The Unacknowledged History of the Land Beneath Our Boots

Whose land are we hiking, biking, climbing, and paddling on? When it comes to the history of public lands and conservation in this country, the Indigenous Peoples who once occupied those land are often left out of the conversation. Now, several mapping and preservation projects are telling a deeper story of the places where we play.

Starting the Conversation

A map tells a story about the relationship between people and the land. Through the key, scale, and compass rose, a map can tell us where we have been and where we are going.

But maps are only as accurate as the cartographer who makes them, often allowing for bias to influence how the map tells the story with labels and what, or who, is included.

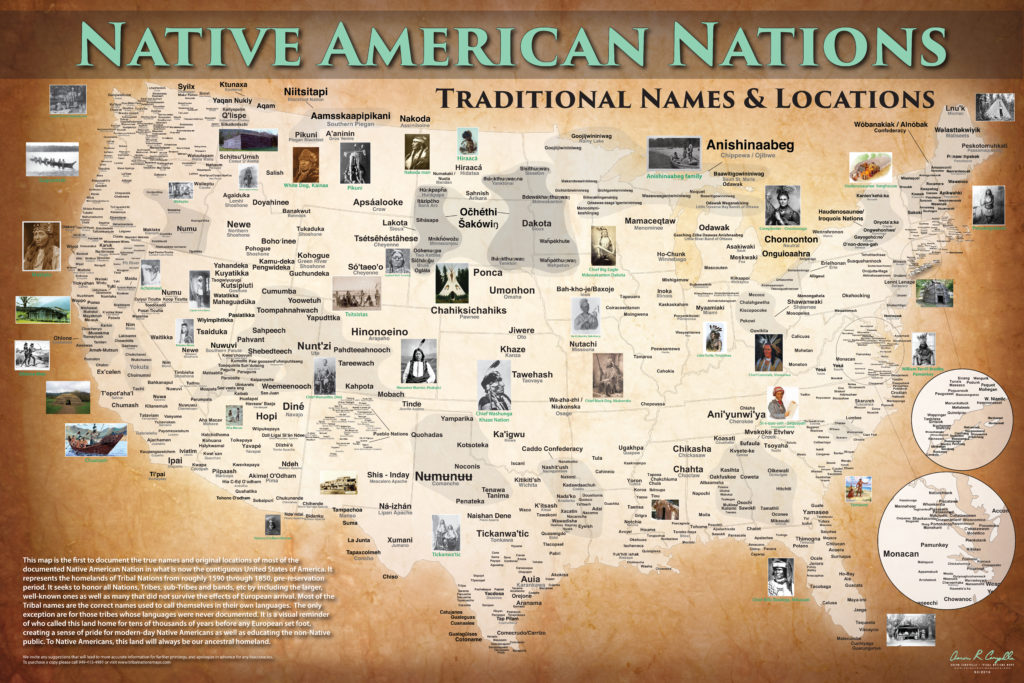

Aaron Carapella is working to change the narrative about Indigenous Peoples in this country through Tribal Nations Maps.

“As a kid, I would go to pow wows or Native American events and museums in California where I grew up,” he said. “I would find really basic maps with 30 or 40 tribes on them, mostly the common ones you would hear if you were watching John Wayne movies.”

Carapella found that most people didn’t know the land’s Indigenous history. A self-taught map maker, Carapella started designing his own set of maps to decolonize the way popular maps of the United States and tribal lands depicted Indigenous Peoples.

“Everyone wants to be represented. We all want to be seen,” he said. “Not in an egotistical or narcissistic way but recognized as human beings. This is where we’re from. I was trying to combat some of those other maps that were cheesy with caricatures drawn on them that were culturally incorrect. They would have a Seminole Indian with a headdress on whereas they didn’t dress like that.”

Carapella started out with a map of nations in the United States. Then he started getting comments from people in Canada saying he was using an arbitrary colonial border to cut off a nation from both sides of the border.

As he did more research, Carapella started offering a variety of maps, from Nations of the Western Hemisphere to more localized regional maps. He gives people the option to buy the maps with or without modern-day borders.

One thing especially important to Carapella in the creation of these maps was the use of names.

“Ninety-seven percent of the tribal names that you see are the common or colloquial names that were given either by another tribe or from Europeans,” he said. “Only three percent are the actual original name for themselves. As Europeans moved west, they would ask a tribe, “Who is to the west of you? Who are the next people we are going to encounter? What do you call those people?”

The maps include the commonly known names and traditional names like Ani’yunwi’ya (Cherokee), meaning the principle people, and Diné (Navajo), meaning the people.

“There’s power in taking back your own name for yourself,” Carapella said. “Many tribes’ names are specifically tied to whatever area they are from. Our very name is embedded into the place we live.”

For each nation represented on the map, Carapella works to have three sources for the name with the primary information coming from a tribal source. He has reached out to around 1,000 nations in the United States and Canada by phone, email, letter, or in person. As new information comes in, he makes sure the maps are as up to date as possible.

“I have this open policy that if I have a map in the incorrect place, the spelling has been changed by the tribe, or I’m missing a band here or there, I will always make regular updates,” Carapella said. “So, these maps have been a mission in progress. The ultimate point is to represent as many people that have been historically underrepresented on maps as possible.”

In 2016, at the time of the Standing Rock opposition to the Dakota Access Pipeline in North Dakota, he released a map detailing all of the proposed pipelines running through tribal homelands.

“There’s never just one pipeline,” Carapella said. “There’s never just one sacred site being discussed or litigated in court. There are so many pipelines that affect not only Native Peoples and cross Native territories, but it’s an issue for communities in general.”

Although he does sell the maps to cover the cost of printing, Carapella has donated hundreds of maps to museums, underfunded schools, and Boys and Girls Clubs so that the next generation has a better understanding of history and the present.

“They’ll talk about things like immigration, genocide, disease epidemics, which tribes helped in the Revolutionary War and Civil War, and all the different implications of that,” Carapella said. “The maps do prompt a whole lot of conversation.”

The pipeline map is available on Tribal Nations Maps’ website for free download to bring more awareness to current issues facing Indigenous communities.

“A lot of people look at Native People in a historical sense,” Carapella said. “Native people are still here, living and breathing. There are 100 tribes right now that are in litigation over pieces of their land. There are tribes that are fighting over sacred sites. There’s always tons of fights to get native people to be represented. It’s positive over time but there’s still lots of struggles. There’s a story to every tribe. These maps are only one small piece of the puzzle of us, as a country, realizing how many native people were here.”

He has now developed over 150 Tribal maps, postcards, and puzzles, representing 3,900 Nations and sub-Tribes throughout the Western Hemisphere.

Acknowledgement as the First Step

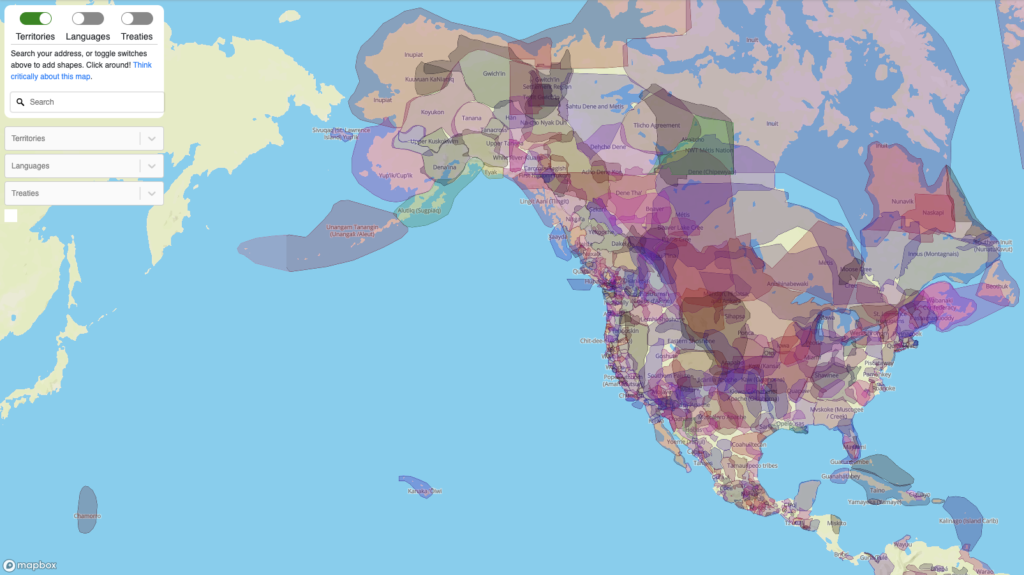

Victor Temprano was mapping resource management projects, including pipelines running through traditional lands, when he began to realize that mapping Indigenous territories was a project of its own.

“When I started, it was not that clear what exactly I was mapping,” Temprano said. “Was I mapping territory in 1492? Was I mapping territory today? You have many of the nations in Oklahoma now that weren’t in Oklahoma. So where should their territories be? Does that mean they’re not living on their own land? There are a lot of questions that go into that.”

Native Land is an interactive website and app that allows users to search by zip code or use geolocation to better understand the people, languages, and treaties that once governed the land they are on and, in many places, are still a part of the landscapes but often go unrecognized.

The overlapping outlines of communities illustrate the complexities involved with mapping Indigenous territories in the sense of what Westerners usually think of when it comes to states and boundaries.

“This is information that actually is about people,” Temprano said. “It matters. When you screw it up, it matters. So, if you draw someone’s territory wrong or you incorrectly write their name, that can be pretty harmful to some people and it’s important to pay attention to that.”

At the end of 2018, Native Land Digital became a not-for-profit organization led by an Indigenous Board of Directors.

“Myself, as a settler, it’s kind of a strange space for me to be running this project and in control of all those complicated decisions about who is Indigenous,” Temprano said. “So, I really wanted to have a group of Indigenous People who could debate some of these questions and explore different answers and make decisions about what is appropriate for the map.”

Shauna Johnson was working on her Master’s at the University of British Columbia where she met Temprano and learned about the project he was working on.

“I thought it was a really powerful tool,” she said. “At the time, I was learning about planning history and how land was taken away from First Nations people. Maps and drawing lines on maps was a really big tool that was used to do that. I thought it was a great idea, not only as an educational tool for settlers who don’t really know whose land they’re on, but also to empower the local communities to take the power of mapping and drawing lines into their own hands again.”

Johnson, who is Coast Salish from the Tsawout First Nation on her mother’s side and Tsimshian from Laxkwala’ams on her father’s side, said early explorers and settler governments used maps to invalidate Indigenous People’s claims to their own land.

“It was a policy for development by planners to systematically erase them from the land,” she said. “They mapped out where the resources were. They mapped out where Indigenous communities were in relation to those resources. And for the simple reason of wanting to gain profit from resource destruction, they would physically remove them from villages that they have lived in for centuries.”

As a member of the board of directors, Johnson is involved with shaping the future of Native Land. Moving forward, the board will look at questions of who gets put on the map, how to approach the map in a respectful manner that does not harm communities, and what other educational materials they might want to put out.

“I think the whole intention is to stimulate discussion in talking about the land,” Johnson said. “Whose land are you on? What is the history behind the land? What is the history of how those people got removed or were excluded or essentially erased from their traditional territory? How did that happen and how do we deal with that?”

In many places, national parks that we now use for recreation were created without the consent of the people already living there. Johnson said that in some cases, park management policies prevent Indigenous Peoples from ancestral practices such as hunting, fishing, and harvesting cedar.

“A lot of those people still live off of the land and survive off it,” she said. “It’s not just because they have to, but they want to. There are ceremonial practices that are also carried out and having that access to lands that are sacred or culturally important is really important for them.”

The app opens with a disclaimer that the map does not “represent official or legal boundaries of any Indigenous nations” and users should contact individual nations for more information. Temprano makes it clear that the map is not an academic level project and should not be used as such.

However, the Native Land app does help start a conversation about the history of the land. Land acknowledgements are a way of recognizing the people who lived on the land before colonizers pushed them out. This could take many different forms, from a spoken acknowledgement at the start of a conference to a written acknowledgment in an Instagram caption.

“It’s a pretty good step because it’s taking something that wasn’t ever visible or spoken and suddenly people are noticing it and trying to pronounce names,” Temprano said. “Even just thinking about it at all is a positive step. In my opinion, territory acknowledgements are useful early steps, but they can very easily become a token gesture because they don’t cost a lot to do.”

Moving forward, Temprano said the next step is to start forming actual relationships with Indigenous Peoples and organizations.

“Where are these people that I just acknowledged?” he said. “Where do they live? What is the situation? Are they fighting for legal rights? Do they have land? What use do they have of their traditional territory? Start asking those types of questions and see if that takes people somewhere. Because otherwise it just becomes another easy thing to say that has no power and it’s just lip service.”

Telling the Stories

Efforts to reclaim the history and names of Indigenous Peoples extends beyond literal maps of territories.

As a teller of Cherokee stories for more than 30 years, Kathi Littlejohn is reaching a new audience on YouTube with her series Cherokee History & Stories: What Happened Here?

With funding from the Cherokee Preservation Foundation through the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians Tribal Historic Preservation Office, Littlejohn has written and filmed ten short videos that tell a story at or near historic Cherokee sites.

“I am always looking for ways to get other people interested and to learn the stories to tell them themselves,” Littlejohn said.

In one episode, Littlejohn stands on the bank where the Valley and Hiwassee Rivers come together in what is present day Murphy, North Carolina. Cherokee speakers still refer to Murphy as The Leech Place.

“My biggest hope is to tell the stories and protect those sites,” Littlejohn said. “We literally go past them every day. I wish that people would visit the sites, feel what happened there, and then use the stories in their own lives. I think that anybody that realizes something happened right there gives them a deeper understanding of things that are happening now.”

Littlejohn, an enrolled member of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians, is now working on another ten videos focused on the Qualla Boundary. With the videos only running around five minutes and free online, she hopes the stories and history will be more accessible to more people, especially Cherokee families.

“People are becoming more aware and thinking history didn’t just start here with us,” Littlejohn said. “What happened here 180 years ago? What happened 11,000 years ago?”

Lamar Marshall, the cultural heritage director at Wild South, has also been working with the Cherokee Preservation Foundation and the Trail of Tears Association to map Eastern Cherokee trails and create an online database of the history and ecology of the region.

“If you were floating the Little Tennessee River or French Broad River, you’re following what was a Cherokee Trail on both sides of the river,” Marshall said. “Their trails were part of a continental wide network of trails that went from Hudson Bay to the Gulf of Mexico, from the Atlantic to the Pacific.”

Portions of these trails have become part of the Appalachian and Benton MacKaye Trails, but many have become overgrown or were abandoned. Using old maps and journals for his research, Marshall has also included information about the plants and animals of the area in the early 1700s.

“The ecology was incredible during that time,” he said. “There were buffalo all over the mountain. You had millions of passenger pigeons that would land in the trees. It wasn’t like the forest we have today. Every third tree in the mountains was an American Chestnut. When it died out, that took out 20 to 30 percent of mast that was in the forest. So, the bear populations were less, the turkeys and deer were less.”

Although he has been working on this project for decades, Marshall said there is still so much to learn.

“You could spend your whole life studying this and you would never even get started on it,” he said.

Museum of the Cherokee Indian

Cherokee, N.C.

Visit the Museum of the Cherokee Indian for more than 11,000 years of history, culture, and stories of the Cherokee people. The museum hosts Heritage Day on the second Saturday of each month with live music, traditional dancing, crafts, and storytelling.

Green Meadows Preserve

West Cobb County, Ga.

The Cherokee Garden at the Green Meadows Preserve features plants used by the Cherokee people of the region for food, medicine, tools, weapons, and shelter.

Noland Creek Trail

Great Smoky Mountains National Park, N.C.

Noland Creek Trail connected the Little Tennessee River Trail to Clingmans Dome, known to the Cherokee as Kuwahi or the Mulberry Place. Noland Creek Trail is also a section of the larger Benton MacKaye Trail.

Trimont Ridge Trail and Bartram Trail to Wayah Bald

Franklin, N.C.

The trail is maintained and in excellent condition. We recommend beginning at Wayah Bald and following the Bartram Trail route east to Bruce Knob where it leaves the Cherokee trail and ends at the Bartram trailhead at Wallace Creek.

Trail of Tears

Ga., Tenn., Ky., Ala., and N.C.

There are several sites along the Trail of Tears National Historic Trail open to visitors, including the Hiwassee River Heritage Center, Port Royal State Historic Park, and Mantle Rock Nature Preserve. These sites were stops along the route many indigenous people took during the forced removal from their land.