A small landslide on a crude social trail at Roanoke, Virginia’s Carvins Cove Reservoir in 1997 was the first in a chain of events that culminated about 20 years later in the Roanoke area being able to proudly call itself “America’s Mountain Bike Capital of the East”. What happened in the next few years after the landslide is a story of successful networking among usually disconnected user groups, social and political connections in a medium sized Blue Ridge Mountain community, “detective” work, a drought, activist citizens knocking on the right politician’s doors and progressive, forward looking and thinking by a few key elected and hired public officials.

Twenty nineteen will mark twenty years since the leaders of the city of Roanoke changed their thinking about the once threadbare and deteriorating recreation at Carvins Cove. More importantly for mountain biking, the intervening twenty years have seen remarkable planning and progress to upgrade Carvins Cove from being a 12,600 acre unpolished and underappreciated local wooded watershed to become a large regional mountain biking destination. The high point of the twenty year turnaround was the International Mountain Biking Association’s 2018 Silver-Level Ride Center Award to Virginia’s Blue Ridge. The VBR is centered on the city of Roanoke and extends about an hour drive in every direction. Carvins Cove is the crown jewel of the Virginia’s Blue Ridge mountain biking activity and more than any other feature of the area’s mountain biking, the Cove is responsible for the Silver-Level status.

A relative newcomer to the Roanoke area, Kristine McCormick came here nine years ago and fell in love with the living and mountain biking opportunities. It was probably her perspective as an outsider that gave Kristine the idea that we should be thinking a lot bigger than promoting the area to each other. Her vision coupled with her marketing and networking skills culminated in the Silver Center award.

Carvins Cove is seven miles from downtown Roanoke and literally seconds from Interstate-81. Surrounded by undeveloped mountains, the Cove is the largest municipal park east of the Mississippi River and the largest conservation easement in Virginia. The Cove’s primary function is to provide drinking water for the city of Roanoke from the 630 acre reservoir. Fourteen miles of Appalachian Trail skirt the Cove and McAfee Knob, arguably the most photographed feature on the AT, overlooks the Cove.

Today the Cove contains more than 60 miles of multiuse trails with more being built all the time. What will be, at seven miles, the longest flow trail in the world is being built at the Cove. Carvins Cove is a popular destination for equestrian trail riders, trail runners, hikers and mountain bikers. The Cove has five easily accessible access points and in the Fall of 2019 will be physically connected to the Roanoke Valley’s extensive Greenway paved trail system. In a few years a cyclist will be able to leave downtown Roanoke’s beautiful and historic Hotel Roanoke and cycle on the Greenway system to Carvins Cove without touching a public road or street.

All of this almost did not happen. This is the story of how Carvins Cove evolved from almost being padlocked shut in 1997 to being awarded IMBA Silver status in 2018. It’s more than a story of history. It’s a story of the sort of creative problem solving citizens anywhere can do to get their public land access needs met.

Carvins Cove was opened to recreation shortly after reaching full pond in 1948. Because the city wanted to protect the reservoir and drinking water supply, recreation at the Cove was limited to fishing, boating with small outboard engines and picnicking. By the 1980’s there were no trails at the Cove except for a few debris choked, eroded ones left from the CCC era, no Cove maps, only one parking lot and poor signage. The Cove’s meager recreation was managed by the city’s Utilities Department and, as one Utilities employee told me, “We aren’t trained in recreation, we don’t get paid to manage recreation so we don’t care about recreation.”

By the early 1980’s the meager amount of fishing, boating and picnicking at Carvins Cove had pretty much disappeared and a small but growing community of local mountain bikers and equestrian trail riders had the Cove pretty much to themselves.

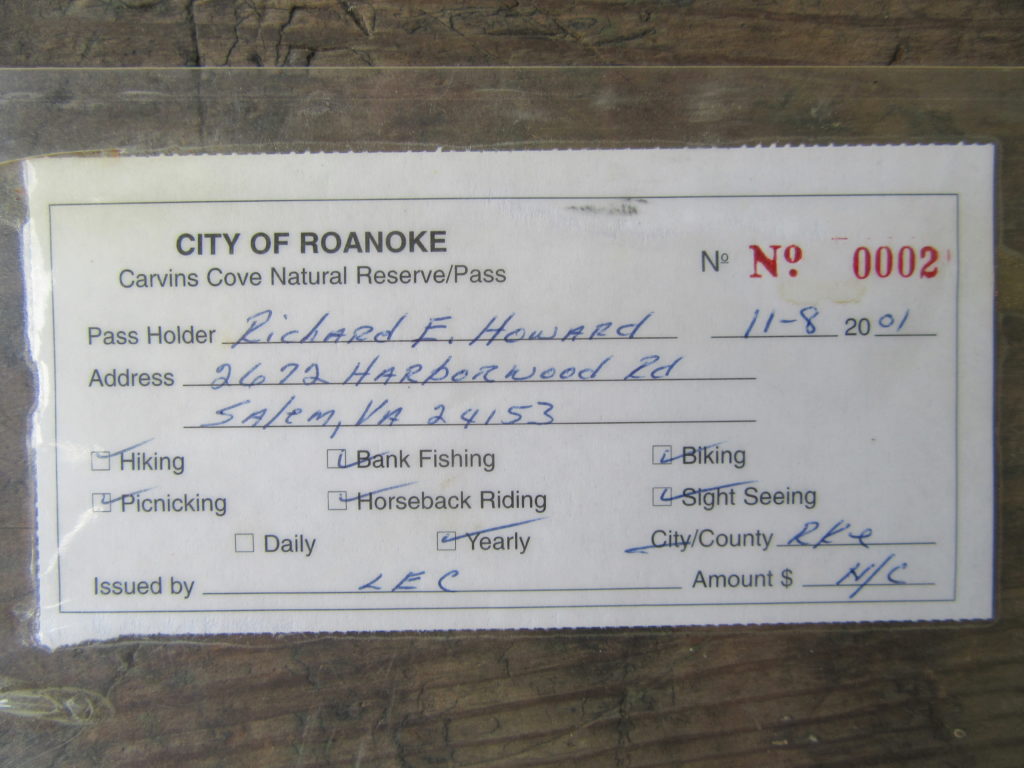

the second Cove pass – allowing him to be the second person to legally

ride a mountain bike there

I had been fishing and hanging out at Carvins Cove since I was a kid. In the 1960’s I drank beer and smoked Winstons there. In 1978 I had moved on to mountain biking and rode my first mountain bike at the Cove in 1978. In the mid 1980’s a small number of mountain bikers began to ride there and their relationship with Cove security was so low key, that in 1986 I was able to promote a small mountain bike race at the Cove without bothering to ask permission. In the late 1980’s and 90’s a few mountain bikers and equestrians performed some unauthorized trail clearing at the Cove The relationship with the Cove security people was so casual that I once received a friendly wave from one who was wearing a 9 mm. pistol as I was loading my bob trailer for a day of “outlaw” trail work. No one cared, no one asked and we got along well.

The source of the laisse-faire recreation management at the Cove was the City of Roanoke’s longtime Director of Utilities, Kit Kiser. Mr. Kiser, who could be described both affectionally and unaffectionally as “crusty” was highly regarded in the City for his tough and very efficient management of the city’s water and sewage systems. He was, after the City Manager, the most influential employee in City Hall. Kit Kiser ran the Utilities Department well but his management of recreation at the Cove was, at best, one of benign neglect and disinterest. Mr. Kiser was aware that mountain bikers and equestrians had a growing interest in the Cove and that other recreation there had just about disappeared. He had an idea about how to “manage” the Cove with the least amount of his Utilities Department manpower. He wanted to lock the 12,600 acre Carvins Cove shut.

In 1997 when I learned about the landslide at the Cove I thought that it should be an easy fix. I approached the Assistant City Manager Jim Ritchie with what I thought was a simple volunteer plan. I had known Jim socially for about ten years and he was a member of the local road bike community. What he told me was shocking. Not only would the City of Roanoke not let volunteers do trail work at the Cove, there was a good chance, if Mr. Kiser had his way that the Cove could be made off limits to all recreation. Jim said that the thinking in City Hall was split between those who wanted to continue the very outdated recreational opportunities at the Cove and an even more restrictive group led by Mr. Kiser who wanted to close the Cove to recreation all together.

As a mountain biker this was a huge red flag to me. I was sure that something had to be done to prevent the Cove from being closed but I wasn’t sure what.

The mountain bike community in Roanoke at that time was very fragmented and often oppositional to authority figures as well as to each other. Mountain biking was a new and sometimes awkwardly evolving activity in 1997 and in Roanoke it was struggling to establish a legitimate recreational and sporting identity within the community at large. The local bike shops were not willing or not able to provide anything more than sympathy for my requests for help. The Roanoke Valley’s road bike club was not willing to get involved in what it saw as “politics”. I was pretty sure that if I approached city management and identified myself as a Cove mountain biker that I would be given a polite “Thank you” and eased toward the door. My personal advocacy work to keep the Cove from being locked down was at an apparent dead end.

Like in the movies the cavalry or in this case the equestrians, came to the rescue. I hoped that the local equestrian and trail riding community might be able to provide some support so I started putting flyers up in tack shops. One of the shop owners told me to contact Carol Whiteside, president of the Roanoke Valley Horsemen’s Association. Carol had grown up near the Cove and had a maternal interest in protecting Carvins Cove. The RVHA had much influence in the Roanoke Valley. Their annual horse show was one of the biggest and best in the nation and it had a significant annual economic impact on the area. Most importantly, some of the equestrians were on a social or business first name basis with influential people in City Hall. They had credibility in the Roanoke community that mountain bikers did not have. Carol networked within the club and put me in touch with RVHA members Lowell Gobble and Frank Farmer and they took the reins, pun intended, and started lobbying their friends in the Roanoke’s City Hall.

About this time I had an eureka moment when I researched the City Code on Carvins Cove and saw that it had been written in 1956 and not updated to allow mountain biking, equestrian trail riding, hiking or trail running. I thought that perhaps Lowell, Frank and I could use the outdated Cove recreational rules to our lobbying advantage. We explained to City Councilmen that most of the recreational activities then going on at the Cove was technically illegal per the 1956 code and asked that Council update the code to make the current activities legal, and hey, while you’re at it, how about considering making Carvins Cove more accommodating to light, low impact recreation? Why not make Carvin Cove a recreational destination while simultaneously continuing to supply the city of Roanoke with a safe, reliable supply of drinking water?

I networked with six other localities in Virginia that were safely supplying both drinking water and recreation from the same land and passed that information on to Roanoke City Councilmen. Frank, Lowell and I encouraged the Councilmen to make some calls to find out how other localities made the dual usage work. I met with five Roanoke City Councilmen and gave all of them detailed proposals for improvement of light recreation at the Cove. Frank and Lowell immediately understood the potential for recreation loss at the Cove and hit the ground running. They did some some gentle, good ol’ boy, lobbying and arm twisting in City Hall, something the mountain bike community was in no position to do.

At this point in 1997, Frank, Lowell and I were somewhat in the dark. We had no idea if our lobbying was going to bear fruit though Frank and Lowell were optimistic that their personal approaches as equestrians had enabled them to legitimately “get the ears” of people who were in positions to make changes at the Cove.

I was quite surprised to turn on the local TV news in late 1997 and see Mayor David Bowers proposing that City Council establish a seven member Citizens Committee to study the Cove and make recommendations for it’s future. Realistically, the Citizens Committee could recommend pad locking the Cove shut but I knew enough about light, low impact recreation and it’s benefits to be pretty confident they would not reach that conclusion. I was even more confident when I saw the make-up of the committee. Among the seven were two well respected, local mountain bikers, Wes Best and Ian Webb. Rupert Cutler who was the retired director of the Western Virginia Land Trust became the de facto leader of the committee. Mr. Cutler was well known in City Hall for his outstanding conservation credentials. Most importantly, Mr. Cutler had a reputation as a friend of light recreation.

My friend Carol Whiteside attended all of the Citizens Committee meetings. After four or five meetings Carol reported back to me that Mr. Cutler had emerged as a strong and knowledgeable leader of the committee and he seemed to be guiding the committee toward an acceptance of mountain biking and equestrian trail riding at the Cove of the future. This was a huge hurdle for the two groups taking into consideration that only a year or so earlier we were both afraid of being shut out. Nothing was official yet but I thought we could breathe a sigh of relief.

In addition to the Citizens Committee, the city hired an independent consultant to do a study of the Cove and held several public workshops where citizens were allowed to provide input as to their visions of what the Cove should look like in the future. Two very important elements of the Citizens Committee’s and consultant’s recommendations were that the Cove be placed under a conservation easement and that the Cove be co-managed by the Utilities Department and the Roanoke Department of Parks and Recreation.

Between 1998 and 2004 several things happened that had positive impacts on the long term recreation at the Cove. Roanoke hired a new City Manager, Darlene Burcham, who was aware of the positive economic impact that enhanced Cove recreation would bring to the Roanoke Valley. She also understood that well managed recreation at the Cove would enhance the quality of life of Roanoke Valley residents.

Many Roanoke civic and political leaders had for years suffered from “Asheville envy”. That is, they wanted their city to be a tourist destination like their successful neighbor in North Carolina. But no one had an idea how to make that happen. Two City Councilman, David Bowers and Nelson Harris, looked at Carvins Cove and saw significant recreational potential there. They understood the importance of having a well-managed and marketed Carvins Cove. They also had the vision to imagine a Cavins Cove with a vast multi-use trail system connecting with the Roanoke Valley’s growing Greenway system of paved urban and suburban trails. Bowers and Harris also understood that the recreational professionals in the city’s Parks and Recreation Department would be better able to enhance and manage light recreation at the Cove than the Department of Utilities. Bowers and Harris became the forward thinking Cove advocate leaders on Council. As a result, Carvins Cove steadily evolved over twenty years to be an East Coast mountain biking destination. Harris and Bowers knew we could not duplicate Asheville but that we should carve out a distinctive recreational identity of our own. Carvins Cove became the center piece of Roanoke’s recreational identity.

A severe drought hit the region in 2001-2002 and Roanoke Valley political and government leaders realized that a regional water plan was needed. The Cove became a part of the Western Virginia Water Authority, a large regional water management system. It became co-managed by the city’s Parks and Recreation Department along with the Western Virginia Water Authority. Taking the city Utilities Dept. out of the Cove’s management loop was a big, forward thinking step for regional recreation.

The trickle down benefit of having the WVWA on board at the Cove is that they provided a second level of protection and over-sight over any possible inappropriate development at Carvins Cove for years to come.

The City of Roanoke placed Carvins Cove under a Blue Ridge Land Conservancy easement, thus ensuring that the park would be forever protected from commercial development and limiting all recreation to very low impact varieties. That was an important third level of protection.

In the Fall of 2019 the Cove will finally be physically connected to the Roanoke Valley Greenway trail system via the Hinchee Trail at Hanging Rock, only seconds from Interstate 81 and minutes by the Greenway from one of the Valley’s best breweries.

Volunteers are currently building and maintaining the Cove’s trails. Brian Batteiger has more than 3000 volunteer trail building hours. The Wednesday Crew has been building and maintaining trails for almost twenty years. Blue Ridge Gravity has built some sweet berms, jumps and table tops on a few trails. Renee Powers of the City of Roanoke’s Park and Recreation Department regularly leads trail work days at the Cove.

The future looks good for Carvins Cove. The water’s still good and there’s plenty of it. An Ironman Triathlon is planned for 2020. There are a couple of mountain bike and trail running races held every year. Roanoke is expecting that the IMBA Silver-Level Ride Center award will produce significant tourist dollars. Local bike shops will benefit from more mountain bikers at the Cove. We are “America’s East Coast Capital of Mountain Biking” and that’s quite a leap forward from the threat of padlocks, a chain link fence and “No Trespassing” signs twenty years ago.

Dick Howard 28 June 2019

Photo by: RainCrow

https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/