Editor’s Note: Both the Blue Ridge and the Smoky Mountains abound with names that are deeply rooted in Native American culture and history. The names of places like Oconaluftee, Tuckasegee, and Nantahala can all be traced back to the Cherokee, while the term Appalachia itself is derived from the language of the Creek. In this installment of ‘Trailblazer Tributes’, we’ve taken one of these names—likely more familiar to you as a top-notch mountain biking destination—and unearthed the legend behind it—that of a little known Cherokee farmer by the name of Tsali.

Springtime at the mouth of the Nantahala River always brings dizzying changes, intoxicating aromas, and the mysterious whispers of nature’s cycle. For an old Cherokee farmer it should have been a remarkable time, but as he sat on his cabin porch smoking tobacco, troublesome news occupied his thoughts. A powerful force threatened his beloved ancestral homeland, his farm, and his family. While great life-giving forces worked magically across the landscape of his mountain home, a horrible death march loomed on the horizon in the land of the setting sun.

Very little is known of the Cherokee Indian Tsali. According to the 1835 census, he lived with his wife and his three sons in a cabin where the Nantahala River drained into the Little Tennessee. Although his birth date is unknown, he was roughly 60 years old at the time of the census. He farmed a small hillside plot and hunted wild game. He could read neither English nor Cherokee. If not for a short heroic episode in the autumn 1838, he would have passed into obscurity—another nameless victim.

From the vantage point of post modernity the American frontier and the native inhabitants have always seemed ill-fated, victims of inevitable and unrelenting progress. Yet for many years the Cherokee coexisted with whites in the small agrarian republic of the early United States.

Beginning in the 1790s the Cherokee freely adopted white lifestyles. They built churches, schools, mills, and cultivated farms. Cherokee chiefs tolerated the occasional broken treaty, and when grievances arose they traveled to Washington to meet a U.S. senate committee and plea that they might maintain “the blessings of civilization and Christianity on the soil of their rightful inheritance.”

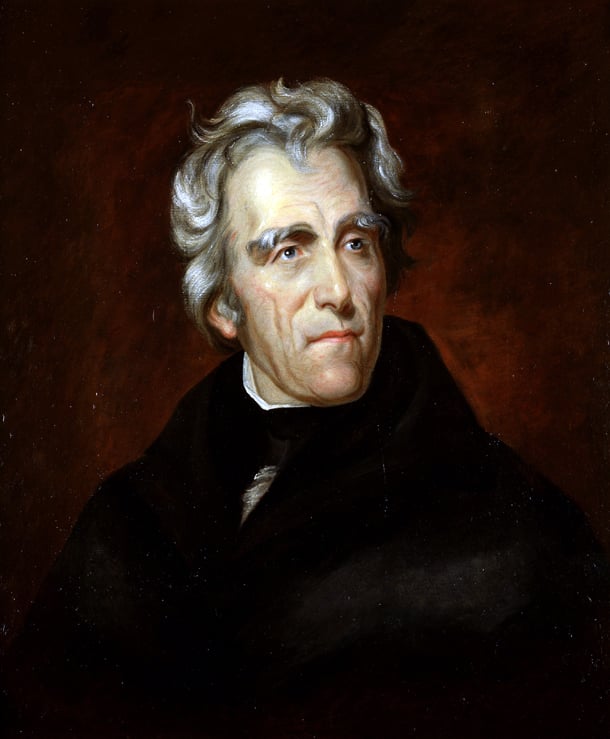

For Tsali and the rest of the Cherokee Nation their rights as Americans, and human beings, would rapidly erode after the election of 1828. Old Hickory, better known as Andrew Jackson, came to the presidency in the age of American democracy.

“The majority is to govern,” Jackson declared, and with that majorities in Georgia, North Carolina, and Tennessee quickly laid plans for the displacement of the Cherokee. With Jackson’s federal troops in tow they had the muscle to get it done.

In the summer of 1838 General George Winfield Scott, with a force of 7,000 soldiers, began rounding up Cherokee and detaining them in holding pens in Bushnell, where they would await the march west to Oklahoma.

Legend says Tsali dreamed of a resistance. Almost every Cherokee, it is safe to say, yearned deeply to remain in their native hills. In late October second Lieutenant Andrew Jackson Smith and three soldiers invaded Tsali’s cabin.

At gunpoint they forced his family, as well as his brother’s family, to gather whatever they could carry and march toward the stockade in Bushnell. Along the route soldiers began to prod Tsali’s wife with their bayonets.

Unwilling to accept such degradation, the prisoners began their rebellion. Speaking secretly in the Cherokee language, Tsali and his fellow captives devised a plan to overtake the soldiers. In the ensuing struggle, a rifle discharged, leaving one soldier with a mortal head wound.

According to the U.S. Military records, one of the captives drew a concealed axe and tomahawked it into the skull of a soldier. Lieutenant Smith fled for his life. In Bushnell he herded the previously captured Cherokee to Fort Cass in Calhoun. Meanwhile, Tsali’s party of 12 made their way north into present day Smoky Mountain National Park. Oral tradition maintains that they hid in a cave below Clingman’s Dome. On November 6, Colonel William S. Foster received orders to hunt down the fugitive band. General Winfield Scott, meanwhile, tactfully enlisted the dark forces of betrayal. “The individuals guilty of this unprovoked outrage must be shot down,” Scott declared.

The Quallatown band of Oconaluftee Cherokee Indians lived outside of the Cherokee Nation, and although they were not required by law to emigrate, they were nonetheless threatened by the 1830 Indian Removal Act. Chief Drowning Bear and his white adopted son William Holland Thomas brokered a deal with General Scott that if they did not harbor fugitives and delivered Tsali’s band, they would remain in Quallatown on the Oconaluftee River.

Tsali’s and his fellow renegade farmers shivered through the frosty nights of the late fall, while Colonel Foster, nine companies of the fourth infantry, 31 Oconaluftee Cherokee led by Tsali’s former neighbor Euchella, and William Thomas Holland tracked the runaways like wild game.

Cherokee legend says that Tsali learned of the agreement between the Oconaluftee and the Federal Government and willingly handed himself over as a sacrifice. Tsali, it is said, offered his own life if it meant his brethren could remain in their homeland.

The official record suggest that Tsali never surrendered. Throughout November, soldiers captured and executed Tsali’s relatives Jake, George, and Lowan. Eventually the search party apprehended the rest of his family, killing his two eldest sons, while sparing his youngest boy, as well as his wife.

The military continued their hunt for the four remaining fugitives, whom they regarded as the principal culprits in the upheaval. Soon only Tsali remained at large and with December approaching and their mission basically completed Foster’s troops pulled out of the mountains.

Shortly thereafter Euchella and his men caught up to Tsali, cornering him in a rock shelter in the Smokies. On November 26th, the Oconaluftee Cherokee marched their captured brother to Big Bear Reserve, now Bryson City. The men tied Tsali to a tree and prepared for an execution at high noon. Oral tradition claims that as Tsali faced six musket barrels, he refused to wear a blindfold, preferring rather to stare his betrayers directly in their dark eyes. It is likely that he could see his beloved hills in distance.

The historical and the legendary become clouded in the mists of time. Tsali’s tale is buried under the floodwaters of a TVA dam. It has been interpreted and retold by broken hearts. Records rely on broken treaties and the histories of ashamed parties.

Ultimately, it matters very little if Tsali willingly laid down his life or if he hunkered deep in caves evading his captors as best he could for as long as he could. It matters not if he refused the blindfold or if he stoically absorbed his assassins bullets in darkness.

Tsali, like Osceola, Chief Joseph, and so many others leaders of Native American resistance movements, bravely stood against the forces that fundamentally oppose human dignity and liberty. In that fight Tsali and his people lost a land that was blessed with life. Today they have reclaimed it, and as life-giving forces, like Elk and language, return to the Cherokee Nation, the young can stand on the shoulders of their forefathers, brave men like Tsali .