Are you a frustrated cubicle dweller who longs for an outdoor career?

Do you daydream of spending your days gazing at wide open spaces instead of the giant, NSA-level copier 10 feet from your desk? Below, meet 10 people who rejected the soul-sucking corporate grind and work—and play—outside for a living. But even for them, fantasy often gives way to a less glamorous reality. Could one of these careers be tailor-made for you? Weigh the pros and cons of these top 10 best outdoor jobs and decide for yourself.

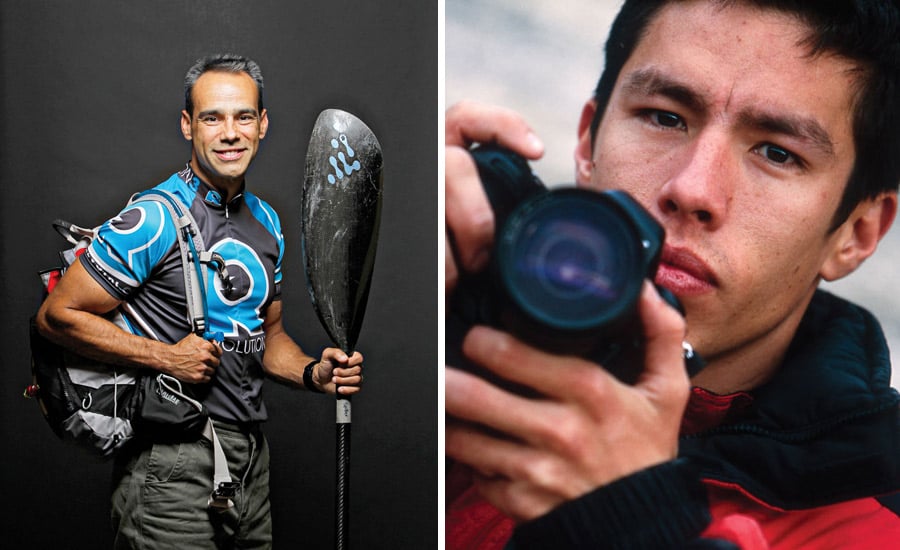

Andrew Kornylak – Photographer

- Job: Freelance outdoor photographer

- Salary range: Typically zero to mid-five figures. Six figures is rare, but possible

- Best part: Making images that will last forever and inspire countless people

- Worst part: Endless editing, paperwork, and gear sorting

- Minimum Training: Excellent photography skills; film school is a plus but not required

As the owner of his own production company (North Carolina-based Fourmile Media), Andrew Kornylak does what many people only dream about: he gets paid to take photos, make documentary films, and shoot commercial videos that feature climbing, trail running, and a host of other outdoor sports. His clients range from big-name equipment manufacturers like The North Face and Black Diamond to media giants like the Wall Street Journal and Businessweek.

“A lot of this stuff is sort of a hybrid between storytelling and commercial advertising,” he says. “Everything I do, even if it’s just a traditional documentary, is usually informed by the outdoor world, the environment, or outdoor sports.”

For Kornylak, the job fulfills a deep need to be outside as much as possible while still making a decent living and maintaining a manageable schedule. “To be on the road climbing all the time or be in the mountains or whatever, it’s kind of all-consuming if you want to do it at a high level,” he says. “The only substitute for that is something you can be equally passionate about and be completely obsessed with. For me, photography is one of those things.”

But here’s the downside: you still have to run a business with all of its attendant mundane chores. And be prepared to starve for a while while you’re at it, because starting a new company—any new company—is notoriously difficult. “The reality isn’t quite as glamorous as you think, but the payoff is real,” Kornylak said.

Robin Bible – Firefighter

- Job: Former wildland firefighter

- Salary range: $8 – 40 dollars/hour, depending on experience

- Best part: Saving lives and seeing beautiful parts of the country

- Worst part: Long hours, high stress, and extremely difficult working conditions

- Minimum Training: About 40 hours of instruction followed by plenty of on-the-job training

When the stress of your job gets you down, think of Robin Bible. As a 30-year wildland firefighting veteran (now a safety and training officer for the Tennessee Division of Forestry), he was the last line of defense between 30-foot walls of flames and the hapless civilians and countless buildings they threatened to incinerate.

If this kind of work sounds intriguing and you have a seriously high pain threshold, expect about 40 hours of introductory classroom training on topics like fire behavior and tools of the trade. Trainees also must take a “work capacity test,” part of which involves walking 45 minutes with a 45-pound pack. “The physical ability you need initially is way up there, and it just grows as you move to the next level,” Bible says. A new recruit usually starts out as a grunt on a large crew and eventually can get promoted to crew manager. Topping the ladder are incident commanders who direct battles against large fires like those that scour public lands around the country every summer.

It bears repeating: The work is strenuous in every sense of the word. 14-day details are typical, with just a day of respite on either side. That requires not only an uncommon level of physical and mental stamina, but also a willingness to be a superlative team player and watch your colleagues’ backs as if their lives depended on it—because they do. On the other hand, the thrill and sense of fulfillment are off the charts.

Tanya Hapgood – Rafting Guide

- Job: Rafting guide

- Salary range: $35-$100 per trip, depending on experience and the particular outfitter

- Best part: Variety, running rivers every day

- Worst part: Long days and lots of physical labor, especially in the summer

- Minimum Training: CPR and first aid, otherwise mostly on the job

If nothing gets you stoked quite like the roar of whitewater crashing through a rapid on a remote river, then a career as a raft guide could be your calling. Tanya Hapgood, a guide for River & Trail Outfitters in West Virginia, gets paid to ride the aquatic roller coasters offered up by nearby rivers draining the Appalachian Mountains.

Although potential rafting guides for River & Trail don’t need extensive prior rafting experience, CPR and first aid training are mandatory, as are excellent people skills. “During the interviews, we try to make sure applicants are good with people, they’re not shy, don’t anger easily, and know really corny jokes,” Hargood said.

The work also involves lots of early mornings on the river prepping gear, planning logistics, and performing all the other mundane tasks needed for a well-run river trip—not to mention sweaty physical labor during the summer. And then there are the less-than-cooperative clients. “You get people who aren’t exactly gung-ho paddlers, and people who don’t even want to get wet, which is weird,” she says. “At first, it can be a little overwhelming. But you know that’s going to be part of your day, so you get over it.”

On the plus side, this job is the antithesis of the corporate treadmill. “You spend every day outside, and every day is different,” Hapgood says. “You get to paddle class II-IV whitewater and meet lots of interesting people at the same time.”

Hartwell Carson – River Keeper

- Job: River keeper

- Salary: Not enough to make a living unless you work for a large organization

- Best Part: Spending your days paddling beautiful rivers

- Worst Part: Confronting polluters

- Minimum Training: No formal training required

Hartwell Carson is a “river keeper” who scouts for polluters on the French Broad River in North Carolina. “My primary job is to be the eyes and ears of the river and be a watchdog for pollution problems, and to use whatever tools we have in the toolbox to address them,” he said. That means paddling and collecting water samples, as well as hiking and driving nearby to look for new sources of pollution, illegal roads, and other problems. He then talks with offenders about possible solutions, and colleagues take them to court if they refuse to cooperate. Carson has been involved in other projects, too, like building a paddling trail on the river. And then there’s more mundane work like grant writing and event planning.

No formal training is required, although it’s helpful to have a background in recreation and resource management. One thing you definitely need is passion for the work, because you spend your days fighting large polluters with massive budgets who are not eager to cooperate. “If everyone would just do the right thing, there wouldn’t be a need for my job,” he says. “But at the same time, there’s often an obvious solution to a problem, and you’re stuck trying to figure out what can be done.” But for Carson, the reward is worth the hassles. “There are days where I’m paddling down a river taking samples, and it’s a beautiful day, and it’s like, I can’t believe I’m getting paid to do this.”

Read more about what Hartwell is doing on the French Broad River Trail here.

Dan Miller – Wilderness Instructor

- Job: Outward Bound wilderness instructor

- Salary Range: $65-$142/day on a seasonal basis, plus room and board.

- Best Part: Teaching students valuable life skills

- Worst Part: Very long days, little sleep, and difficult group dynamics

- Minimum Training: wilderness first responder and CPR certifications, plus a basic understanding of outdoors sports and wilderness survival

Dan Miller, staffing coordinator for the North Carolina Outward Bound School, is a self-described “jack of all trades.” Not only does he hire all of the school’s field instructors, but he also trains the staff and provides instruction for a few courses every year—most recently a backpacking and rock climbing camp. The courses typically last 14-22 days, with 4-7 days off in between.

Job seekers need to be certified wilderness first responders, know CPR, handle themselves comfortably in the wilderness, and have some experience with outdoor sports. They also must have a passion for teaching and working with people. On-the-job training will fill in the gaps. For example, Miller started at Outward Bound as an intern on canoeing trips and then was trained in other disciplines.

If getting paid to lead wilderness trips sounds like just about the perfect job, it’s not. “A lot of people romanticize this kind of work, and that’s pretty far from the truth,” he said. “We work hard every day, all day, and find ourselves hiking until two or three in the morning or dealing with students who aren’t always 100 percent excited to be there.” Add to that sleep deprivation, long periods away from home, and a heady dose of responsibility. “On the other hand, you’re helping make the world a better place and teaching students valuable skills and to be better human beings,” Miller says. “It’s hard work, very rewarding work, and it’s the best job I could ever imagine having.”

Mike Spiller – Race Director

- Job: Adventure race director

- Salary: $24,000 – $60,000

- Best Part: Creating challenging new courses

- Worst Part: Dealing with permits and other red tape

- Minimum Training: Lots of racing experience is a must, and a sports management degree is helpful

If you’re competitive and outdoorsy, what could be better than planning adventure races for a living? Mike Spiller, Race director for REV3 Adventure Racing Series, is a veteran of some 80 adventure races himself and knows a good course when he sees one. A typical REV3 Adventure race could involve trekking, paddle boarding, mountain biking, or any number of other activities. During the season, Spiller spends a good 50 percent of his time in the field scouting courses and interacting with the locals. In the off-season, it’s all about promotion, finding potential race venues, securing sponsors, maintaining equipment, and generally keeping the business going.

As far as training, nothing is more important than race experience and the passion it instills. A degree in sports management doesn’t hurt, along with a hefty dose of patience. “Sometimes the hoops and red tape for getting a course approved can be pretty ridiculous,” he said. For example, recently authorities required a bomb-sniffing dog at the finish line for a race with just 125 contestants—no doubt in response to the Boston Marathon bombing, but still.

And don’t expect to get rich for all your trouble. “The job isn’t high-paying, but it’s fulfilling, he says. “This isn’t something you do for the money.” Instead, the reward comes from designing awesome races that can tax gifted athletes or entertain families out for a bonding experience. “It’s about taking the natural surroundings and creating some sort of course, and making it fun and challenging.”

Diane Kearns – Climbing Instuctor

- Job: Rock climbing instructor

- Salary: about $85 – $125/day, depending on location and experience

- Best Part: Introducing people to what can be a life-changing experience

- Worst Part: Having to accurately assess risk for clients

- Minimum Training: Wilderness first responder and single-pitch climbing instructor certifications

Diane Kearns was bitten by the climbing bug more than two decades ago when she took up the sport of mountaineering. After tackling major peaks in the United States, Nepal, and elsewhere, she and her husband, Arthur, opened the Seneca Rocks Climbing School in West Virginia. “I love introducing people to something that turns out to be life-changing for them, helping them ease into a world where they never thought they would be,” Diane said.

Novices in particular have a lot to learn before spending all day on the rock, including equipment, safety, and basic climbing concepts. Nevertheless, you have to be sensitive and can’t go overboard. “The first time you get almost anyone hanging off a rope above the ground, they’re going to be nervous,” she says. “But you need to assess them and tailor what you’re saying and doing so you don’t put them in the freak-out zone.” That means being an excellent teacher who can assess each student’s physical skills, mental capacity, and emotional state.

If there’s one thing Diane doesn’t like, it’s the incredible responsibility she faces. After all, students entrust her with their lives. “I wish you could do this without taking on the risk for someone else, but that’s part of it, so you take it on and mitigate it,” she says. “At the same time, you want clients to have a blast. It’s a little bit of assessment, a little bit of teaching, and a lot of just having fun.”

Paul Super – Biologist

- Job: Biologist/research coordinator

- Salary Range: $15 – $40/hour, depending on experience; more for upper management

- Best Part: Working with scientists who study all kinds of fascinating subjects

- Worst Part: Lots of paperwork

- Minimum Training: Master’s degree in the appropriate discipline; volunteer or work-study experience helps

For outdoorsy people with a scientific bent, few gigs are better than working as a scientist at a national park. Paul Super is a biologist for Appalachian Highlands Client Learning Center in Great Smoky Mountains National Park, where he oversees the research program there. A big part of his job is to bring new scientists into the park to work on conservation issues. “We try to understand what we’re protecting and how best to protect it,” he says. He also works with volunteer non-scientists to collect and analyze various types of environmental data. All of this puts him in the field two or three times every week.

If you want a job like this, formal education is a must. Super, who has held his position for 12 years, holds a B.S. in natural resources and an M.S. in ecology. The good news is there are often plenty of opportunities to try other positions with less rigorous requirements, see what fits, and go from there. “A national park has many different jobs,” he says. “In small parks, you have to do just about everything. In larger parks like this, you get to specialize.”

Super’s favorite part of his job is learning from people who work in a variety of fields. “I get to collaborate with scientists who study all sorts of fascinating things, from how rain falls in the mountains to how obscure organisms live, and then I get to share what I’ve learned with lots of different people.”

Gene Hamilton – MTB Coach

- Job: Mountain biking coach

- Salary: $100 – $250/day plus travel expenses

- Best Part: Seeing clients improve and learn to love the sport

- Worst Part: Travel between camps, business chores

- Minimum Training: Excellent teaching and solid mountain biking skills

Gene Hamilton, owner of Arizona-based BetterRide, holds mountain biking camps all over the mid-Atlantic. Although that means lots of travel, it also affords plenty of opportunities to do what he truly loves: teaching. “I like seeing people grow, and I often get excited e-mails—sometimes years later—about how much better they got,” he says. “And I really love it when people tell me the camp improved their life, not just their mountain biking.”

Camps usually consist of three-day seminars starting with plenty of theory that eventually is put into practice, although not as soon as some clients might like. “A lot of people have really high expectations and want to do something new in half an hour,” he says. “You really can’t learn a whole lot even in a two- or three-hour lesson.” Eventually they hit the trails, which get steadily harder as the camp progresses. “It’s a very intense program,” he says, including wheelies, cornering, breaking, negotiating switchbacks, trail reading, and other maneuvers.

Potential coaches must be excellent teachers and have above-average mountain biking skills. Humility is also mandatory. “You have to enjoy people and have a very small ego, because it’s not about you—it’s about getting other people to do things,” Hamilton says.

Alex Bradley – Ski Patroller

- Job: Ski patroller

- Salary: $10 – $15/hour, depending on experience and medical training

- Best Part: Skiing every day before the crowds

- Worst Part: Dealing with ill-behaved patrons

- Minimum Training: EMT certification and solid skiing ability

For 17 years, Alex Bradley has lived his dream job: getting paid to carve fresh powder when no one else is around. That’s because being a ski patroller is more than just getting people out of trouble; much of the work involves checking trail conditions, making sure the lifts are operating, fixing errant trail signs, sweeping for stragglers, and generally taking care of things before the mountain opens and after it closes. “Other than that, you’re just skiing around and doing public relations, making sure people are behaving and not getting in over their heads,” he said. On a good day, no one gets hurt. But if someone does, it’s Bradley’s and the other patrollers’ job to get the victim stabilized and down the mountain to an ambulance.

At Bradley’s resort, Stowe Mountain in Vermont, every ski patroller holds an EMT certification and is a “confident” skier, although not necessarily an expert. “You’re probably going to get better once you start training with us,” he said.

The worst part of the job is dealing with people who refuse to follow the rules. “I don’t like to be the bad guy,” Bradley says. But he forgets all that when he’s gliding down a black diamond with no one else in sight. “I love the first runs of the day, opening the trails, especially on a very good ski day. It’s really nice because you’re the only one out there, it’s quiet, and the skiing is great. That’s what brought me to this job.”