At this very moment, there’s an adventure-hungry soul somewhere in North Carolina sitting in front of the computer, refreshing 10-day extended forecasts every hour, hoping, praying even, for freezing temperatures.

He has his hooky excuse on standby, gear crammed in the trunk, fuel tank loaded. Why? Because climbing ice in North Carolina is like being on call—“If [the ice] comes in and you’re not ready to go, it can be gone the next day.”

So says Michael Neuenschwander, 47, of Asheville, N.C. Neuenschwander is a physician at Park Ridge Health, so he’s used to the get-up-and-go mentality. In nearly 20 years of ice climbing, Neuenschwander has ascended most every ice route in North Carolina and ventured well beyond the Blue Ridge to the legendary flows of Banff’s Icefields Parkway, Ouray, Colo., and the eastern Sierra. He has navigated crevassed, avalanche-prone terrain in a whiteout, self-arrest while soloing North Carolina’s Celo Knob, and army crawled for hours through rhododendron-choked forests in search of ice.

But for Neuenschwander, all of that is par for the course when your sport of choice is as ethereal as the ice on which it depends.

“Ice climbing is one of those sports you wonder why it’s worth it,” he says. “Sometimes you do find that it is quite dangerous. You are climbing this medium that changes from day to day, and you have to have more wits about you to climb that type of medium. Once you do, there’s this fluid nature to the climbing that is sorta monotonous. The feeling that you get climbing a sheet of ice just on ice tools and crampons is really like no other feeling.”

Not to mention that that feeling, that quiet moment of climber-on-ice, is but a fleeting image. With unpredictable cold spells, bouts of rain, and temperature inversions, the ice climbing season in the South sometimes amounts to a few weeks or less. In turn, the ice itself can often be fragile and detached. But, not always. So why do it? Why bother climbing ice in the South?

“Sometimes there’s rock you have to climb on. Sometimes you have to use rhododendron to belay off of. There are always varying conditions. But those are the toils of climbing ice in North Carolina. When it does come in, it’s as good as anywhere in the country.”

So suit up and get ready for some tales from the flows. Patagonia founder Yvon Chouinard once said, “When everything goes wrong, that’s when adventure starts.” If adventure is what you’re after, you’ve come to the right place.

UP SHIT CREEK WITHOUT A… TOOL

The year is 2007. The routes at Whitesides are in. Then 23-year-old Mark Rineer of Lancaster, Penn., is with his buddy Tony. Rineer is fresh off an ice climbing trip to Colorado. His body feels good, strong. His mental game is on point.

Together, the pair begins the day by warming up on the single pitch routes above Mother Russia and Starshine, the latter of which they intend to climb later in the day. They’re moving swiftly through the holds, freesoloing the first couple of routes without incident. Rineer eyes a pitch that’s pretty vertical, maybe a water ice 4 (WI4) grade, but he’s not intimidated. He ties in and starts up the 90-foot route.

Slowly, methodically, he works his way up the flow, places one screw, then another. His forearms start to burn and he scans ahead, searching for a rest amid an otherwise vertical-smooth canvas. It’s looking pretty dire, pretty blank. But then, not 20 feet above, he spots it—a ledge, or so he thinks.

“In hindsight, you know, it’s the kinda thing where it’s a coin toss,” Rineer says. “Stop and place a screw and get pumped out or gun for a rest? That’s a choice you make whether you’re leading trad climbs or ice climbs—place gear or stick to that ‘when in doubt run it out’ kind of mentality?”

Unable to ignore the fatigue in his arms, Rineer decides to hightail it to the rest. He’s moving purposefully now, not faster, but with a sense of urgency. Soon he’s within arm’s reach of the ledge. He raises his ice tool and sinks its point into the ice. Immediately, the ice shatters, and Rineer is left on a small peninsula of ice amid a sea of rock.

He freezes. His position is precarious, at best. The rock above extends farther than his arm can reach to the next patch of ice. To downclimb would be an equal stretch, and a sketchy one at that. Squatting down, he tries to place a screw where his lower tool is still biting into the ice. It doesn’t take. He tries the rock instead, but it doesn’t hold.

Panic starts to set in. Rineer is well beyond pumped. Hastily, he places his tool into the rock and clips his rope in, hoping to shake out his arms enough to get the blood flowing. But when he shifts his weight, Rineer feels something give, and another wave of panic crashes down—his tool has just popped out of the rock and is sliding 20 feet down the rope to his last screw.

There, at last, the inevitable sinks in: I am a dead man.

“I’m basically sure I’m going to hit the ground. There’s nowhere to go,” Rineer remembers. “Maybe 15 minutes pass. It got to the point where I couldn’t hold on any longer. I just remember my hand melting off the tool. The instant I let go, I just felt relief from panic, like, it’s done, there’s nothing else I can do.”

So there, almost 50 feet from the base of the climb, 20 feet above his last screw, Rineer peels off the route, hurtling toward his belayer and what is sure to be his untimely death. His lower screws hold, but a few feet too late. Rineer hits the ground, his body sliding down a ramp until it stops, buried beneath six feet of snowdrift.

“I remember Tony was looking at my cartoon-style, person-shaped hole in the snow. He knew he was looking at a dead body.”

Except Rineer wasn’t dead. In fact, short of getting the wind knocked out of him, Rineer was totally fine. He blinked, started wiggling his toes and fingers, had Tony palpate and examine his spine, then proceeded to hike out.

It should go without saying that Rineer took a break from ice climbing—a four-year hiatus at that. But Whitesides, and North Carolina ice in general, still maintains a special place in Rineer’s heart.

“I like the idea behind climbing in the Southeast. It’s never going to be bolted and it’s never going to be casual. It’s going to stay wild and that’s what I remember most fondly about ice climbing in the Southeast—bold and adventurous and sometimes scary but that’s what keeps it fun.”

40 FEET TOO LATE

Mother Russia is the mother of all ice climbs. Spanning 230 feet from top to bottom, this WI5 route is every bit steep, scary, and committing. Even by North Carolina standards, Mother Russia is a beast.

Which is exactly why Lynn Purser, a math professor from Alabama, wanted to climb it.

“He’s hired me for a number of things over the years with all of these nutty objectives,” says Ron Funderburke, a head guide at Fox Mountain Guides.

So when Purser got serious about Mother Russia, Funderburke got serious about guiding it. He spent much of the winter of 2014-2015 scouting the flow and finally, after three days of cold temperatures, the route was in.

“Lynn had said, ‘Call me and I’ll play hooky or call in sick or whatever,’ but the day I wanted to climb it was the day it was getting warmer and he couldn’t come until the day after. The day after a warm day, who knows what kind of shape [Mother Russia] was going to be in.”

Still, Funderburke agreed, and two days later, he and Purser were rappelling to the base of Whitesides. Funderburke knew the start was notorious for thin, verglas ice that didn’t take protection very well, even on a good day. So when he found himself 10 feet, then 20 feet, then 40 feet off the ground and still unable to place any gear, it wasn’t like he was surprised. More like embarrassed.

“It’s this gamut you get into as a lead climber and a guide. I’m not happy about where I am but maybe I climb another 10 feet and the ice will get better. Soon I get 40 feet off the ground, and not only is it not better, but I don’t feel comfortable about downclimbing the stuff I got up.”

Purser, sensing Funderburke’s hesitation, tried to shout encouragements from below, something along the lines of, ‘Man, if it’s not safe, we’ll just wait for another year.’ But for Funderburke, that out came 40 feet too late. There was no turning back now. The only option was to keep climbing until he could get a screw into the ice.

“It’s sometimes harder when you have the option to fail. In this case, there was no option to fail. It’s just like, ‘gulp.’ I’m feeling a little bit of embarrassment because I’m a professional mountain guide and it’s a little stupid what I’ve managed to get myself into. That’s easy to swallow. Fear you pretty much have to swallow because you won’t survive if your legs are shaking or your fingers are quivering. Mother Russia’s the kind of climb that will lure you in and when you can’t turn around, you gotta sorta rally and get up it and figure out how to survive.”

Funderburke rallied. Finally, 90 feet from the base, the ice finally took a piece of pro. The rest of the route, by comparison, was a cake walk.

“He climbed it, he enjoyed it, we ticked it, then I did shots to calm my nerves, which he paid for.”

COMMITTED

It wouldn’t be an overstatement to say that Fox Mountain Guides owner and guide Karsten Delap has done it all. From teaching clinics at Michigan Ice Fest and Ouray Ice Festival to guiding clients around the world to exotic destinations like Chamonix and Aconcagua, Delap arguably spends more time on mountains than in his western North Carolina home.

That makes the little time he is home all the more special, especially if the ice is in.

During the winter of 2014, Delap found himself in one such layover between travels when the North Carolina cold snaps were particularly powerful. So powerful, in fact, that Looking Glass became a frozen waterfall.

“Looking Glass rarely comes in because it’s such a big flow. It just doesn’t freeze up,” Delap says.

But that year, the 60-foot waterfall was frozen solid, save for the surging river-left side of the falls.

Despite being unable to hear his belayer over the roar of the unfrozen falls, Delap started up Looking Glass, relying on his and his belayer’s guiding experience to keep the climb within risk management—after all, Delap volunteers with three local rescue teams in high angle, technical, and wilderness rescue.

With his fiancée standing witness, camera in hand, Delap deftly navigated his way through a cave-like section of mixed climbing that, even by his standards, was physically taxing. Heart pumping, head clear, Delap transitioned over to the main flow, a pillar of ice that was literally wet to the touch thanks to the day’s warming temperature. Unable to place any protection, Delap climbed higher, bear hugging the pillar with his legs to avoid shattering the pillar with his crampons. When he was nearly 40 feet from the ground, he finally sunk in a screw, the smallest one on the market. It hardly went in halfway.

“I really did that for everyone else to make them think I was okay,” Delap remembers. “Really, I was far from good. I was still free soloing. This was like climbing-at-my-limit hard.”

Delap persevered, no thanks to a handful of other screws with questionable integrity. Unable to see or communicate with his belay partner from the top, Delap set up an anchor, pulled the rope taught, and began to belay. The duo topped out and rappelled, all without incident. It was only later when reviewing the images his fiancée shot that Delap realized that nearly one-third of the ice had fallen away while he was climbing it.

“To me North Carolina ice climbing has made me the ice climber that I am because I get to places like Canada and I’m like, “Oh my God, this is easy.” The ice climbing here is so fickle and you gotta worry about so many things.”

Karsten Delap’s Go-To Gear

As Fox Mountain Guides owner, guide, and head of Alpine Programs, Karsten Delap is well-versed in the ways of the mountain. He’s climbed all over the world, from Canada to Chamonix and everywhere in between. Check out his favorite pieces of gear for ice climbing in North Carolina and beyond.

Ice Gear

Julbo TREK with Zebra Lenses ($180)

These glasses allow you to see when in the shade, but as you top out in the sun, they darken so as not to be blinded.

Layer wool next to skin for all day warmth and comfort. Ranges in thickness from 1–3mm.

Good all-around ice tool that excels in pure ice and vertical mixed terrain.

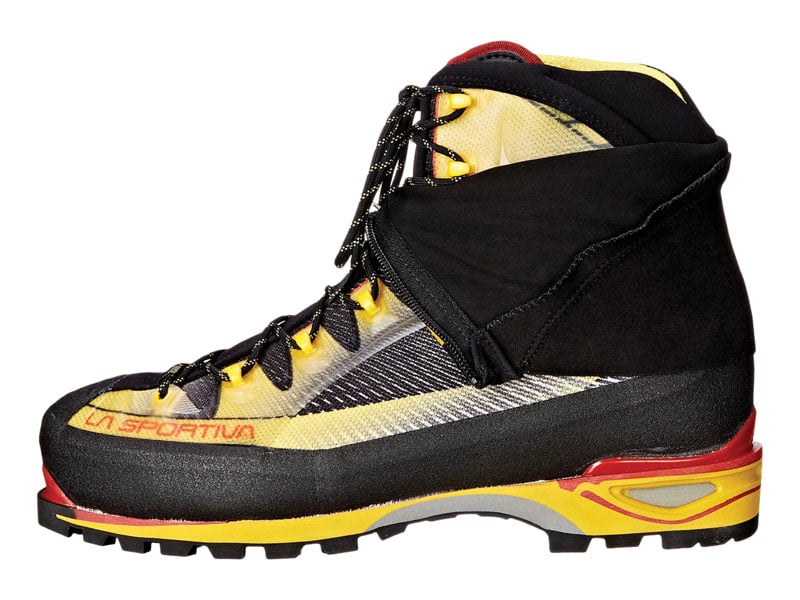

La Sportiva Trango ICE Cube GTX ($550)

The best, light ice climbing boot made. Excels at hard ice in warmer temps and overhung mixed terrain.

An alpine pack that carries ice tools well and has plenty of space for all of the extras but is still light and fast and carries well on route.

The all-around crampon. These can be changed from mono to dual point for lower angle ice and glacier travel but still hook up in steep terrain.