Photo credit: Sarah Vogel

Part 8: Ecotherapy for You

The Nitty Gritty

So far in this series, I have talked about the benefits of nature connection and why it heals and enriches our lives. Perhaps, I hope, I’ve convinced you of the power of nature in healing and well-being, in helping us remember to play, in helping understand ourselves, and in helping us remember that a world also exists outside ourselves. I’ve thrown statistics and science at you, but at the end of the day, it’s all words on a screen. And if that is the only thing I leave you with, I’m afraid all I’ve done is kept you in front of that screen rather than in the real world, where all the magic happens.

The big question remains: What can you do about it?

First, let’s explore the most popular forms of ecotherapy. No one size fits all — we all have different lives, different commitments, and depending on where we live, different access to the natural world. But nature is all around us and I believe there is something for everyone. Note that many of these forms of therapy are available with the assistance of a professional, but can also be done independently.

- Horticultural: This therapy uses plants and gardening, usually done in community gardens and greenhouses. Maintaining indoor plants can be similarly healing, if access to a community garden or outdoor space is not available. This type of therapy can be very helpful for the elderly, improving memory, mobility, and socialization.

- Animal-assisted: Interacting with animals is proven to reduce stress and improve well-being. Equine-assisted therapy is a more formal style that can be very effective in treating children with autism. If you have a pet, consider carving time out of your day to bond with your fur-baby, teach them some tricks, take them for a walk, or just give them an attentive snuggle.

- Green exercise: Exercise done outdoors is good for the body and mind, and the extra Vitamin D doesn’t hurt either. You can go for a walk, run, cycle, or do yoga in the park. Even doing yard work can feel great after a sweaty day of mowing the lawn or raking leaves. Parks in every city need volunteers to help maintain trails, fix fencing, and otherwise beautify the natural landscape. The bonus of volunteering, of course, is that you feel great about helping the community.

- Nature arts and crafts: Making art in nature is a great activity for people of all ages, but may be particularly engaging for parents and children. You can stack cairns, make a natural Mandala, create a rock garden, make wind chimes out of sea shells, or paint with juice from berries and red clay. Nature photography can be another great way to notice the little things, like rock textures and bark, soft lighting in sunrise and sunset, or the the ripples when a fish strikes at a water strider.

- Adventure therapy: Adventure therapy should always be undertaken with the guidance of professionals, as it comes with greater risks than the options listed above. Adventure therapy involves participation in different challenging activities such as caving, rock-climbing, ropes courses, white-water rafting, or strenuous hikes and camping excursions. Often used to treat people suffering from addiction, adventure therapy is a way for people to challenge themselves in new ways, improving self-concept, self-esteem, problem-solving skills and empowerment.

- Wilderness therapy: Wilderness therapy is similar to adventure therapy, but typically lasts longer (approximately six to ten weeks). Traditionally used for teenagers and young adults, this form of therapy challenges participants to use coping skills, communication, cooperation, and self-reliance to survive in the wilderness. Like adventure therapy, it is vitally important to find a reputable organization due to the dangers of wilderness survival and the sensitive nature of working with minors. Wilderness therapy should always be overseen by licensed mental health professionals with special wilderness training to ensure safety. Make sure to look for programs accredited by the Outdoor Behavioral Health Council for high quality care.

- Nature meditation: Meditating in a natural setting can improve mindfulness and reduce stress. Sounds of flowing water, birdsong and insect chatter, the smell of pavement after a heavy rain, the feeling of cool dirt under your bare feet, the sight of a sky full of stars — they are visceral reminders of our part in the circle of life. It can be calming, enlightening, and humbling.

Like with forming any new health regimen, the best activities are the ones you are most likely to continue doing. Some people will love gardening, but others may prefer the adrenaline rush of rock-climbing. If you’re a gym rat, outdoor exercise may be a simple transition to a routine you’ve already established. If you love yoga and meditation, you could try moving it outside or to a place with access to window views of nature. If you already walk your dog everyday, consider making the trip to a park with tree canopy or a body of water. Options are limitless, but give careful thought to which activity you’re most likely to maintain. Nature disconnection is a part of today’s culture, which means that habits may be hard to form. Make it easier on yourself by doing something you love.

With such busy lives, another important question to answer is: How much is enough? More is better, but scientific research has determined that 120 minutes per week of nature exposure is the threshold at which people report feeling improvements in health and well-being. This could be a two-hour hike on the weekend, or 20 minutes per day of sitting in the park. Quality does matter — spending time by the beach or on top of a mountain can have more profound effects, but sitting in an urban park is far better than sitting in front of Netflix. For people who want a full mental reboot, evidence suggests our cognitive abilities improve significantly after three days in the wilderness.

Although nature connection itself carries little risk of harm, nature can indeed be dangerous. Please be sure to understand and prepare for the risks before venturing into the wild. Furthermore, it is important to note that the field of ecotherapy is still relatively new, and not regulated by the American Psychological Association. Ecotherapists can gain training and certification through organizations such as the Earthbody Institute and other reputable organizations. Do not be afraid to ask ecotherapists about their qualifications and experience in order to get the highest quality of care. Finally, remember that ecotherapy is not a replacement for medical or mental health treatment by licensed professionals, but rather a supplement to a complete, holistic approach to well-being.

A Tree Doesn’t Stand Alone

As we become an increasingly urban society, it’s important to ask: Where can we find green spaces and how can we protect them? As it turns out, ecotherapy may be the answer not only to our individual well-being, but also to well-being of our communities and our planet.

In my quest to find local green spaces, I reached out to Professor Emeritus of Landscape Architecture Reuben Rainey at the University of Virginia. Professor Rainey has dedicated much of his career to understanding how different environments can heal individuals and the community as a whole.

“Nature is not a frill,” Professor Rainey told me more than once. “It’s good medicine, and it’s one of the keys of dealing with urban issues. I’m not particularly upset that were are turning into an urban civilization because it could have great benefits as long as we design our cities so that we flourish.”

Although Professor Rainey has researched extensively about the design of hospitals to heal medical patients, he is particularly interested in salutogenic health, an approach that focuses not solely on the factors that cause disease, but also on the factors that generate well-being. “We are trying to create flourishing. If you design a place with a garden, for example, people will gravitate to that place, promoting socialization, exercise, and exposure to nature. We can design streetscapes with tree canopies. We can encourage building parks. Neighborhood parks, community parks, larger trail systems — these all contribute to a healthy community.”

Photo credit: Sarah Vogel

Professor Rainey has seen success in retro-fitting industrialized cities to promote green space: the Atlanta BeltLine (formerly a railroad corridor), Seattle’s Gas Works Park (formerly a gasification plant), New York’s Brooklyn Bridge Park (formerly shipping docks) and High Line Park (formerly the NY Central Railroad). In Richmond, one of my favorite parks is the James River Park Pipeline Walkway, a riverfront trail along the pipes below the railroad. “You can reclaim major industrial areas,” explained Professor Rainey. “Extinct infrastructure can be transformed into green infrastructure.”

The impacts of these kinds of city improvements are profound, and go far beyond aesthetics. “For example, controlling for variables like ethnic background and economic status, a city with greater tree canopy has a considerable reduction in crime rate,” said Professor Rainey. Unfortunately, he explained, people don’t know about these studies and don’t recognize their importance. “In medical facilities one of the first things to go in a budget cut is the garden.”

“But don’t they see the long-term payoff?” I asked in frustration.

“Well, you just put your finger on it,” he replied. “In this culture, it’s very difficult to measure long-term benefits. Some people think it’s in our DNA as creatures. We have a hard time thinking beyond today, beyond the saber-tooth tiger that’s going to take a nibble out of us. The cost of some of these interventions could be recouped in two or three years, but you’re going to have a hard time getting people to see that.”

I asked Professor Rainey what we as individuals could to do protect and promote green spaces in our own communities, but was met with a disheartening answer: “The problem is always financial. Changes are not being done by the state or city, but by private-government partnerships. And that’s the way it’s going to be done.”

But, he assured me, that’s doesn’t leave us powerless. “As a nation, we are good at forming interest groups. Two impressive examples of private-public partnerships are the restoration of New York’s Central Park and the creation of the new Brooklyn Bridge Park. Citizens coming together can make a big difference.”

Professor Rainey has seen these kinds of changes in Charlottesville since he moved to the city in the 1970s. Ivy Creek Natural Area was founded thanks to the efforts of a lone kayaker, Babs Conant, who saw a strip of red surveyor tape along the shoreline of the Rivanna Reservoir and jumped into action. Conant rallied other citizens to enlist the help of The Nature Conservancy to transform the former farmland into a protected reserve. And in 2018, with the efforts of volunteers and envrio-activists, the city of Charlottesville signed off on the construction of an 8-acre botanical garden at McIntire Park.

“I’m an optimist,” said Professor Rainey. “Even the most modest thing can build into something bigger.”

—

Professor Rainey is not alone in the belief that we can make a difference. I made my way back across the mountain to Harrisonburg to meet with Jan Sievers Mahon, Director of the Edith J. Carrier Arboretum where I walked through the labyrinth in my exercise with ecotherapist Pat Cheeks.

Photo credit: Sarah Vogel

Mahon and I strolled through the grounds, watching ducklings trail behind their mothers in the pond, listening to kids shrieking in delight in the nature family garden. Located on the grounds of James Madison University, the EJC Arboretum is the only arboretum on the campus of a Virginia state university, its 125 acres of mature Oak-Hickory forest home to hundreds of native plant species. JMU students often visit the arboretum for quiet solace or research, but the sanctuary remains open to the community and visitors year-round, dawn to dusk.

“The Arboretum serves as a bridge to the community,” said Mahon. “Here people have a way to get away from their busy lives and connect with the natural world. You don’t need to drive hours to be out in nature when it’s right in the middle of the city.”

Photo courtesy of EJC

Harrisonburg, a sprawling town stretching across the Shenandoah Valley, has expanded substantially over the years. But the EJC Arboretum has remained a peaceful, green haven for residents and out-of-town visitors to get away. For children, they offer story time in the understory of the forest, soil and water workshops, educational tours, art classes, planting ceremonies, bug hunts, and summer camp. Adults can enjoy sound bathing, forest bathing, outdoor yoga, tai chi, birding workshops, wildflower walks, butterfly tagging, and more.

“It’s important to remember that nature is all around us,” said Mahon. “There are parks and trails everywhere in this region of the state, and abundant opportunities to get back in touch with the natural world.”

As we walked the footpaths under the arboretum’s lush canopy, Mahon occasionally stooped to the forest floor, identifying plants in bloom. She squatted and caressed the speckled green leaf of a toadshade trillium, noting the recently budded wine-red flower at its center. “By the way, have you heard of fungal mycelium?” she asked, looking up at me.

I’d seen it before in search of firewood after turning over logs and large branches — pale, web-like networks of white fungus, spreading beneath the dark peat of the forest. It is the root system of mushrooms but plays a much larger part of our woodland ecosystems. Like an underground internet or ‘wood-wide web,’ as others have dubbed it, it connects hundreds of trees in a single ecosystem, helping them communicate and share resources.

For plants that are unable to gain enough sunlight beneath a thick forest canopy, excess nutrients from a large tree can be transferred through this underground network to help the survival of smaller seedlings. Mycelium will also transmit nitrogen and phosphorus from dying plants to healthy neighbors, and send warning to nearby trees of attacks from insects or pathogens. It is not yet fully understood by science, but has challenged the meaning of intelligence in living species and plant life.

“So science is beginning to realize that a tree doesn’t stand alone,” said Mahon. “The forest acts together as a single organism — trees communicate with each other, sending nutrients, water, and information to one another. Where one individual begins and ends becomes increasingly impossible to untangle. This interdependence is helping the whole to be stronger. Nature has figured it out. If we would go to nature to ask for guidance, we might realize how connected we as human beings also are.”

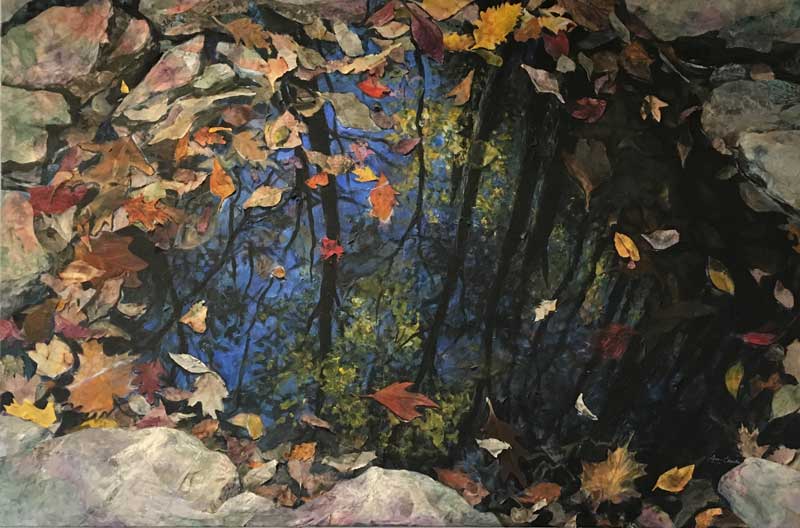

Courtesy of Ann Cheeks

At that point, I was struck by how many connections I had noticed during my research for this article. Some people already knew each other through the mental health field and academic circles, but many other connections were unknown until I started putting the pieces together. Artist Ann Cheeks paints scenes from the Blue Ridge Mountains, paintings that have been used by her sister, Pat Cheeks, for ecotherapy interventions. These paintings have also made their way to the walls of UVA Hospital, selected by the Art Committee, on which Professors Dennis Proffitt and Reuben Rainey have both been long-standing members.

Years ago, Mahon watched Professor Rainey’s documentary series on PBS, Garden Story: Inspiring Spaces, Healing Places, doubtlessly impacting the operations of the EJC Arboretum. Mahon’s daughter worked at Wildrock, the natural playscape founded by Carolyn Schuyler. Schuyler is a board member of The Women’s Initiative (TWI), a counseling center in Charlottesville that offers ecotherapy workshops free of charge to the community. And counselors from TWI volunteer at the Center for Earth-Based Healing (CEBH) to facilitate ecotherapy camps.

Said Mahon, “Really, we all want the same things. We all want love, we all want to be loved, we all want to live a good life; to have control over our lives. And the truth is, beyond this human veil, we are all one as well. We just separately reflect a truth that is, underneath, shared by all.”

In my research for this article, I found a deeply interconnected web of people impacting each other in profound ways, some visible and intentional and others invisible and unforeseen. Health professionals, city planners, activists, parents, children, academics, law enforcement, legal entities, hospitals, schools — our society is its own circle of life, and one in which we all play a part. In a world so full of life dependent on each other, we never stand alone.

Pascal’s Wager

Photo credit: Sarah Vogel

I took this picture in Seoul, South Korea.

I don’t want to live in a world where they sell Hello Kitty branded pollution masks at the local pharmacy. There’s a lot wrong with that — maybe it’s just me, but using the most commercial mascot of all time to market a product that filters toxic air to children feels wrong.

There is a humbling future ahead. The choice is ours whether we humble ourselves or nature does it for us. Already, glaciers are shrinking, sea ice is melting, summer heatwaves and natural disasters are sweeping the globe, and we’re facing the worst extinction crisis since the dinosaurs got wiped off the map. People are starting to experience emotional fatigue as the impacts of climate change become increasingly evident. They’re calling it enviro-depression. And unfortunately, depression gives way to apathy — it’s just easier not to care.

I can appreciate that these are big issues, and difficult to solve. I can appreciate it doesn’t seem productive to take a walk in the park, to go fishing, or to catch butterflies with your kid. I’ve heard people grow cynical about fixing the planet. What’s the point? The actions of one person don’t matter, they say.

Maybe. But I’ve got a wager.

I’m not a philosopher, but I’m going to borrow an idea from someone who was. In the 17th century, Blaise Pascal argued that our best bet is to believe in God because if God actually exists, the nonbelievers will suffer eternal hellfire, and the faithful will be rewarded with an eternity in heaven. If you don’t buy in and you are wrong, you have everything to lose. On the flip side, if you do buy in, you have nothing to lose and everything to gain. His argument has some logical fallacies which I won’t explore here. But let’s swap God for the belief that we can make a difference — and I think his argument holds water.

Giving in to apathy ensures that nothing changes. Believing change is possible, however, at least gives us a chance.

Where I live in Nelson County, you can’t get more than a few miles down Route 151 without seeing the same big, blue sign: “No Pipeline.” As many readers likely already know, if completed, the Atlantic Coast Pipeline will send fracked gas 600 miles across two national forests, the Appalachian Trail, Shenandoah National Park, and thousands of acres of private property in three states: West Virginia, Virginia, and North Carolina. Opponents argue that the pipeline will scar the natural environment, cutting through rivers, streams, and untouched forested areas, compromising the safety of drinking water and endangering sensitive native species.

Putting aside political differences, bipartisan collectives like “All Pain, No Gain” have come together to raise awareness about the pipeline by running opposition advertisements on radio and television. Friends of Wintergreen, Friends of Nelson County, the Sierra Club, the Southern Environmental Law Center, and Appalachian Voices have also expressed opposition, citing the infeasibility of construction and the dangers to the environment and residents. Private landowners have blocked surveyors from their property, even in the face of lawsuits from Dominion Energy.

Last year, the U.S. Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals struck down two vital permits for construction, indefinitely stalling development of the pipeline. The fight isn’t over, but it’s a win. I’m proud to say the people of Appalachia haven’t taken it lying down. At the end of the day, a handful of people from rural Appalachia threw a wrench into the money-making scheme of a 65 billion dollar company. So tell me again that we can’t make a difference.

Things are starting to change.

On the first Earth Day in 1970, millions of people mobilized across America, demanding legislative changes to protect the environment. Within the next five years, the government created the Environmental Protection Agency, the Clean Air Act, the Clean Water Act, and the Safe Drinking Water Act. And that was only the beginning. In that same decade, scientists raised the alarm about our thinning ozone layer, prompting legislation to phase out certain aerosols and other chemicals responsible for the damage. In 2018, it was announced that the ozone layer was finally healing and could be repaired by 2060.

The fossil fuel industry is dying — oil and gas stocks are at their lowest since 1979, largely due to increased cost-effectiveness of renewable energy sources. Electric car-charging stations have popped up in parking lots, and in the last decade, solar power has experienced an average growth rate of 50% per year. Veganism, vegetarianism, and flexitarianism are becoming more widely accepted, with plant-based meat substitutes like Beyond Meat hitting major grocery stores this year. People are starting to get louder about protecting the environment, and politicians and investors are starting to listen.

Perhaps we need to stop looking at our personal impact in the form of numbers like kilowatt hours, pH levels, pounds of carbon emissions, or degrees Celsius. Because when we look at things that way, the impact of the individual seems insignificant. But movements aren’t built on numbers. They are built on the strength in numbers. And if nature reconnection gives us back our ability to care, I don’t see what we have to lose.

Final Thoughts

Humans have come a long way since we cropped up a few hundred thousand years ago, but one thing has always remained the same: from Clovis points to Clonazepam, we’re always searching for new solutions to our problems. Our love of tinkering took us to new heights of innovation our ancestors couldn’t have fathomed, setting us apart from the rest of the animal kingdom. But pulling ahead of the pack made us forget we are still part of it, and in our search for answers, we may have lost ourselves.

Ecotherapy is something we never knew we’d need. Not that long ago, life was ecotherapy. We were intimately connected to the earth, aware of its blessings and dangers, dependent upon the literal fruits of our labor. Now we are an urban species sequestered indoors, our food packaged neatly in plastic containers so we never need to think about where it came from. As a species, we are not well. Mental illnesses plague a huge percentage of the population, particularly with ADHD, depression, and anxiety. Maybe, rather than searching for new solutions to our problems, we should look to the oldest medicine shaman of all time: Mother Nature.

Ecotherapy may be the cure for our ailments. For some people I met on my journey, it saved their lives. Nature can remind us of our strength and adaptability, to have gratitude for the little things, that it’s okay to play, and that none of us are ever truly alone. But most importantly, it may be a cure for our collective apathy, and subsequently a cure for the planet.

It’s easy to give up — on ourselves, on others, on the world. It’s easier not to care. It’s easier to blame our problems on technology and screens and the media. Our aggressive problem-solving has come to bite us in the ass, and created an entirely new problem of its own. Perhaps we deserve this fate we’ve brought upon ourselves.

But are we so far gone that we’ve also forgotten what makes us most human?

Even as cities and populations grow larger every year, the world grows smaller. Our propensity to innovate and problem-solve has given us the ability to communicate instantly across continents, to mobilize millions with a few clickity-clacks on the keyboard. And while all this new technology may dominate our lives, it is not what defines us as a species. I believe it is much simpler than that.

Standing at the bottom, a man doesn’t just see a hill. He sees what it takes to climb it. In that brief, unconscious moment he measures himself against the world, even if no one ever asked. Time and time again, we have risen to the challenges we assign ourselves because we’ve had no choice — we were never the fastest or the strongest. And yet, we’ve summited mountains, built pyramids, dove the oceans, and sent radio signals into space. What makes us most human is not the strength of our bodies, but the strength of our spirit.

So why let it die now?

Ecotherapists and Resources in Virginia

- Pat Cheeks, private business owner of Natural Transitions

- Beverly Ingram, private business owner of Go Into Nature

- The Center for Earth Based-Healing

- The Women’s Initiative

- Wildrock

- The Edith J. Carrier Arboretum

Recommended Reading

- The Nature Fix: Why Nature Makes Us Happier, Healthier, and More Creative by Florence Williams

- Vitamin N: The Essential Guide to a Nature-Rich Life by Richard Louv

- Last Child in the Woods: Saving Our Children from Nature-Deficit Disorder by Richard Louv

- Communing with Nature: A Guidebook for Enhancing Your Relationship with the Living Earth by John L. Swanson

- Forest Bathing: How Trees Can Help You Find Health and Happiness by Dr. Qing Li