When journalist Scott Carney set out for the Polish countryside in 2014, on assignment for Playboy magazine, he thought he was going to write an expose. He arrived to cover the extreme environmental conditioning habits and coaching of Wim Hof, a.k.a. The Iceman, whose unorthodox methods had enabled him to accomplish super-human feats, such as submerging his entire body under ice for close to two hours and climbing Mount Everest wearing only hiking boots and spandex shorts.

For a week, along with other tutees, Carney sat on ice blocks, stood in the snow barefoot, alternated between breath-holding and hyperventilation and moved through a series of tests to extend control over his previously untapped (and for the most part, untested) physical capabilities. “I did think that he was very potentially a charlatan who was preying on people’s desire for super powers,” Carney says of Hof. “There was no indication that his feats were anything other than genetic anomaly. I was pretty sure him telling people they could do it was going to get them killed. Me going out there was going to be a warning, but it turned out that he was able to do the things he said. And I could repeat them.”

Carney not only replicated them; the methodologies became a part of his daily life. And he was so intrigued by the results that he decided to expand his article into a book. Entitled What Doesn’t Kill Us, Carney’s new 223-page work details how extreme environmental conditioning, at both a macro and micro level, can help you in a variety ways, from controlling immune system processes to simply losing weight. And whatever your limits, you’ll probably discover an inner strength that you never knew existed.

The training—and the results–doesn’t come without pain, as we learn through Carney’s writing and the stories of other participants. But pain, Carney argues, is a sensation that we were created to withstand, and one that more people have attempted to explore through experiences like Tough Mudders, adventure races and Antarctic marathons.

“How did pain become a luxury good?” Carney writes. “Could it be that there is a specific sort of pain that might serve a hidden evolutionary function?”

Carney addresses that question throughout the book. As he points out, “it only takes a matter of weeks for the human body to acclimatize to a dazzling array of conditions.” And yet, “the vast majority of humanity today—the entire population that spends the bulk of its time indoors and/or whose only experience when it gets too cold or too hot is wearing state-of-the-art outdoor gear—never exercises this critical system of their body.”

Evolutionarily, Carney writes, many, including 58-year-old Hof, would argue that we were made to withstand extremes in temperature, particularly the cold. But in today’s society of comforts, we rarely do so.

“Our bodies are not discreet things,” he writes. “Rather, they are reflections of the environment that they inhabit.”

I, myself, was skeptical as I began reading. But as I continued through the book, I couldn’t argue with the truth in the testimonials, studies and anecdotal evidence offered by Carney., I’ve subsequently tried some of the practices on my own. Granted, I’m not running shirtless in 33-degree weather just yet, but I’ve practiced some of the recommended breathing exercises while also pushing my body into an environment of temperature discomfort (my house thermostat is set to 61 as I type this—and I’m not wearing a winter coat).

Carney himself, who lives in Denver, accomplished everything he set out to do while training with Hof, beginning with breathing exercises (with a goal of holding one’s breath for five minutes) all the way to climbing Mount Kilimanjaro wearing only a pair of shorts and boots for the majority of the ascent (note: Carney pointed out that he only made it to Gilman’s Point, just shy of the true peak, Uhuru, though he, Hof and one other participant did so in an incredible 28 hours and six minutes). The idea is that Hof’s training builds upon itself—the breathing exercises, for example, train the body to compensate for lack of available oxygen, which therefore better prepares you to ascend steep elevations in a minimal amount of time.

Still, there are dangers, as Carney points out. There are cases of those who’ve tried Hof’s methods or similar extreme techniques, independently and without proper training, and died. Hof can swim under sheets of ice in only swimming shorts for close to 50 meters; this incredible feat, however, was not done without years of training.

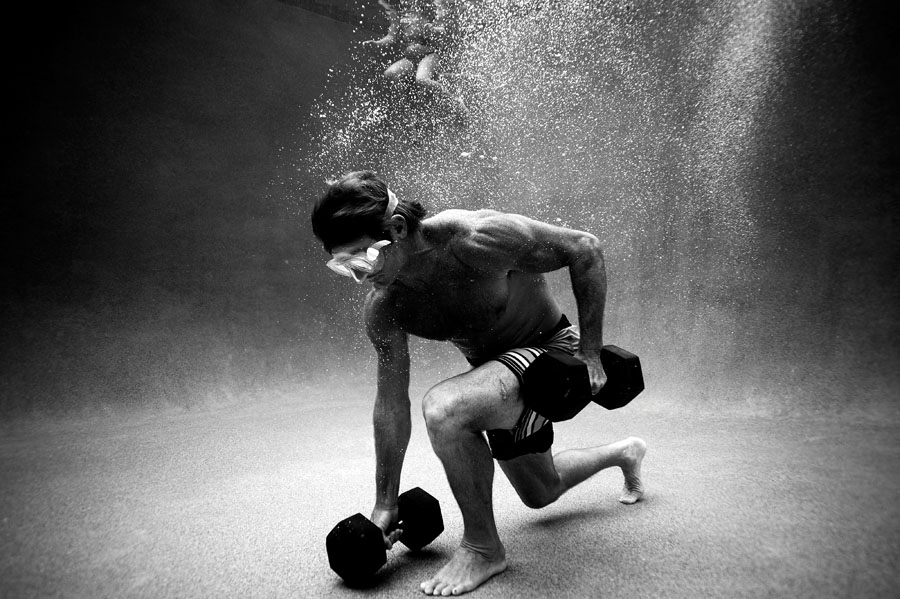

Following Carney’s week-long stay at Hof’s training site in Poland (for a $2,000 fee), he traveled the globe, speaking with scientists as well as trainers and other professional athletes. Carney devotes one chapter to the techniques of Hof-devotee and pro surfer Laird Hamilton—and finds that again and again, these methods produce results.

Scientific studies, too, often support this claim. As a 2014 study published in Trends in Endocrinology and Metabolism found, “Regular exposure to mild cold may be a healthy and sustainable way to help people lose weight.” (Of note: ‘mild cold’ is a bit different from the snowcaps and ice sheets where Hof undergoes his training).

A 2016 article entitled ‘The Surprising Health Benefits of Extreme Hot and Cold Temperatures’ notes, “Strategies that help optimize energy production in your body include exposure to extreme hot and cold temperatures, exercise…When exposed to cold, your body increases production of norepinephrine in the brain, which is involved in focus and attention. It also improves mood and alleviates pain.”

Carney discovered several people who’d reached a similar conclusion. Hans Spaans, who has spent the past 14 years battling Parkinson’s disease, decided in 2011 to spend several months training with Hof. Carney visited with Spaans at his home outside of Amsterdam in 2015. “Think of it this way,” Carney writes. “Parkinson’s disease is a degenerative process in which the brain slowly loses connections with the limbs it is supposed to command, and Spaans uses the Wim Hof method to strengthen environmental signals to override his failing neurology. It isn’t a cure. It’s a management routine. In 2015, he is enjoying 11.5 hours of ‘good time’ every day with a lower drug regimen as compared with 2011, when his daily average of ‘good time’ dipped to less than seven hours. And that progress is more hope than any doctor has given him so far.”

Carney also shares the story of Kasper Van der Muelen, a practitioner of Hof’s methods. After falling and breaking the ulna in his arm, which doctors predicted would require several surgeries and weeks of recovery, Van der Meulen healed in a miraculous three days (practicing Hof’s breathing methods and meditative practices), which the doctor described as “a medical anomaly.”

Carney acknowledges that perhaps all of the people he spoke to in writing the book were just that—medical anomalies whose bodies were built to withstand extremes, regardless of whatever methodologies they follow. “I mention in the book that that’s one of the potential problems-–that I’m meeting people who are doing the method; I meet the success stories and that’s certainly a limitation for the way I conducted sampling,” Carney says. “You’ll definitely find people who try the method and are like, ‘yea it’s not for me.’ You’ll find people who have more severe reactions to the cold – people for whom, because our systems are so degraded, it’s harder to learn the methods. But that won’t be the majority of people … I don’t want people to go out and get hurt, but I want them to realize that pain alone isn’t necessarily bad. That pain is a warning, and you should be aware of your warning, but still use your head and figure out what’s rational and real.”

When you do, as Carney illustrates throughout the book with himself (including regular visits to the CU Sports Medicine and Performance Center for testing) and others as case studies, you can push your body to new limits, increase your metabolism and achieve mental and physical breakthroughs that you previously considered impossible.

Perhaps most importantly, Carney highlights for the reader, in an easy-to-read-and-understand explainer within the chapter entitled The Wedge, how he/she can also incorporate a small-scale version of these exercises into daily life. So now, should you choose, you can try it. Who knows what you might find. Even if you don’t, the book is fascinating and will likely change the way you look at your environment—and your body’s capabilities.