On a cold winter day in January 2017, a pleasant day hike in the Shining Rock Wilderness area in Haywood County, N.C., turned into a life-threatening ordeal.

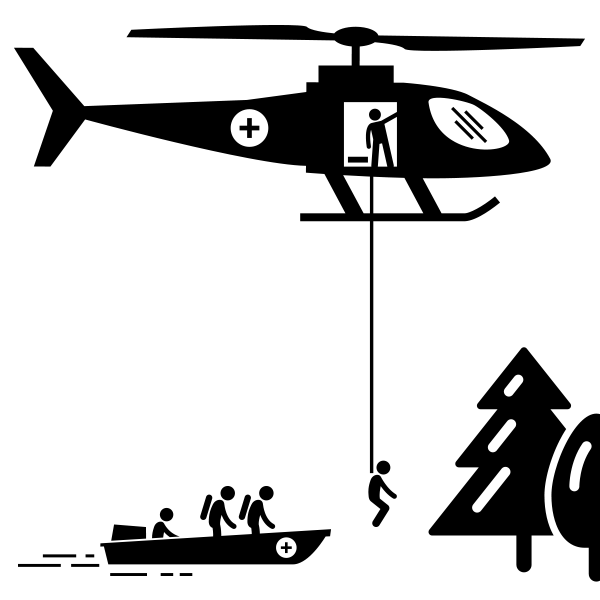

As the Citizen-Times reported, two men went missing for three days in the snow-blanketed forest after losing their way on the unmarked trail. Although they didn’t have food, water, or adequate clothing, and temperatures had dipped below freezing, they stayed put and built a fire after calling 911. Volunteer rescuers quickly realized they were out of their depth and wouldn’t be able to find the men before they succumbed to the weather. So they teamed up with the North Carolina State Highway Patrol, the North Carolina Emergency Management Helo Aquatic Rescue Team, the National Guard, and other organizations to probe the trackless wilderness from the air, using helicopters with night-vision equipment. After a massive effort that cost more than $14,000 and involved some 200 rescuers from 46 agencies, the men were located, having suffered only minor injuries.

Stories like this can make you feel conflicted: It’s great to read about a successful rescue, but it’s also easy to criticize the victims, second-guessing choices and identifying mistakes that seem obvious after the fact.

And then there are the costs involved, which can reach into the tens or even hundreds of thousands of dollars depending on the terrain, necessary equipment, number of rescuers, etc. However, although expensive rescues make headlines, they typically cost less than you might think. Robert Koester, CEO of dbS Productions LLC, a search and rescue training, research, and consulting firm, pegs the average cost of a rescue in Virginia at about $900, based on data from the International Search & Rescue Incident Database. For the National Park Service in 2012, the average bill wasn’t much higher at $1,804. Still, some argue that to encourage responsible behavior in the outdoors, individuals who get in trouble should have to pay at least part of the cost of their own rescues.

But many experts disagree. “I think making subjects pay for SAR response would not encourage people to make better choices and is full of unintended consequences,” such as discouraging calls for help when people are really in trouble, Koester says. National Association for Search and Rescue Executive Director Christopher Boyer agrees. “We do not have any evidence that a financial penalty would encourage residents to be more responsible,” he says. “In some cases, subjects have no education or experience that would tell them what the alternatives are in the decision making process, or which alternatives carried more or less risk.”

Costs aside, Jill Gottesman, a conservation specialist with the Wilderness Society’s Southern Appalachian office, says that local search and rescue teams have successfully partnered with management agencies to help rescues go more smoothly with the least amount of environmental damage. “We are really lucky to have the whole spectrum of recreational opportunities [in Western North Carolina], from remote Wilderness to roadside picnic areas, so we have to prepare for safety needs across the board but don’t want to detract from the incredible outdoor experiences that people are seeking,” she says. Gottesman added that the Forest Service should provide more resources—including for search and rescue—in the Nantahala-Pisgah National Forest management plan.

More money is always welcome, but it won’t make up for all the outdoor enthusiasts who rely too much on technology and not enough on common sense. Several experts say that a lack of basic outdoor education and preparation for the conditions of specific trips accounts for the majority of rescue situations. “I think we see people relying on technology as their safety plan,” says Charles Laird, emergency services coordinator for the North Carolina Department of Public Safety. “Technology like cellphones have made our daily lives easier and safer in some ways, but it has also increased our use and dependence on that technology. When those support systems are no longer available, folks that rely on them can find themselves in trouble pretty quickly.”

So before becoming judgmental the next time we read about another victim of a wilderness mishap who needed to be bailed out, let’s remember that it could easily be us—if not out in the boondocks on a high-risk expedition, then maybe on a short hike in the summer heat close to home after neglecting to bring enough water. While there’s never an excuse for tackling wilderness challenges unprepared, forcing people to bear the financial burden if they run into trouble will only lead to more victims.

Don’t become a victim

Jeff Caldwell of the Virginia Department of Emergency Management offers this advice: no matter how much experience you have, don’t wing it, and let other people know what you’re up to. “Always make a plan, and let someone know exactly where you are going and when you will return,” he says. “Stick to the plan, and check back in upon completion.” Even the best-laid plans sometime go awry. If that happens to you, Caldwell says, STOP (sit down and stay put, think, observe, and plan).