The George Washington National Forest is home to the headwaters of the Potomac and James Rivers, which flow through two capital cities, Washington D.C. and Richmond, Va. One of the largest forests in the eastern U.S., it’s more known for its rolling hills blanketed with trees than it is for energy potential. But natural gas drilling, along with hydraulic fracturing, or “fracking,” could be coming to this wild forest.

The U.S. Forest Service originally disallowed horizontal drilling and fracking for natural gas within the George Washington National Forest boundaries. However, after pushback from the natural gas industry, the Forest Service began reconsidering. Hydraulic fracturing is exempt from the Safe Drinking Water Act, and companies do not have to disclose what chemicals they are using in the fluid pumped underground to bring gas to the surface. Some of the chemicals used in the fracking process could contaminate drinking water for many communities and poison some of the GW’s most celebrated rivers for fishing and paddling.

We tend to confuse our national forests with our national parks, thinking of them as pristine and unspoiled lands that are protected from commercial usage. But national forests are often subject to the same uses as private land, from cattle grazing to coal mining. Traditionally the most common commercial activity on national forests in the East was logging. Then, during the energy crisis of the 1970s, nearly all national forest lands in the East were leased for gas and oil drilling. Most attempts at conventional drilling came up dry. The gas deposits were too hard to get at using then-known methods. When energy prices began to fall, drilling for natural gas in the East no longer made economic sense.

Fast forward 40 years. America finds itself caught in a perpetual energy crisis. Politicians once again want the fuel under our feet, and public lands are seen as our salvation. New forms of drilling have now put the oil and gas resources beneath the Eastern public lands within reach. Much of the region’s drinking water comes from sources with headwaters in protected national forestlands. Will your drinking water soon be laced with fracking chemicals? Will your favorite forest campground or trail soon become a wasteland of wells, towers, and toxic ponds?

Fracking 101

America’s 21st Century shale gas boom has thrust hydraulic fracturing into the spotlight. “Hydrofracking,” as the process is known, is a catch-all term for a complex two-part method of natural gas extraction.

It starts with horizontal drilling. A well bore is drilled vertically for several thousand feet before turning horizontally and continuing for several thousand more. A water and chemical mix is then pumped into the well bore at high pressure. The fluid breaks up the shale rock and releases pockets of natural gas trapped there. Much of the fluids return to the surface and the “flow back” must be kept in containment ponds or hauled off site; the rest seeps into the groundwater.

The process of hydraulic fracturing has been used since the 1950s for making conventional vertical wells for oil, gas, and even water. The difference today are new horizontal drilling techniques and the massive amounts of water used—up to one million gallons of water per drilling site. Mixed with the water are toxic cocktail of chemicals—many of which are carcinogenic.

Drilling supporters say the process is nearly 50 years old and has been proven safe in many communities in the Midwest. Opponents point to known cases of groundwater contamination and spills, saying fracking threatens water supplies throughout the Southeast.

One thing is certain: fracking brings a large-scale industrial operation into wild lands. Roads must be constructed for the trucks that haul in fracking water, and pipelines are built to transport the gas to processing sites. A well pad, including its containment ponds, can cover up to 10 acres. When underway the operation, with its associated noise, light, and traffic, happens around the clock.

“The footprint of fracking is larger in scale and more disruptive than logging,” says Sarah Francisco, senior attorney at the Southern Environmental Law Center. “With logging, the forest regenerates, and in 100 years the trees will have grown back. But with gas drilling there is a permanent well pad in a permanent clearing.” Fracking usually involves many well sites and a much larger cumulative impact that leaves behind poisonous ponds, toxic waters, and a ruined landscape.

Public Lands, Private Profits

Who determines if gas drilling takes place in a national forest near you? First, an energy company requests to lease certain national forest lands from the Department of Agriculture, which manages the national forests. The Department of Agriculture then places the land up for competitive bid on a quarterly basis. Anyone can place a bid and the winning bidder gets a 10-year lease to explore for oil and gas. If they discover reserves, they apply for another lease and an extended permit. The government gets a small percent of the profit from the gas extracted.

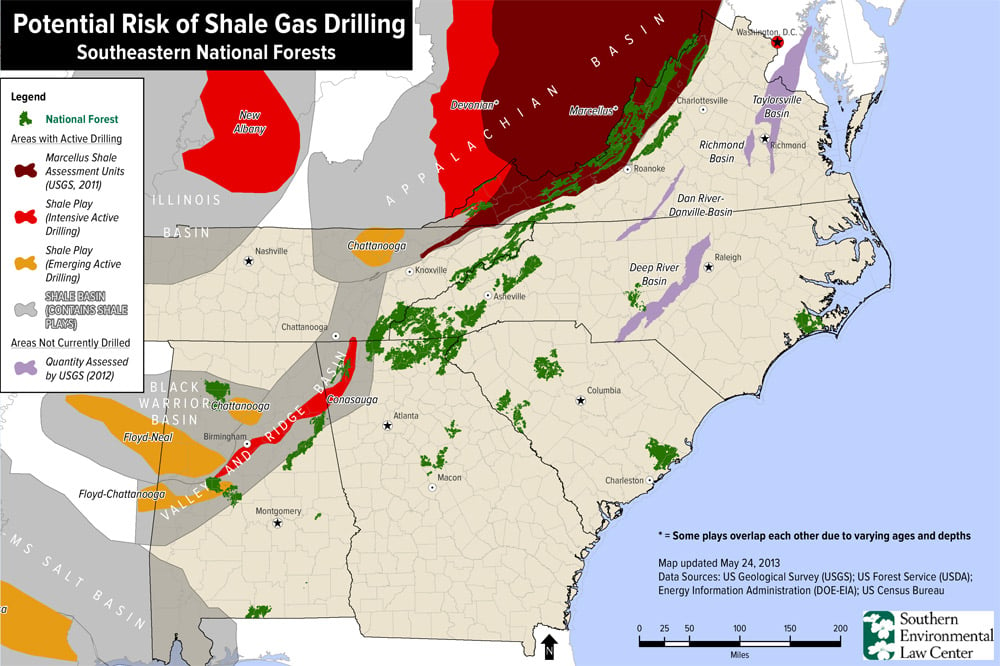

The Southeastern natural gas boom exists in areas that sit over top of the Marcellus shale beds, which include Pennsylvania, Maryland, West Virginia, Virginia, Kentucky, North Carolina and Tennessee. There are also known gas reserves in the Conasauga shale bed in Alabama, Georgia and Tennessee. The U.S. Department of Energy estimates the Marcellus shale alone contains 262 trillion cubic feet of recoverable natural gas.

There are approximately 8 million acres of public land in 17 national forests in the Southeast. Fracking has already occurred in two of these forests and is proposed for at least two more.

Pennsylvania has been ground zero in the Eastern fracking debate, sitting on top of the thickest part of the Marcellus formation. The Allegheny National Forest contains 500,000 acres and is home to more than 12,000 gas and oil wells.

West Virginia’s Monongahela National Forest’s 921,000 acres are open to drilling; a test well was drilled there recently in the Fernow Experimental Forest. And last year, Alabama’s Talladega National Forest announced that it would lease 43,000 acres for gas drilling.

The biggest concern is George Washington National Forest. At over one million acres, the GW is one of the largest undeveloped areas on the East Coast. Recently, the Forest Service began revising its management plan for the GW. Fracking opponents pushed for a prohibition on horizontal drilling in the forest. This was included in a draft of the plan before political and industry pressure forced to it be dropped.

“We developed options to allow horizontal drilling on forest land,” said Ken Landgraf, planning officer for George Washington National Forest. “Part of our job is to develop America’s energy resources responsibly.”

All national forests are administered by a management plan that is revised every 10 to 15 years. The GW is the first to come up for revision since fracking became prevalent. All eyes are on the GW.

“We are in the driver’s seat,” Landgraf stated.

A finalized management plan for the GW is scheduled to be announced this month. Meanwhile, other national forests are beginning to revise management plans, and fracking could be a major issue. Two of the most popular national forests in the Southeast—the Pisgah and Nantahala National Forests in North Carolina—are revising their management plans this year.

Areas of privately held mineral rights occur in all of the national forests. Ninety-three percent of the land in the Allegheny National Forest has its mineral rights in the hands of private companies. In the GW, 180,000 acres, or about 17 percent of the total land, has its mineral rights in private hands. Seven percent of the Talladega’s and 38 percent of the Monongahela’s acres have privately held mineral rights.

When the Forest Service tried to prevent drilling on these leases, they quickly ran into legal challenges. In 2011 a federal appeals court ruled that the Forest Service was misinterpreting its powers and had no authority to control access to private minerals on public lands.

“Companies have rights to their minerals [on private leases] and we cannot stop them,” Landgraf says. “But they do have to work with us [the Forest Service] jointly because they are using our surface.”

David and Goliath: Communities Take on Big Gas

With political will and industry money pushing for gas drilling in the national forests, what options do people who enjoy public lands and oppose fracking have?

In 2011 Carrizo Energy, a Houston-based company, applied for a drilling permit for a lease on private land in Rockingham County in the heart of Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley. The state quickly approved the permit. The county board of supervisors also seemed on the verge of signing off on the project. Then outdoor enthusiasts and local residents learned about the proposed well. They launched a campaign to educate the board and the community on the potential hazards of fracking. They were successful. The board tabled the permit, effectively preventing fracking on private lands in the county, which would include private mineral rights in the George Washington National Forest in Rockingham County.

Then in 2012, when Alabama’s Talladega National Forest announced it would sell fracking leases, outdoor enthusiasts vocally opposed it. The Southern Environmental Law Center filed litigation under the Endangered Species Act, and in June 2012, the Forest Service announced it would delay the gas lease sale.

It’s hard to say whether environmentalists won an outright victory or energy companies backed away from a fight in areas where gas production was uncertain. Nearby test wells in both areas failed to produce up to expectation. One thing is for sure: as the price of energy increases, supplies of petroleum dwindle, and technology improves, energy companies will keep the national forests of the Southeast in their crosshairs.

Wanna find out the latest news on fracking plans for the George Washington National Forest? Visit protectthegw.org.