It was the summer of 2013 when Erik Filep noticed the devastation. He and his wife were traveling from Central Virginia to Ohio to visit family, when seemingly out of nowhere the scene was completely different.

“One summer everything was fine, there was no noticeable damage,” said Filep, former owner of Filep Forest Management, a Virginia-based company that provides forest and wildlife management for landowners. “Then the next summer when we went back up, driving the exact same route, there were just dead ash trees everywhere. It seemed very sudden.”

Of course, as a forester with more than 10 years in the field under his belt, Filep knew the ash trees’ demise was anything but sudden. In fact, those trees had probably been slowly dying from the inside out over the course of at least a couple years, thanks to a tiny insect called agrilus planipennis, more commonly known as the emerald ash borer (EAB).

Experts agree that EAB is the most destructive threat facing Southeast American trees today, and the ash is one of many Southern trees in trouble. The list of specific pests and diseases is lengthy, but the most significant threats affecting our forests fall into two categories: invasive species and climate change.

Unwelcome guests

Filep and other experts agree that invasive pests like EAB, a green jewel beetle native to eastern Asia that feeds on the leaves of green, white, black, and blue ash trees, are at the top of an ever-growing list of threats facing southeast American forests.

An increase in global trade has made it easier for insects to cross oceans and settle in the U.S., and those freeloading travelers making themselves at home in our forests are causing tremendous long-term damage.

“The Southeast has a very similar climate to a large portion of Asia, and more specifically, China, which makes it the prime habitat for species found there,” Filep said. “This includes invasive species such as kudzu, tree of Heaven, Asian long-horned beetle, Japanese stilt grass and wisteria.”

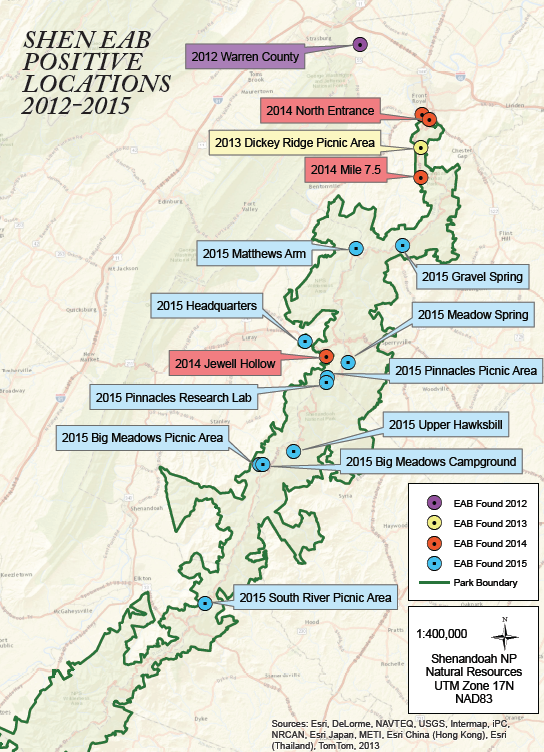

Rolf Gubler, a biologist who oversees forest health issues at Shenandoah National Park, noted that pests from other corners of the globe are able to thrive because there’s nothing here preventing them from doing so.

“Many pests do not have any, or enough, natural enemies or predators to keep them in check in their new location,” he said, naming the gypsy moth and universally detested stinkbug as two other invasive species that have spread with ease.

A green jewel beetle native to eastern Asia, the EAB is an invasive species in Europe and North America. After the females lay eggs, the larvae feast on the tree’s inner bark, hindering the flow of water and nutrients and ultimately girdling and killing the tree.

“Once the emerald ash borer infects the tree, it can take a while for the tree to die,” Filep said. “It’s very hard to notice that the tree is in trouble until it’s pretty much too late.”

The beetles arrived in the states in the 1990s, likely on hardwood packing material in cargo ships or airplanes from Asia. Since landing in the midwest more than 20 years ago, the pest has made appearances in 28 states including Virginia, West Virginia, North Carolina and Tennessee, killing tens of millions of ash trees. Adult EABs can only travel about a half-mile from the tree they emerged from, but the insects spread farther when people transport infested firewood, nursery trees or logs to non-infested areas.

Native to Asia, the emerald ash borer is merely a nuisance to the ash trees over there and is typically found in low densities. But as an invasive species in the U.S., they are now considered to be the most destructive forest pest ever seen in North America.

Oak trees in the region are also threatened by a new pathogen. Bot canker—caused by the fungus Diplodia corticola—was observed in West Virginia for the first time last fall. The fungus limits the ability of oak trees to access essential nutrients and water, ultimately killing them. So far, it’s affected only small numbers of oaks, but it has the potential to be widespread, especially as other environmental stressors weaken trees.

Have we been here before?

This certainly isn’t the first time we’ve watched as nearly an entire population falls victim to an invasive threat. According to Virginia Tech professor of forest biology John Seiler, the destruction of North American ash trees “could be the chestnut all over again.”

The chestnut was the sweetheart of American hardwoods. Wildlife and humans alike revered and relied on its sweet-tasting nuts that fell in the fall, and the tree was one of the most predominant species in Eastern forests. One in four trees in the East was a chestnut.

Today, there are almost no mature chestnut trees. The species succumbed to chestnut blight, caused by an Asian bark fungus beginning in the early 1900s. By the 1950s, billions of chestnut trees from Maine to Georgia had died slow deaths, permanently reshaping the forest landscape in the eastern U.S.

Other trees like the red oak filled in its niche, but without the chestnut, Eastern forests produce less food for wildlife.

Should we try to stop the spread of invasive species and diseases? Virginia Tech professor of forest biology John Seiler said he is, generally speaking, in favor of human intervention. Though he has yet to witness a success story, that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t at least try. If humans are responsible for the infestation of a destructive, invasive species, Seiler believes we have a certain level of obligation to try to get rid of the threat or at least slow down the damage.

Filep agrees. “I think we have a responsibility, when we introduce something into the environment, it should be our place to try to fix it,” Filep said. “I feel that way about a lot of invasive plants, too. Almost all were introduced for erosion control, landscape trees, all sorts of idiotic reasons that were well-intentioned but went horribly wrong.”

It’s getting hot out here

According to the Environmental Protection Agency, forests occupy about 740 million acres in the U.S., which is about one-third of the nation’s land area. And as global temperatures continue to climb, it becomes harder for those forests and their ecosystems to function and thrive. According to Gubler, trees adapted for northern climates that are found primarily on mountaintops are especially threatened by climate change.

“Examples at Shenandoah National Park include the balsam fir and Canada yew at high elevations,” he said. “As temperatures increase, trees adapted for northern climates that are found in isolated populations at the tops of mountains will eventually phase out.”

As global temperatures continue to climb, species either adapt or they don’t—some species will flourish and others will decline.

“The irony is that many of the invasives will just shrug their shoulders and be stronger, and many natives will have more trouble,” said Mike Van Yahres, owner and operator of the 97-year-old Charlottesville-based Van Yahres Tree Company.

The hemlock woolly adelgid, for example, a ruthless invasive pest that destroys Eastern hemlocks, is sensitive to cold temperatures. Rising temperatures allow the small, aphid-like insect that sucks the sap out of hemlock and spruce trees, to travel farther and spread more indiscriminately, wiping out thousands of trees in its wake.

Hemlock, stock and barrel

Also native to Asia, the hemlock wooly adelgid was first reported in the U.S. in the 1950s near Richmond, Virginia.

According to Gubler, hemlocks are “sort of a niche species,” growing alongside streams and other waterways to create cool, dark microclimates. By 2003, he said, Shenandoah National Park had lost about 95% of its hemlocks, which made up about 0.5% of the forest cover.

“It’s hard to replicate when you lose those trees,” Gubler said. “There’s really no replacement conifer that comes in and takes over, so we’ve lost a lot of those unique microclimates.”

The good news is that a handful of the trees did manage to hang on, and hemlocks are easier to treat and more likely to recover than ash. The NPS’s suppression plan involves two systemic pesticides, both of which contain imidacloprid, a neonicotinoid insecticide that is highly toxic to aquatic insects and pollinators. When treating trees near bodies of water, they use soil injections of Prokoz Zenith, with imidacloprid as its active ingredient. Using one of these two systemic insecticides, Gubler said they’ve treated roughly 2,000-4,000 hemlocks per year since 2006 using soil injections, and there’s been a noticeable improvement.

“I think overall the outlook for hemlocks in the park is a lot better,” he said. “You can turn around a hemlock that’s 60 percent gone, whereas with the ash, the emerald ash borer gets under the bark layer and has a girdling effect, and you can’t bring that tree back.”

Nature vs. nurture

A third generation arborist, Van Yahres is the grandson of a “tree surgeon” who was invited by the Garden Club of Virginia in the early 1920s to restore some of the historic trees at Monticello.

“In doing so he started working with the farms and estates in Albemarle and surrounding counties,” Van Yahres said. “He wanted to preserve their old majestic trees and he had the resources to do it.”

Van Yahres said he and his team are also some of the most “active environmentalists in what has historically been kind of a chemical industry.” His primary concern is that property owners will spray indiscriminately, killing the pest or disease in question but also eliminating other beneficial insects in the process.

“Historically when we intervene on things like this, we’re oversimplifying and the argument could be made that we make it work,” Van Yahres said. “Killing one bad thing in exchange for killing a whole lot of good things is not keeping the balance of nature.”

Take the gypsy moth, for example. Accidentally introduced in Massachusetts in the 19th century, the gypsy moth is known for its tremendous defoliation impact on hundreds of North American deciduous tree and shrub species including maple, elm, and oak. The notorious hardwood pest has destroyed millions of trees since the first outbreak in 1889. Over the years, natural predators like stink bugs, parasitic wasps and flies, Calosoma beetles and small mammals like mice and chipmunks have contributed to keeping the gypsy moth populations under control between outbreaks.

“Now that it’s been here for a while, nature has come up with a whole bunch of enemies of the gypsy moth, and it’s no longer as big of a problem,” Van Yahres said.

Nature is resilient, but the loss of a key species like the ash tree will diminish the health and productivity of the forest for millenia. Gubler leads a team of forest researchers on projects to treat individual trees throughout the vast Shenandoah National Park. He believes in human intervention, but at the same time he’s realistic about the current threats and how forests will adapt.

If you are looking at forests from a native species integrity standpoint, then the long-term outlook isn’t great,” Gubler says. “The forest will still be green, but there will be less forest diversity and overall biodiversity as a result.”

Do your part

So what exactly can we do to help? Even without a forestry degree or experience as an arborist, here are a few ways you can contribute:

Don’t transport firewood

As appealing as it may be to dodge the cost of a bundle of logs by throwing some sticks from the backyard into the car before going camping, suck it up and pay the $10 at the campground. If EAB larvae live inside even just one piece of wood from your yard that’s moved to another location, they can emerge and infest the entire area, effectively spreading their destruction even farther.

Know the signs

If a tree in your yard is exhibiting signs of an infestation, contact an arborist immediately. They may not be able to save the tree, but if they remove it in time it could prevent further spreading.

Signs of EAB include serpentine galleries and D-shaped exit holes on the trunk, increased woodpecker damage, split bark and canopy dieback. Hemlocks infested by the HWA will have off-color needles that drop prematurely and white woolly egg sacs on the underside of twigs.

Donate

Organizations like the Hemlock Restoration Initiative, the Nature Conservancy, and the Shenandoah National Park Trust happily accept donations that go toward their research and efforts to combat threats like EAB and HWA. Also check out your local tree stewards.

next in line

Ash and hemlocks aren’t the only species of trees battling pests and diseases.

Tree: Dogwood

Threat: Anthracnose fungus

Symptoms: Tan spots and premature abscission of leaves, cankers on twigs, succulent shoots at the lower trunk, spotted flowers

“Anthracnose attacks when conditions are just right, and 99 times out of 100 it’s a one- or two-year problem that goes away and the healthy trees survive,” said Van Yahres.

Tree: Oak

Threat: Sudden oak death, caused by plant pathogen phytophthora ramorum

Symptoms: Leaf spots, cankers on the stems, twig dieback

“It’s a very fast-moving disease. Once it starts the tree can die within a couple days to a week. Literally a tree can be fine and then it’s dead,” said Filep. “Fortunately it has not been found in the east to my knowledge, but the entire eastern U.S. is in major threat territory for that.”

Tree: Pine

Threat: Pine bark beetle

Symptoms: Popcorn-sized lumps of pitch (or “pitch tubes”), S-shaped feeding cuts on the inside of bark, needle discoloration from green to brown

“The pine bark beetle came through with a vengeance 30 years ago or so, and it preyed on the weaker trees,” Van Yahres said. “From a forestry point of view the lesson is that when you plant too much of one kind of crop, it’s all susceptible to one kind of disease or pest. We don’t need to blame the pine bark beetle, we need to blame decisions made by people.”