When I set off to hike the Appalachian Trail as a twenty-one-year-old and a recent college grad, I wasn’t forsaking my degree. I was continuing my education.

Two weeks into my five-month thru-hike I encountered a blizzard in Great Smoky Mountains National Park. I remember the fear and discomfort of trying to navigate the snowstorm and discern the inconspicuous white blazes amid blizzard-like conditions. At one point I was forced to cross an exposed ridgeline with the wind and snow buffeting my face. I felt the cold burn on my cheek, turned my chin away from the biting current, and closed my left eye. When I made it back into the sanctuary of the forest, I lifted my head up but something was wrong. I couldn’t open my eye. It had frozen shut.

I threw off my mitten and started picking icicles from my eyelids and wiping frozen crust from the corners of my eye. After an eternal minute, I was able to open my eyelid, regain bilateral vision, and continue marching down the mountain.

Hiking through a blizzard in the Smokies with one eye frozen shut taught me that I needed vision and wanted direction on and off the trail. As a backpacker, I had blazes and maps to show me the way, but I realized that I needed to make plans and set goals if I wanted to be equally successful in life. I also realized that it doesn’t matter how hard you are working if you are headed in the wrong direction. These weren’t classroom lessons; these were life lessons.

Joe Bandy teaches people how to teach. As a professor of Sociology at Vanderbilt University and Assistant Director of the school’s Center for Teaching, he has spent countless hours studying the most effective methods of teaching and learning, and he agrees that outdoor adventure can teach essential traits like critical thinking, humility and resilience.

“We test our bodies, minds, and spirits when we go outside,” he says. “It provides a time to set aside media, social media, work life and stress and provides a form of contemplation that can enhance focus and lead to greater critical thinking.”

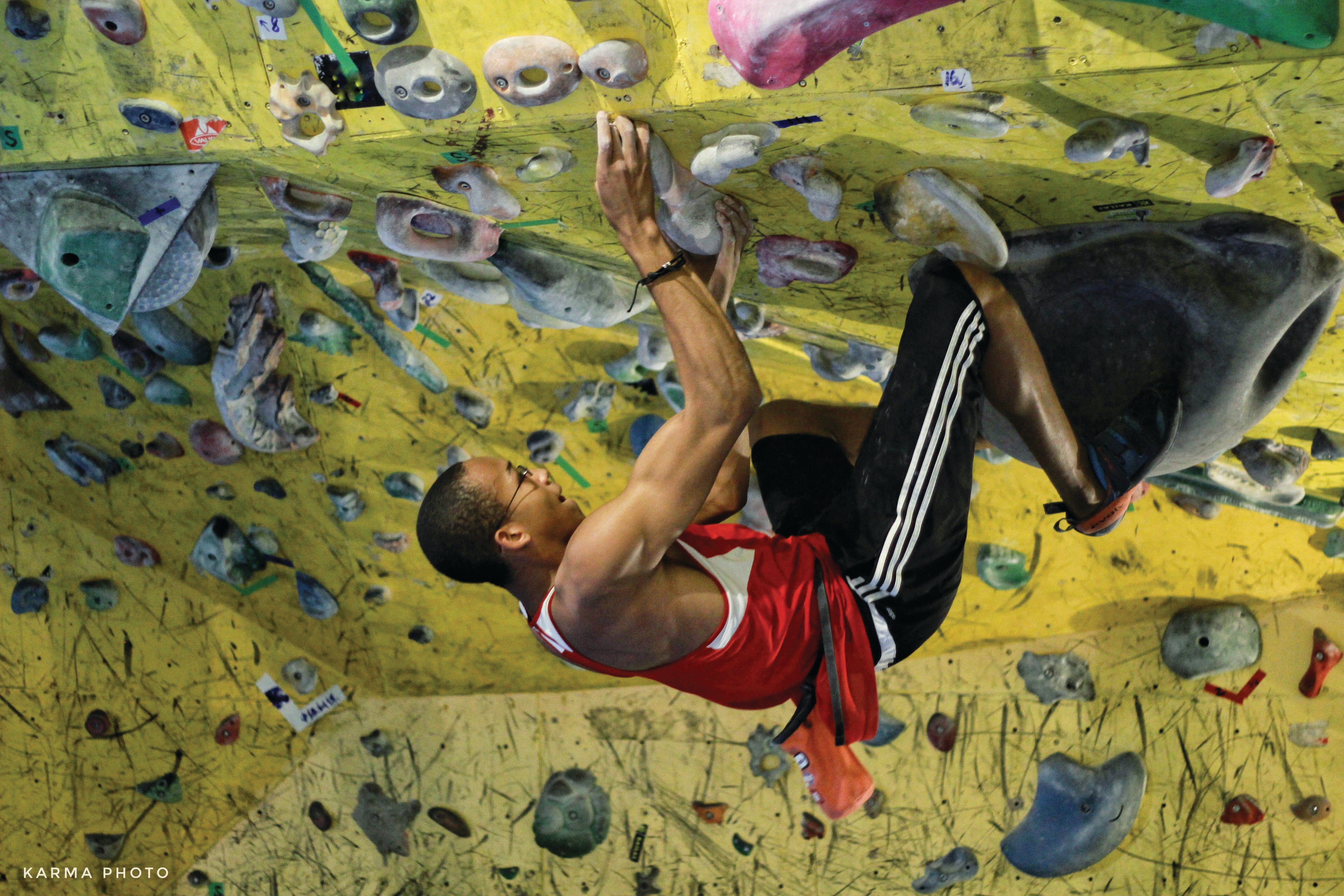

The positive effects of problem solving are demonstrated through the maturity and social awareness of up-and-coming outdoor athletes like Kai Lightner. Kai is a seventeen-year-old climbing phenom who has reached the pinnacle of his sport while also attending high school in Fayetteville, North Carolina. Kai explains that he often has to miss school to attend climbing competitions, but that his experiences in the gym and on the rock are just as formative in his intellectual and emotional development as a person. “The athletes at the top of my sport,” he says, “are not always physically the strongest; they are often the smartest. When I am at a competition, I have four minutes to preview a boulder problem and come up with the correct strategy to climb it, and try to complete it. It is the route-setters’ job to challenge us. I have to consider all the options in order to find the best solution. I’ve found that thinking outside the box is crucial in climbing and my classroom studies.”

“The athletes at the top of my sport,” he says, “are not always physically the strongest; they are often the smartest. When I am at a competition, I have four minutes to preview a boulder problem and come up with the correct strategy to climb it, and try to complete it. It is the route-setters’ job to challenge us. I have to consider all the options in order to find the best solution. I’ve found that thinking outside the box is crucial in climbing and my classroom studies.”

Kai also credits climbing with empowering him to perform under duress. “I handle pressure situations well because I’m used to having a lot of people watch me during events. I have super high goals for myself, and climbing has taught me that I probably won’t succeed the first time I try something. It’s taught me how to deal with failure.”

Professor Bandy agrees that outdoor sports and adventure pursuits can teach people to deal with failure and success gracefully. He gave the example of coaching and playing on an Ultimate team while teaching at Bowdoin College, which taught him the cooperative dynamics of outdoor athletics first hand.

“I saw the students hone their skills as a group,” he said. “I watched as they learned to develop team strategies and manage time. I witnessed their confidence and self-esteem increase.”

He also noticed that students interacted with him and one another much differently than in a strictly academic setting. The activity provided a means for the group to work towards a common goal. “We were learning socially and emotionally from one another in a way that doesn’t happen in the classroom. There was a collective sense of achievement.”

Rock climbing is a more solitary pursuit, but whether Kai is scaling the 5.14d rated Era Vella in Spain or participating in the Youth World Championship, he believes travel and competition have helped him to become a more compassionate person who relates well to others.

“Climbing has allowed me to travel and interact with a wide variety of people,” he says. “It makes me want a diverse and active social life. Even when I’m competing against someone, we usually feel a sense of camaraderie. We’re all experiencing the same stressful scenario and we identify with each other’s sentiments. Rock climbing hasn’t just taught me how to compete; it’s taught me how to be more empathetic.”

Kai and Joe are both leaders in their respective fields and have seen the positive impact of outdoor adventure in their academic settings. As a wife, mother, and business owner I can also attest to the fact that outdoor adventure has equipped me with skills to better grapple with the mundane tasks and endless chores that constitute my work–life balance.

In 2011, I was trying to set the Fastest Known Time on the Appalachian Trail. After nearly a fortnight of suffering filled with agonizing shin splints, a brutal sleet storm, and a devastating stomach bug, I stumbled to a road crossing in central Vermont where my husband was waiting anxiously for my arrival.

I promptly sat down and started sobbing.

“This is it. I’m done,” I said. “I can’t go any farther.”

My husband put his hand on my back and said, “You can’t quit right now. Right now, you feel too bad to make a good decision. You’ve given too much to give up now, so try to keep going a little farther.”

Through the physical and emotional pain, I kept going… a little bit farther… then a little bit farther… then after 46 days of going “a little bit farther,” we made it to end. We set the record, but just as importantly, we did more than what we thought possible. And we did it as a team.

In my everyday life, the mountains that surround me are comprised of piles of laundry that need to be folded, stacks of dirty dishes in the sink, and mounds of paperwork on my desk. But, I still draw on my experiences from the trail to help navigate these obstacles. And when it’s 11 PM and I am working towards a writing deadline that is interrupted by a crying newborn, I frequently tell myself “just a little farther.” I know how much you can accomplish when you are willing to keep going.

The Appalachian Trail taught me lessons I never learned in school. Before my thru-hike, I’d traveled the trail of convention and expectation that was laid out for me. After, I steered my path toward innovation and entrepreneurship. Tolkien famously said, “All who wander are not lost.” And when I trade stories and compare notes with folks like Joe and Kai, I’m reminded that whether you are a full-time student, teacher, parent or professional, outdoor recreation can be a valuable part of your education.

Adventure is responsible. And it’s a whole lot cheaper than grad school.