Take the Cave City exit off Interstate 65 in Kentucky and drive past the life-size dinosaur replicas, the abandoned putt-putt course, and Yogi Bear’s unseasonably quiet Jellystone Park. You can also jump in a bumper boat to show your tube-maneuvering skills, but let’s face it, people only come to this quaint Kentucky town to see one thing: caves. Mammoth Cave National Park, the longest cave system in the world, just happens to be a few miles down the road.

In addition to the main attraction, the 53,000-acre park is home to nearly 200 other smaller caves and bodies of water like the Green River. But Mammoth Cave itself holds the most allure. It’s one of the few places on Earth that holds as much mystery today as it did when Native Americans set foot into the dark abyss nearly 6,000 years ago.

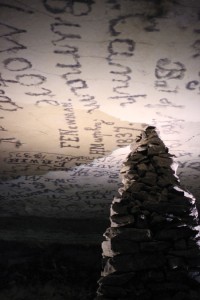

In the Beginning

Gourds, spear points, burnt cane torches, and even an Indian corpse tell us that these people visited the underground world but did not live there. Researchers believe the Native Americans collected minerals like gypsum and selenite from the cave walls for their medicinal and ceremonial value.

By the time the first European settlers came to the plateau that stretches above the cave system, tribes like the Shawnee and Cherokee had been hunting there for generations. Soon, however, those that were spared from disease and warfare were pushed from their hunting grounds to make room for a new era of cave exploits: those of the white man.

When war with England broke out in 1812, a sudden demand for black gunpowder drove men to the hills. Wealthy gentleman looking to capitalize on the war came in search of caves with saltpeter deposits, used to make gunpowder. Mammoth Cave was filled around the clock with over 70 slaves and a handful of oxen working to supply the American military. Only a year later in 1813, the cave’s owners abandoned gunpowder business for another endeavor: tourism.

Then, in 1838, a wealthy man from Glasgow, Ky., purchased the cave and brought with him a slave who would change the future of Mammoth. That slave’s name was Stephen Bishop. Although he would go on to sell the cave only a year later, Bishop would become Mammoth’s foremost explorer and guide. Bishop became the first person to push the boundaries of exploration in Mammoth when he found a crawlway that crossed The Bottomless Pit, a canyon-like section of the cave that most had assumed to be “the end.” Bishop also discovered the underground Echo and Roaring Rivers as well as the eyeless fish that reside in the cave. In all, Bishop did more than entertain and guide visitors; his explorations marked the first contributions of a true caver. He managed to discover and map roughly 25 miles of the cave, a crucial step toward understanding the vastness of this largely unexplored world, which he referred to as a “grand, gloomy, and peculiar place.”

Little did Bishop know that he and his rough sketches of Mammoth Cave would spur a frenzy of exploration in the early 20th century. Discovery stories of neighboring caves also drew attention to Mammoth’s already extensive system. One story in particular was the tragic tale of caver Floyd Collins. In 1925, the Kentucky native attracted media outlets from around the country when a 27-pound rock landed on his ankle and trapped him during a reconnaissance mission in nearby Sand Cave. Collins died in his underground entrapment, but his story would put Cave City and the surrounding caves on newspaper headlines around the globe. That same year, the Mammoth Cave National Park Association was created to begin drafting plans for turning Mammoth Cave and the surrounding land into one of three national parks in southern Appalachia.

Mammoth Becomes Mammoth

Fast forward to 1938. An eight-year-old boy from Shelby, Ohio, and his mother are visiting Mammoth Cave for the first time. The boy, who has long been fascinated with caves hidden beneath kitchen chairs and blankets, carries a flashlight he purchased with his own money. He bounces the beam of light off the cave’s solemn walls, his eyes wide, heart racing; he has been waiting for this moment to come for nearly three years.

The tour guide leads the group through Mammoth’s chambers, reciting bits of geology and history along the way. The boy, however, is lost in the moment, the grandeur and mystery of the cave sending his mind into a feverish wave of unanswered questions and stories of lost souls in hidden passageways.

“Where does that go?” the boy finally asks, pointing the beam of light at what appears to be another passage. The tour guide stops and chuckles, apparently amused by the boy’s inquiry.

“Why, it doesn’t go anywhere!” the guide says, which causes the group to erupt in laughter.

The boy, rightfully confused, keeps his thoughts to himself for the remainder of the tour, but his incessant curiosity stays with him long after leaving the cave. That boy would grow up to be one of the most influential cavers in the development of Mammoth Cave. His name is Roger Brucker.

Although Brucker dabbled in some “very small and very muddy” Buckeye caves after that first exposure, it would be another 16 years before he returned to the Mammoth Cave region. In 1954, the National Speleological Society (NSS) chose Brucker to join 64 cavers on a sponsored weeklong expedition to Crystal Cave, a trip that would alter the futures of both the cave and Brucker himself.

“All of a sudden caving turned from a hobby to an obsession,” Brucker says.

The expedition team surveyed a few miles of previously unknown territory in nearby Crystal Cave, slowly enlarging the cave system’s scope, mile by mile.

“What we found as we went along was one connection after another,” Brucker says. “It was then that we knew how vast the cave really was.”

One year after the NSS expedition, two of Brucker’s caving colleagues discovered the first official connection between Crystal Cave and Unknown Cave, both of which would eventually be included under the umbrella of Mammoth Cave. Now that explorers had mapped nearly 45 miles, the cave’s known passage system was growing in recognition. The National Park Service claimed the cave’s maps covered 150 miles, which put Mammoth Cave on record as the longest in the world.

Suddenly, Kentucky’s cave-dense karst area exploded onto the scene and attracted the attention of national publications. In 1955, Brucker and two of his partners led photographer Robert Halmi and journalist Coles Phinizy of Sports Illustrated through the recently discovered Eyeless Fish Trail in Crystal Cave. Because neither the photographer nor the journalist had any previous caving experience, it was up to the team to carry their weight. Brucker was burdened with the photograher’s waterproof box, which was filled with over 40 pounds of expensive camera equipment.

They arrived at an underground stream near their destination and the “trail” had turned to no more than steep banks covered in a foot of mud. Eventually they had to cross the stream over a bridge of mud. Brucker decided to get on his hands and knees. His crawling technique served him well until he reached the bridge’s halfway point. He was alone now, having to bring up the rear because of his slow pace. Moving his hand forward, he shifted his weight and let his hand sink through the cool mud.

All of a sudden, he was no longer on his hands and knees but on his stomach, sliding down into darkness. When his face hit water, he knew he was in trouble. His only light source was now extinguished, and with no reference point above or below, no hopeful beam of light to direct him, Brucker was lost.

“When you’re in utter blackness, sinking farther in the water, it’s the kind of thing that makes your whole life flash before your eyes,” Brucker says. “All I could think was ‘don’t panic.’”

Underwater, Brucker knew the only way he would find air is if he tried to swim in some direction. With all of his gear on, and the photographer’s waterproof box still in tow, his body sank like an anchor. Unfortunately, Brucker was swimming the wrong way, which he knew as soon as he knocked his head on an underwater ceiling.

“At that point, I realized I must be in some rain-barrel-sized hole, one of a series of small, underwater caves I’m sure,” he says. “When I couldn’t find the surface, I absolutely panicked.”

By pure luck—and a great deal of thrashing—Brucker eventually surfaced in a pocket, sputtering and gasping for air. He cried out for help, still totally disoriented in the suffocating darkness.

Brucker’s team heard his struggles and finally found him, though the photographer was more worried about his cameras than Brucker’s near-death experience.

“Obviously I made it out okay, but it shook me up for quite some time,” Brucker recalls.

He didn’t stop caving, however. In fact, he would go on to help link Mammoth Cave’s system from just over 100 miles to the present-day 400 miles. According to Brucker, exploration in the cave will continue at this impressive rate long after he steps down from the caving scene.

“If we can continue to add seven or eight miles to the system per year, there’s no doubt in my mind that Mammoth Cave’s reach will extend to 1,000 miles by the end of the century.”

Caving for What?

Unlike mountaineering or even paddling, there’s no grand summit during a caving expedition, no singular moment to work toward, no take-out at the end of the day. A constant desire to find out what is around the next corner continues, and will continue, to drive cavers of every generation toward some yet-unknown goal.

“Potential for further exploration is almost unlimited,” says Dave West, the Eastern Operations Manager of the Cave Research Foundation (CRF). The Mammoth Cave system is surrounded by other large cave systems, including Fisher Ridge, nearly 120 miles in length. It’s only 300 feet away from one of Mammoth Cave’s entrances, but it has yet to be connected to the system. Underlying politics between organizations have thus far prevented the connection of the two systems, but there is strong speculation that they share passageways and the discovery of their connection, if possible, will only be a matter of time. Though Mammoth Cave is the longest in the world, it is relatively shallow, which means any added mileage will come from cavers pushing the boundaries outward, not down.

“One passage we are exploring is in Great Onyx Cave,” says West, referring to a smaller cave within the national park’s boundaries. “It has the potential to connect into the system, but exploration there is weather dependent, so it is unclear when that may happen, or if it is in fact possible.”

CRF also helps protect more than 130 different species of crustaceans, fish, insects, and other inhabitants of Mammoth Cave.

“We cannot be certain we even know the full scale of habitation,” says West. “Each cave is a unique environment, and it is not uncommon for a single cave to have one or more inhabitants that are not known to live anywhere else. Consequently, many unique species are endangered immediately upon discovery.”

Like many caves throughout the region, bats are particularly at risk due to White Nose Syndrome, a fungus that interrupts hibernation cycles. The effect of a weakened bat population extends far beyond the daily life of a cave; without bats, increases in certain insect populations (which would normally serve as a food source for bats) could wreak havoc on nearby agriculture. Other cave-specific species that are at risk include the Kentucky cave shrimp, the eyeless cave fish, blind beetles, and cave crayfish.

“Caves are important to all of those that live near them,” West says. Unique microbes might be found that could provide a path to a cure for disease. We must protect what might well be the last unknown frontier.“