While switching from boat to bike, I watched a pair of SUVs arrive—visitors taking advantage of the shutdown to explore the island in private vehicles.

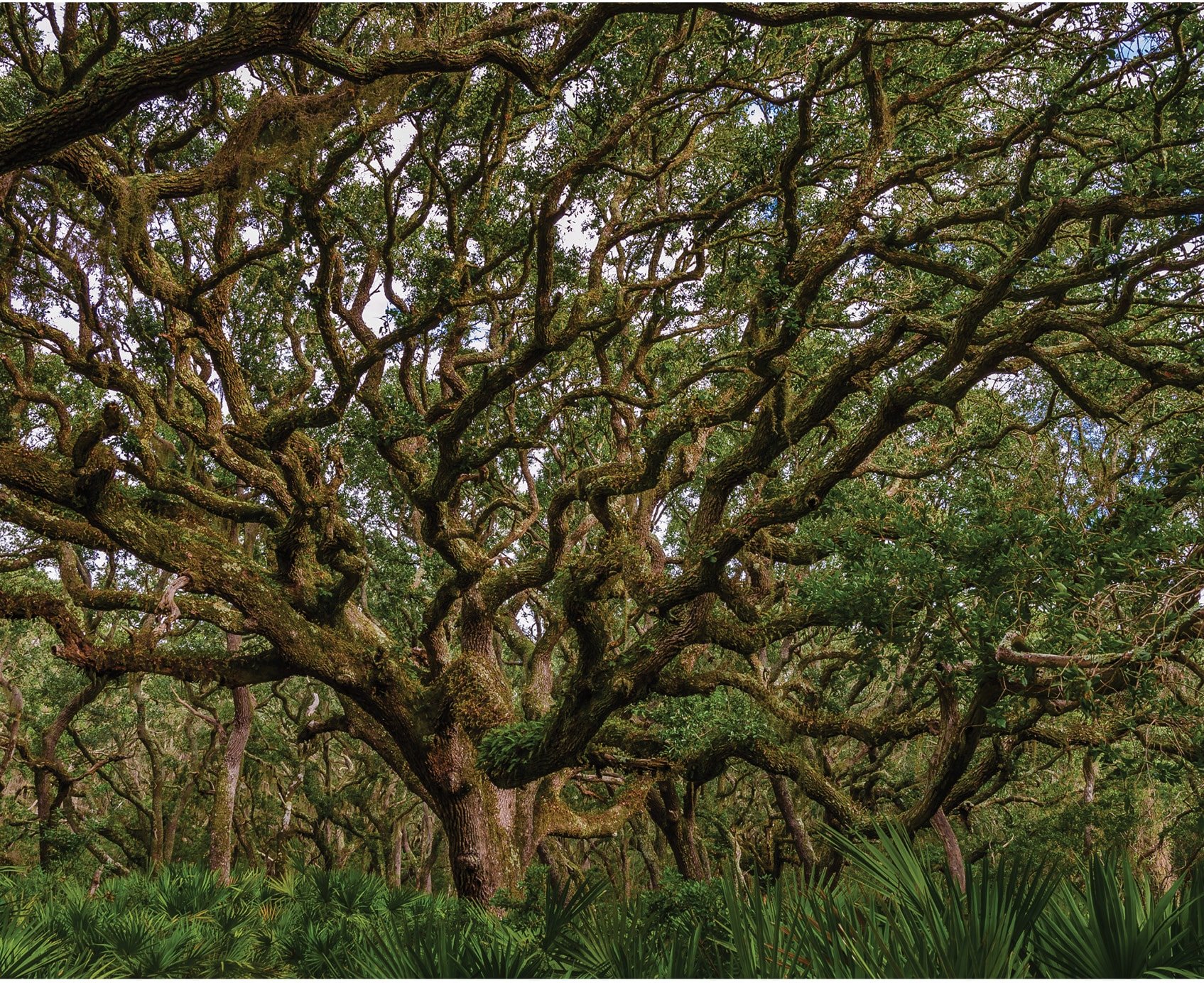

With my fatbike rebuilt, and my gear packed into bike-packing bags, I rode north on the sandy main road into the wilderness, still shrouded in fog. It’s one of the few such areas where bikes are allowed to ride through. Emerald saw palmettos lined the tunnel-like roadway, while massive live oaks, with salt-pruned branches draped in Spanish moss, arched overhead.

At Brickhill Bluff, I set up a primitive basecamp with my backpacking tent and chair. While pumping water from the well, I met my only neighbors, seven sea kayakers who had also paddled from Crooked River State Park for the holiday. Hanging out together that night, we wondered if we were the only eight campers on the northern half of the island.

Early the next morning, I de-rigged my bikepacking bags and pedaled south on a day ride. Passing by Plum Orchard, I stopped to chat with two older birdwatchers. They had come over with their vehicle on a private ferry and now were admiring a roseate spoonbill and some juvenile storks in a tree-top rookery. Their astute grandchild pointed at dense algae floating on a freshwater pond, where supposedly a 14-foot alligator sometimes lurked around the edges.

“That’s not very fresh,” the boy commented.

I next met four recently arrived canoers who, like me, had brought a copy of “Untamed: The Wildest Woman in America and the Fight for Cumberland Island” by Will Harlan. The book tells the story of Carol Ruckdeschel, who lives in a ramshackle compound near the northern tip of the island. A self-taught biologist, she studies local sea turtles and has long advocated for preserving the island.

When I continued south on the main road, an oncoming ATV whizzed past me. The driver was an older woman, grinning and waving, wearing a floppy fishing hat folded back from the wind. Wouldn’t you know? It was Carol Ruckdeschel.

Reaching the southern half of the island, limited signs of development appeared. A line of planted oaks overhanging the road like arched streetlamps. The restored buildings of the Stafford Plantation, still owned by a Carnegie descendent. In the clearing for the old airstrip, a few wild horses grazed while others galloped. Two young cyclists, riding rental bikes, stopped to say hello. They were staying at the Greyfield Inn, the only private lodging on the island. Curious, I turned in there next, finding a high-class estate of manicured lawns and cozy cottages. After learning the price to stay, I quickly rode away.

The southern road seemed less wild than its northern counterpart but equally impressive. In the bushes, armadillos startled and jumped. A few more private vehicles passed, but everyone was well-behaved, friendly, driving slowly with heads out the windows, awestruck at the scenery. Reaching the end of the road, I pedaled through the open gates of a formerly wealthy estate.

The ruins of Dungeness were once the largest mansion on the island, rising near its southern tip. The mansion burned in 1959, allegedly by arson. Where once there were windows, now there are empty rectangles and naked brickwork—yet another metaphor for this remarkable and wild island. I imagined a raucous Great Gatsby-like party during the estate’s heyday in the early 20th century, the halls and grounds overflowing with people. A single photographer, with a flashbulb camera, perched on a ladder above the gushing fountain.

I really wanted to capture a photo from that same vantage point (minus all the flappers—the island seems perfect as is). So, I picked up a massive palm frond, fallen from a recent storm, and attached my camera with a GorillaPod. While the timer went off, I tried to minimize the sway like I was hoisting a gymnast. Just then, of all moments on this nearly empty island, a couple walked by and stared at me like I was a 1959 arsonist.

The next 48 hours were a blissful blur. On my way back to camp, I checked out the Sea Camp campground, already planning a return trip with my wife and friends. For the first time in my adult life, I didn’t stay up until midnight on New Year’s Eve—instead I rested up for another day trip. Some mornings, I saw the dorsal fins of frolicking dolphins rising in the Brickhill River, just outside my tent.

I rode the beach to the northern tip of the island. Swam in the ocean. Hiked trails through the woodland interior and coastal pine forests. I visited the Settlement, where a small community of African Americans lived after emancipation. I may have mildly tried to stalk Carol Ruckdeschel, but we never crossed paths again. Instead, I bumped into a raft guide I met years ago at the Gauley—he and his partner had the same idea and canoed out for a wilderness weekend.

One day, hearing piano music coming from inside Plum Orchard mansion, I stumbled upon an NPS volunteer behind the keys. She’d stayed on the island to work for free, just like she always did.

“It’s kind of a free for all right now,” said the volunteer, shrugging off the private vehicles, which kept to the main road and beach. “But that’s fine, something different. Everyone’s behaving.”

She was right. On an island with a daily limit of 300 visitors, I saw maybe 50 people per day during the New Year’s holiday shutdown. And unlike a few other parks around the country, I never saw any evidence of opportunistic vandalism—a very welcome sight.

On my fourth day, I shoved myself into that tiny packraft. Then I reluctantly shoved off, with lashed fatbike, into the tidal current. My bike-rafting trip was sadly over. But as luck would have it, only 10 months later, with my wife and three friends, I’d be back.

Cover Photo: Photo by Mike Bezemek