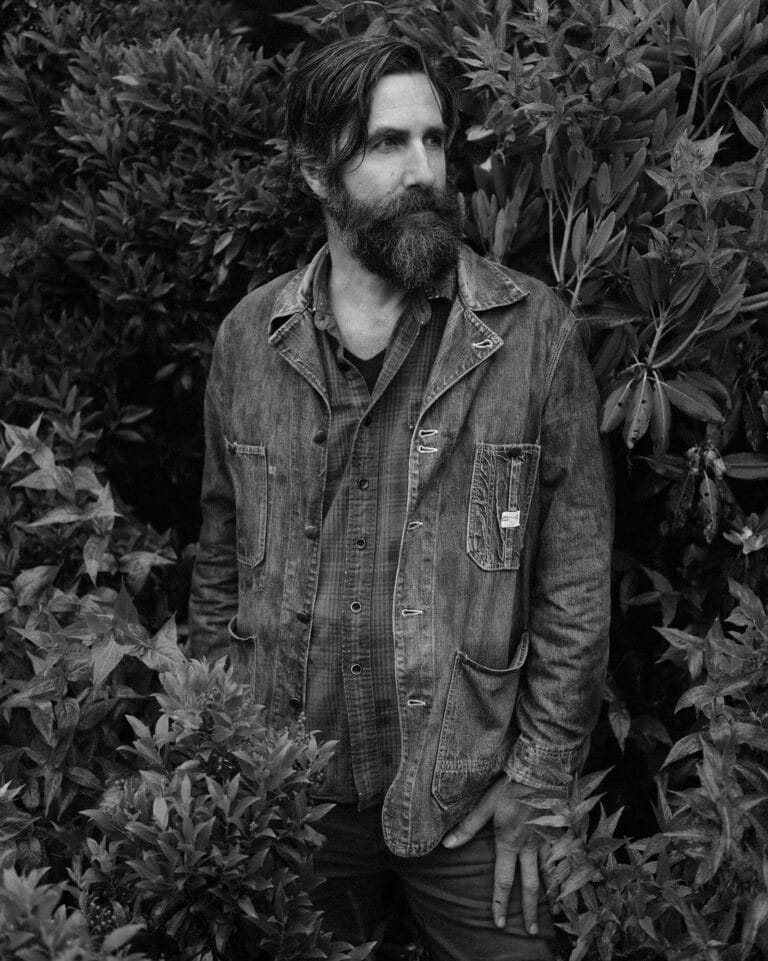

Bleak future: During the winter of 2016-17 some resorts in Italy’s dolomites had as few as six snow days. As Snow droughts, or consecutive winters with less than one-quarter of the historical snowfall, become more prevalent across the planet due to climate change, ski areas will be forced to wind down operations. / Photo courtesy Protect our Winters.

The latest major climate report claims that the future of skiing and snowboarding is “unviable.” Will this finally inspire the industry to get political and demand action?

The word cryosphere, from the Greek word krýos, refers to the Earth’s frozen zones. Used by scientists since the early 20th century, this previously little-used term is now entering the mainstream lexicon. Why? Climate change.

The cryosphere, from polar ice to mountain glaciers and snowfields, is literally weeping.

For skiers, the latest sobering news came with the release in late September of a major report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, the “Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate.” While media coverage of the report largely focused on the decline of ocean ecosystems, rising sea levels, and unprecedented melting in the Arctic, a small subsection detailed the threats to mountain tourism, including skiing and snowboarding.

“At the end of the century,” if humans continue to emit greenhouse gases unabated, “snow reliability is projected to be unviable for most ski resorts under current operating practices in North America, the European Alps and Pyrenees, Scandinavia and Japan, with some exceptions at high elevation or high latitudes.”

“Unviable” is the descriptor that should concern skiers and snowboarders who care about the future of their sport—and of mountain ecosystems in general. The report’s findings mean that skiers “may not be able to teach their grandchildren how to ski at their favorite resorts where they learned how to ski,” says economist Marca Hagenstad, a contributing author to the skiing section of the IPCC special report.

The IPCC’s findings once again highlight the profound importance of implementing the goals of the Paris climate accords, according to Hagenstad, lead author of the 2018 report “The Economics of Snow in a Changing Climate” from the climate action group Protect Our Winters. The Paris agreement, which the Trump administration backed out of, calls for reaching carbon neutrality by 2050 with the goal of keeping global warming to 2 degrees Celsius. The snow sports industry faces uncertainty even if humanity succeeds in hitting that target, but Hagenstad thinks it could survive. Inaction, however, will be “disastrous.”

Snow Droughts and Worse

The IPCC report adds to the drumbeat of studies that show the bleak future facing snowsports on a warming planet. Season lengths could shrink by half by 2050 and 80 percent by 2090 in the United States, according to the 2017 report “Projected Climate Change Impacts on Skiing and Snowmobiling: a case study of the United States,” published in Global Environmental Change. The study concluded that “limiting global greenhouse gas emissions could both delay and substantially reduce adverse impacts to the winter recreation industry.”

A study published in August in Geophysical Research Letters found that “snow droughts” in the mountains of the western United States will become more frequent. The authors defined snow droughts as two consecutive winters with less than a quarter of the historical snowfall. Snow droughts are currently rare, occurring only about seven percent of the time, but within a few decades they could occur about 42 percent of the time, says the study.

Snowmaking is crucial to ski areas, allowing them to open before the important Christmas holiday period. But you can’t blow snow when it’s warm. “Within the next 20 years, the number of days at or below freezing in some of the most popular ski towns in the U.S. will decline by weeks or even a month,” says a Climate Impact Lab report.

“If global greenhouse gas emissions continue to rise at the same pace that they did in the first decade of this century, ski resorts could see half as many sub-freezing days compared to historical averages by late century.”

The ski industry has been constricting for decades, with the number of resorts in the United States declining to 460 from about 700 in the 1980s, and “lower elevation resorts are already challenged with more rain in winter and shorter seasons,” particularly in the Northeast and Midwest, Hagenstad says.

“The reality is that the IPCC report confirms what we already know,” says Lindsay Bourgoine, director of policy and advocacy for POW, whose 2018 report was cited by the IPCC. “This just ups the ante.”

Bourgoine recently traveled to Capitol Hill as part of POW’s annual climate lobbying day, when athletes and members of the snowsports community speak to members of Congress. She says this year marked a noted change. “Republicans are no longer denying climate change. They are looking for a way into the conversation. It’s a big dramatic shift. But while this change is heartening and exciting, we are up against a timeline.”

Don’t Cry for the Cryosphere—Act Up

For Auden Schendler, senior VP of sustainability for Aspen Skiing Company and a leading voice for climate action within snowsports, the ski industry has a choice: Make climate change a top priority or begin planning to “wind down” resort operations. “The question I have is: When does this become the number one issue for the industry?”

Resorts, equipment manufacturers, and snowsports trade groups must get more political, Schendler says, and they must reject climate denialism and obstructionism from political leaders—and within their own ranks. “We have to shame leaders who have no substantive climate action plans,” Schendler says.

In late September, public shaming and pressure from within the snowsports industry led the International Ski Federation, or FIS, the governing body for international competitions, to join the U.N. Sports for Climate Action Framework, which commits the group to not only reducing its own carbon footprint but more importantly advocating for climate action.

The FIS announcement came seven months after Protect Our Winters, Burton snowboards, and Alterra Mountain Company called for the resignation of FIS President Gian Franco Kasper after Kasper appeared to deny climate science by referring to “so-called climate change.” The protest campaign generated 9,000 letters to the FIS and “shows the power of speaking up,” Schendler says.

Individual skiers and boarders must communicate with the resorts where they buy season passes and let management know they want the resorts to use their business clout to push for action, whether locally, at the state or federal level, Schendler says. “We all need to push a bit harder.”

But politics is the most pressing issue. The big environmental improvements in American history have only come when government got involved and passed laws such as the Clean Air Act and Clean Water Act, before which rivers were open sewers and the air was unbreathable in some American cities. POW and its allies are now targeting the 2020 elections with the goal of getting members of the snowsports and outdoor recreation communities to go to the polls and vote for candidates that support climate action, such as carbon pricing.

POW feels that it can make a big difference by turning out just a few thousand skiers and snowboarders and climate-activist voters in swing districts and swing states.

“We believe there are lots of passionate outdoor people who care about climate,” Bourgoine says, “and we are going to make sure they vote in 2020.” She cited a recent poll from Western Priorities which showed that members of the outdoor recreation community are an increasingly powerful voting bloc.

Bourgoine points to the 2018 victory of Democratic U.S. Sen. Jon Tester of Montana as an example of how a few thousand votes can get a pro-climate-action candidate into office. The Protect Our Winters Action Fund, POW’s political action arm, blitzed Montana with digital, radio, and print ads in 2018 in support of Tester’s climate stance. The ad blitz, including a social media video from climber Conrad Anker calling Tester’s opponent Matt Rosendale a “Jerry” who doesn’t care about climate or the mountains, generated more than 1.3 million impressions, according to POW. Tester won re-election by 15,000 votes. While it is impossible to quantify how many of those votes were generated by the POW ad campaign, the result shows that “we don’t need a lot of people to swing an election,” Bourgoine says.

Margins of victory can be even smaller in U.S. House races. For instance, Ben McAdams, who supports strong action on climate change, won Utah’s 4th Congressional District representing Salt Lake City by a razor-thin margin of about 700 votes. POW’s political action fund, a 501(c)4 organization, will target districts such as this that President Trump won or lost by 10 points or less. Examples include the Grand Rapids area of Michigan. “That is an area with colleges and outdoor industry brands and an active outdoors community where a small number of pro-climate voters can make a difference,” Bourgoine says.

Protect Our Winters strategized on its 2020 swing-state campaign during its annual meeting in Moab in October. “The 2020 elections are a major deal where skiers and the snowsports industry can with a few thousand voters get a climate-friendly candidate into office,” says Schendler. He pointed to U.S. Sen. Susan Collins of Maine as a candidate who has been “wishy washy on climate” who could be susceptible if the state’s large community of snowsports enthusiasts goes to the polls.

Skiers worried about the cryosphere, and who live in hotly contested districts, could begin seeing POW Action Fund ads soon. Climate Jerrys beware.