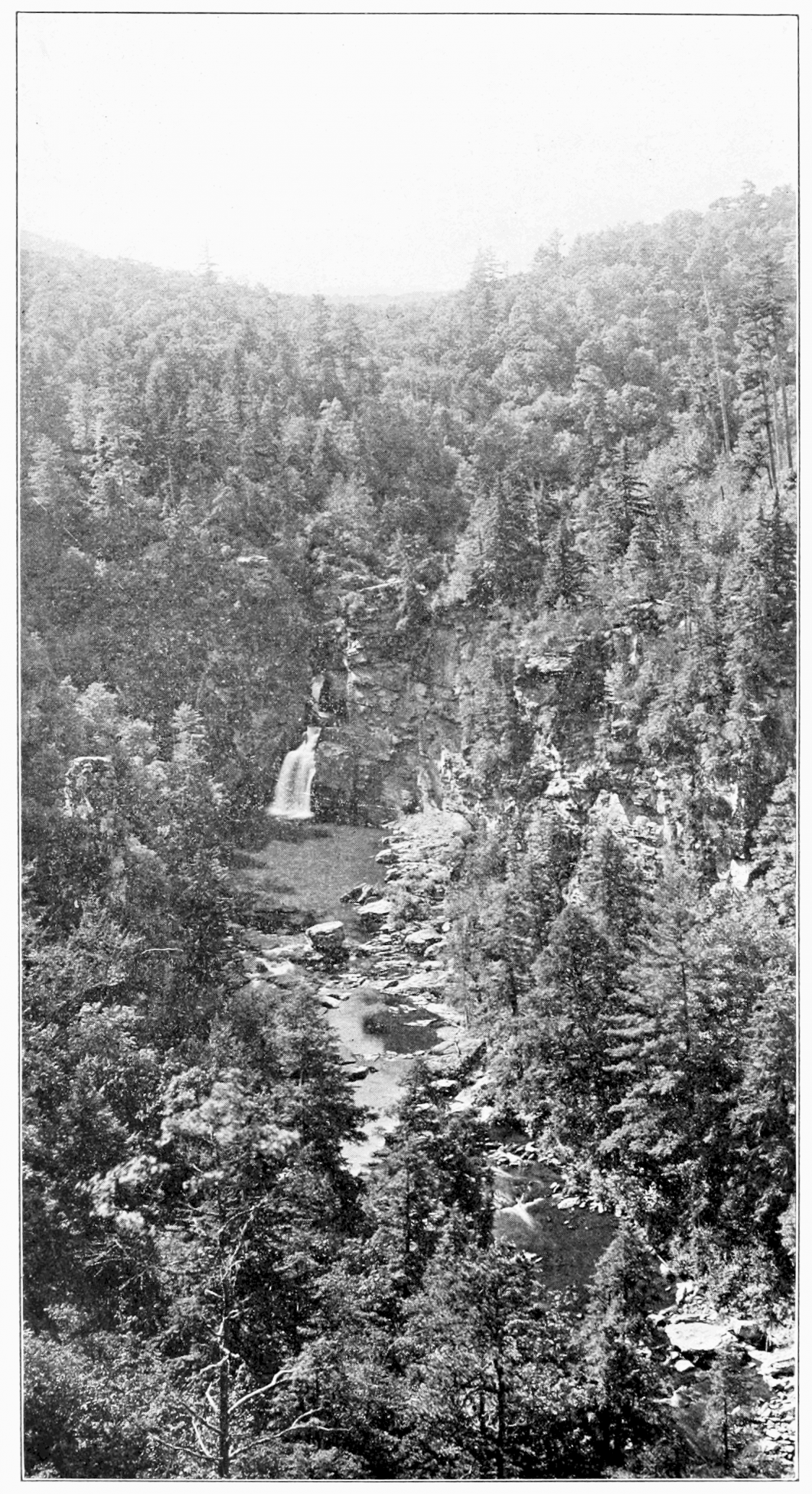

Editor’s Note: The Linville Gorge is one of the most rugged, remote and beautiful areas east of the Mississippi River. You may have seen photos of the gorge or you may even have been fortunate enough to visit this North Carolina wilderness gem for yourself, but did you ever stop to wonder how the Linville Gorge got its name? In the first installment of our newest series, Trailblazer Tributes, we’re diving deep into the story of this spectacular ditch’s namesake—a hearty frontiersman who went by the name of William Linville.

Along the banks of The Eseeoh-la, in a deep and dark gorge, William Linville suffered his final nightmare. Linville, like his famous nephew Daniel Boone, was a long hunter. More of a vocation than an occupation, long hunters were hardy frontiersman who spent lengthy tenures in the Appalachian backcountry piling up pelts, dodging Indian war parties, and mapping westward routes.

Extended exposure calloused these explorers and equipped them with highly-tuned instincts, a survivalist’s sixth sense. Linville was 56 years old when he left his cabin that summer and entered the gorge. A lifetime in the wilderness had so deeply ingrained into his psyche that even his dream world alerted him to impending danger. And so, as Linville awoke from a disturbing dream in which an indian massacre swept down upon his camp, he moved quickly to save his son’s life.

In the early 17th century, a large number of families left Sussex, England and settled in William Penn’s Quaker colony, now Pennsylvania. John Linville was one of those Quaker pilgrims. Like so many others, he ventured west from Philadelphia and homesteaded Chester County.

Around this same time Squire Boone Sr., father of the famous pioneers Daniel and Squire Boone Jr., moved into the nearby Quaker community of Lancaster. The two families would eventually intertwine and forever share a unique place in the annals of frontier history.

John Linville’s wife, Ann Linville, gave birth to six children. Her first son William was born in 1710. William’s formative years were spent honing skills and mustering courage in Chester County’s surrounding wilderness. He learned to shoot a musket, track game, including panthers, and would have had some minor interactions with the Lenape Indians, with whom the Quakers are said to have maintained amicable relations.

William Linville found his destiny on the Wagon Road. The 455-mile trail was scratched, carved, and smoothed with the blood and sweat of a small fraternity of men: Linville, Boone, and Bryan. Eventually an entire nation would pour through this route. The place names along the winding tracks still offer testimony to the perseverance of America’s geographical founding fathers. The great road ran south from Pennsylvania into Virginia and eventually on to North Carolina and still deeper south before bending to meet Kentucky’s Wilderness Road. Linville, along with other members of the New Garden Quaker community, loaded their Conestoga wagons and pushed into Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley sometime around the mid-to-late 1720s.

In what is today August County, Virginia, Linville joined the militia and worked his way to captain. Linville was more long hunter than soldier. Although a frontiersman could hardly be described as having a specialized occupation, Linville made handsome wages trapping in the backcountry. With a seemingly endless expanse of virgin woods prime for reaping, Linville, Boone, and hundreds of other vigorous souls disappeared into the Appalachians for months, or even years at time. Traversing gorges, and tackling summits, long hunters like William Linville not only provided valuable bundles of fur, but also new knowledge of formerly uncharted territories. Thanks to European markets, otter and beaver pelts fetched $7, while deerskin garnered $1, or a buck. The long hunters’ valuable cargo, and their constant encroachment on the sacred Indian game lands, made them vulnerable targets.

“Traversing gorges, and tackling summits, long hunters like William Linville not only provided valuable bundles of fur, but also new knowledge of formerly uncharted territories.”

By the late 1740s the Linvilles were once again ready to pull up roots and forge their way into unsettled territory. Through Herculean efforts, Captain Linville, alongside his father-in-law Morgan Bryan and George Forbush, extended the wagon road south and replanted their families in North Carolina’s Yadkin Valley. Yadkin, derived from the Soiuan word Yattken, means “place of big trees”. The Virginian families went to great lengths to reach this verdant valley. As described by Moravian Leonhardt Grubb, the founder of Winston-Salem, Linville and Bryan, over the course of three month’s hard travel, forded rivers, fought off predators, and even tore their wagons apart and manned them ‘piecemeal’ over mountain tops. Around 1749 Linville built his family a cabin along the Yadkin River on what is today Tanglewood Park in Forsyth County. The Boone clan was also among the first settlers to the region. The Yadkin became synonymous with the wilderness education and exploits of Daniel Boone. The Linville’s and the Boone’s soon became relation, as Rebecca Bryan, Ellender Linville’s niece, married Daniel Boone. William and Ellender had eight children of their own, and in 1763 Daniel Boone’s younger brother George Boone married their 24-year-old daughter Nancy Linville.

Survival on the North Carolina frontier demanded prioritization. Daniel Boone, for example, received no formal schooling and became a full-time trapper by the age of 15. Typically alone, Ellender and Rebecca raised large families and tended to the demands of the homesteads. They could go years at time without their husbands, as the long hunters pursued buckskins, elk, and buffalo in the fall and river pelts through the winter. At times Indian wars spilled into the valley. The entanglements of the French and Indian War, encroaching settlers, and skirmishes between the English and Cherokee on the Virginia frontier created a turbulent atmosphere in the late 1750s. The Yadkin became unsafe for pioneers families, and the Boone’s took temporary leave of the area. The record would suggest that Linville’s stayed during this period, which became known as the Cherokee uprising.

By the summer 1766 William Linville was aging and declining in health, and so he self-prescribed a long, arduous hunting trip. Linville, his 28-year-old son John, and a young man named John Williams, who would keep camp and cook, embarked into the Blue Ridge Mountains. They journeyed from the Watauga River into a deep, rugged gorge that Native Americans called the “Land of the Cliffs.” The men made their way 10 miles down river of an impressive falls and camped along a boulder-choked river in the stomach of the gorge.

The men unknowingly fell asleep on the wrong side of Shawnee muskets. This Shawnee war party, mobilizing for a battle with the Cherokee, worried the white hunters would jeopardize their position. Before the light of dawn, a startling nightmare shook Linville from his sleep. Sensing danger, he warned his son and Williams to flee without him, as the young men would have a better chance to survive unencumbered by the old man. And yet it was too late for either Linville. The Shawnee volleyed through the trees, killing both Linvilles and badly wounding Williams. The war party left to recover the hunters’ horses, while Williams laid on the ground in utter agony.

Knowing the Shawnee would return for their scalps, he attempted a self-rescue on foot before abandoning the notion and surrendering hope. Miraculously, one of Linville’s horses returned to the site of the massacre. Williams climbed upon its back and, despite extreme pain, rode back to the settlements, where he delivered the sad news and eventually recovered. Once word reached the Yadkin, a party descended the gorge and recovered both bodies. Daniel Boone is said to have been among the searchers who found William and John Linville’s scalped remains.

Captain William Linville’s life left a grand thoroughfare in its wake. Americans pilgrimaging westward in search of a better life followed his very footsteps. He led this manifest migration from the gritty forefront and personified the destiny of a nation. But to the indigenous people, he was yet another incorrigible encroacher. He pushed the frontier, and, until in his death, the frontier pushed back. His fate was an inevitable consequence of an obsession with conquering the unknown. For better or worse, history belongs to such men, and today no visitor to the Blue Ridge mountains can enter that beautiful, rugged gorge or stare upon those remarkable cataracts and not mention the name of Linville. The Linville Gorge.

Related Posts: