It’s thirty-five degrees outside according to the car thermometer, here where the Bartram Trail crosses the North Carolina/Georgia state line and heads north into the Overflow Wilderness Study Area. At mid-day, this is the warmest temperature I will encounter on this clear late March afternoon.

Pockets of snow still lie about the trailhead where my wife is leaving me to walk twenty-three miles over three days to Hickory Knoll Road, where she’ll pick me up, in thunderstorms according to the forecast.

I look back as she pulls away, wave, and then adjust my pack to the heavy load of winter gear. The Bartram Trail, so named for the now famous 18th century American naturalist, William Bartram, crosses the Georgia state line after originating in northeast Georgia, winding its way through the mountains for thirty miles before this point, continuing on for another seventy before terminating at the summit of Cheoah Bald and its intersection with the Appalachian Trail.

William Bartram

Bartram was on a three-year southeastern mission, funded through the generous patronage of the British doctor, John Fothergill, who paid him for the New World plant specimens he collected and the artwork he produced along with it. Bartram was a Quaker from Philadelphia, where his father John owned one of the most significant gardens in America, and who also served as King George III’s Royal Botanist.

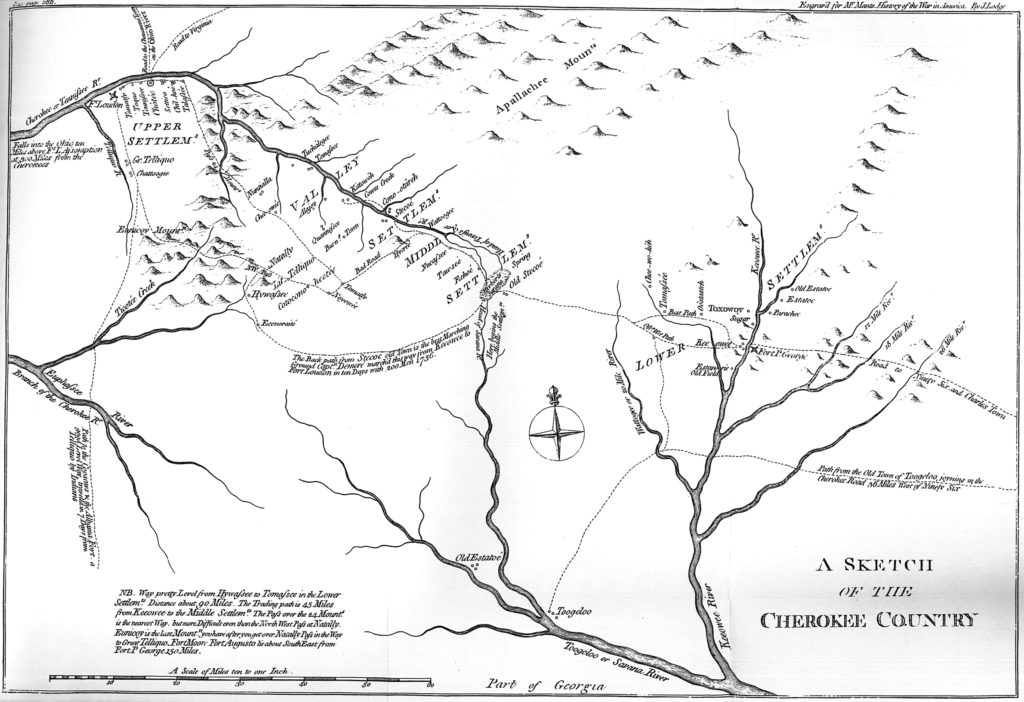

He had a way with native Americans, who trusted him and his motives. He never carried a gun, a bible, or anything to trade. He simply wanted to learn from them and gain an understanding of the plant world they inhabited. From the Upper Keowee, he pressed on into the headwaters of the Chattooga River, fording streams with his horse, occasionally swimming, and collecting, describing, and painting his encounters with the natural world along with the abandoned and burned out villages of the Cherokee.

His ultimate destination was the Overhill towns of the Cherokee, near

Near modern-day Clayton, Georgia in Rabun County, he turned north at a point known as The Dividings – a major intersection of native American trade paths – and headed into the Little Tennessee River valley, a landscape he describes as “one of the most charming mountain landscapes perhaps anywhere to be seen.” His descriptions of the mountains and valleys are rapturous and filled with eighteenth-century romantic ideas of the sublime, as well as scientific nomenclature.

Historian Roderick Nash, author of Wilderness and the American Mind, credits Bartram with being the first American to elevate the American landscape with such romantic descriptions, and the first to use the term wilderness in a way contrary to the prevailing attitudes of conquest and subjugation of all things wild and untamable.

His 1791 publication, Travels, provides the reader with the only account available of the western North Carolina mountains from that time. Without it, we would know little to nothing about the Little Tennessee valley’s 18th century natural and cultural history.

It’s little surprise that a group of Bartram enthusiasts formed the North Carolina Bartram Trail Society almost forty years ago and began designing and building a trail to honor this legacy. The architects of this incredible public resource agreed that it should not deviate more than thirty miles from Bartram’s original route.

From where I am walking today, I am close to his original path, where I traverse the upper Overflow creek drainage, headwaters of the west fork of the Chattooga River.

Upon leaving the Wilderness Study Area, the trail crosses State Highway 107 and climbs Scaly Mountain, so named for its dramatic rocky summit, and then traverses the entire length of the Fishhawk Range, almost twenty miles of fantastic ridge walking. When I reach the summit, the temperature is in the mid-twenties and the ground is frozen solid.

Stunning views of the Little Tennessee valley and the Nantahala mountain range lie before me, and I descend down to the headwaters of Tessentee creek to camp for the night. I have seen four people all day, and those were at the road crossing. The next day I see a few more at the popular Whiterock mountain, but for eight miles, that’s it.

I pitch my tent far back in rhododendron that evening, as the winds are picking up, and it’s sleeting. It’s lonely and quiet on this high spine of the ridge, and I read myself to sleep, wondering what kind of weather I’ll face tomorrow.

Over the next month, I section hike the remainder of the trail, skipping the ten mile road walk that comes after leaving the Fishhawks, which can also be done by canoe on the Little Tennessee River, an option that many who are hiking the entire trail choose, as it is officially part of the trail.

Just west of Franklin, the trail climbs the Nantahala mountains, a steep ascent of almost 4,000 feet over eleven miles to the summit of Wayah Bald. Wayah Bald is the site of one of my favorite passages from Travels, where Bartram stands upon its summit and describes “a sublimely awful scene of mountains piled upon mountains.”

Much like Bartram’s path over the Nantahalas in 1775, the trail now crosses the mountain and descends steeply into the Nantahala Gorge, where Bartram

I love this section of trail, not just for its rugged beauty and rich cove forests, but for knowing that this rare American walked either directly on this route or close to it. I spend three long days walking this section in April, munching on ramps and enjoying early spring wildflowers and the arrival of neo-tropical songbirds. This is a remote section of trail, and I see no other hikers on it, except for where it is shared with the Appalachian Trail for several miles on the ridgeline of the Nantahalas. Here it is loaded with A.T. thru-hikers, but when I leave it and descend to Nantahala Lake, there is no one else for the next seven miles. For over twenty miles and three days on this next section to Highway 19, I see no other hikers.

Then out of the Nantahala Gorge and back again to the high country – the long steep five -mile climb to the summit of Cheoah Bald, with its grassy open fields and wild roadless setting. Here the trail terminates at its intersection with the Appalachian Trail. Check it out. And before you go, make sure to pick up a copy of Bartram’s Travels, and enrich your hiking experience even more. It’s a journey you will not forget. For more information on hiking the trail, visit www.ncbartramtrail.org