IN THE FOOTSTEPS OF APPALACHIA’S FIRST PEOPLE

Before there were roads, there were only trails. Before there were wheels, there were only feet. Before the Norsemen and Columbus stumbled upon North America, the continent was crisscrossed by a trail system chiseled into the earth by animals large and small and the silent moccasins that followed them.

Three hundred years ago, the southern Appalachians were home to the sovereign Cherokee Nation. Over sixty towns and settlements were connected by a well-worn system of foot trails, many of which later became bridle paths and wagon roads. This Indian trail system was the blueprint for the circuitry of the region’s modern road, rail, and interstate systems. Cherokee towns and villages were scattered across Southern Appalachia. The most isolated of these towns were in the remote valleys of western North Carolina along the Little Tennessee, Cheoah, Valley, Hiwassee, Nantahala, and Tuckasegee Rivers. Mountainous barriers reaching into the sky surrounded these towns and European explorers described them as “impassable” on early maps.

For the past seven years, I have stalked ancient trails across the Cherokee Mountains—the Appalachian Mountains as they are known today. I have driven on trails now paved over, and I have floated rivers that parallel trading paths. Some of these paths were used in the 1838 Trail of Tears when most of the Cherokee Nation was forced west.

To map these trails, I hiked through chest-high stinging nettles and slithered on my belly through laurel thickets and around steaming piles of bear scat. One trail up the Snowbird Mountains crisscrossed a creek eighteen times within two miles. I got stung over a dozen times by yellow jackets on four different days, and was near hypothermia from a blinding rain storm that took us by surprise on Chunky Gal Mountain.

These trails are not to be confused with modern recreational trails, although portions of some of them have become a part of the Appalachian, Bartram, and Benton MacKaye Trails. They are abandoned and deeply entrenched in some places, and overgrown in rhododendron and laurel in others. Sometimes a trail abruptly disappears where early 20th century logging operations stripped the mountains of trees. We can stand in the deeply worn recesses and look at the distant profiles of the mountains from the exact vantage point of Cherokee ancestors a thousand years ago. These trails were the travel arteries of the land, the highways of their day, and they connect our generation with the history of the land.

When I am not on the trail, I live in a world of old maps, survey plats, journals, 18th and 19th century land deeds, and historical archives, that over time have become assimilated with modern topographic maps and indelibly stamped into my mind as a layered and seamless, three-dimensional landscape. This ancient landscape comes to life through a piece of crumbling, hand-lettered parchment, a scrimshawed powder horn, or the silent voice of a traveler’s journal, mile by mile and stream by stream. I reconstruct the cultural landscape of those who knew these mountains before the Europeans came, gathering information from national and university archives and marking a verifiable course on modern topo maps. Then, wherever possible, I walk the trails. Researching and documenting Indian trails requires skill in cross-country navigation, the basics of land surveying, access to historic map collections and early records, and physical ability.

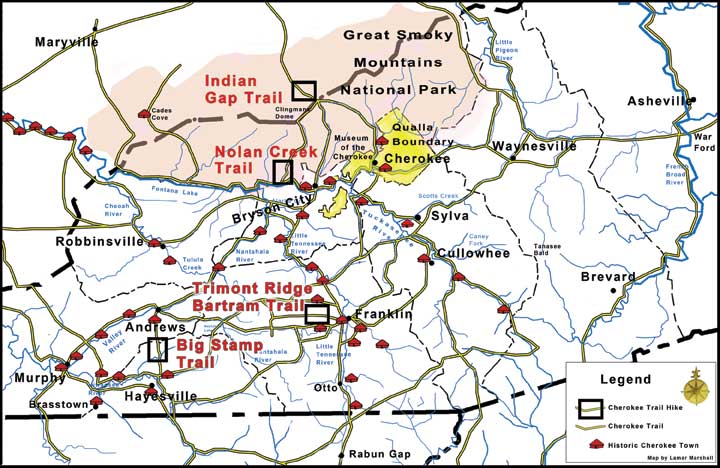

Noland Creek Trail (4.1 miles)

Great Smoky Mountains National Park, N.C.

Noland Creek Trail is identified as a Cherokee trail on early land records. It connected the Little Tennessee River Trail to Clingmans Dome, known to the Cherokee as Kuwahi or the Mulberry Place. Noland Creek Trail is also a section of the larger Benton MacKaye Trail. There was an Indian camp located near the junction of the creek and the Little Tennessee River.

Directions: From downtown Bryson City, take Everett Street across the railroad tracks and continue west on Lakeview Drive for 7.9 miles. There is a parking area on the left just before crossing Noland Creek.

Trimont Ridge Trail and Bartram Trail to Wayah Bald (10.8 miles)

Franklin, N.C.

The Bartram Trail Society adopted a section of the old Cherokee trail that followed Trimont Ridge. The trail is maintained and in excellent condition. I recommend beginning at Wayah Bald and following the Bartram Trail route east to Bruce Knob where it leaves the Cherokee trail and ends at the Bartram trailhead at Wallace Creek.

Directions: From US Highway 441/23 and US Highway 64 intersection south of Franklin, NC, head west for one mile and turn right on Sloan Road. Pass US Forest Service Nantahala District Ranger Office and turn left on Old Murphy Road. Turn immediately right on Pressley Road. At 2.5 miles pass Wallace Branch Road on left. Stay straight on what is now Ray Cove Road. At 3.6 miles park at Bartram trailhead.

Indian Gap Trail (3.3 miles)

Great Smoky Mountains National Park, N.C.

A well-preserved section of the Indian Gap Trail exists in Great Smoky Mountains National Park. This trail is known as Road Prong Trail on National Park Service maps. It’s an incredibly gorgeous walk with much plant diversity, old trees, raging mountain stream with falls and rapids. This trail is maintained by the National Park Service. The walk is easy. There are a few fords in the upper stretches but the NPS has constructed bridges towards the lower end.

Indian Gap Trail, as it was locally known, connected the Tuckasegee River to Gatlinburg. It bisects the Great Smoky Mountains, crossing the crest at Indian Gap. Many intersecting trails and forks off the Indian Gap trail led to special destinations throughout the Great Smoky Mountains.

Directions: Park on the Clingmans Dome Road at the Indian Gap parking area/kiosk and walk the trail downhill to the Chimneytops parking area.

Disappearance

Many unforgettable events transpired as I bushwhacked up and down the Appalachian Mountains of Western North Carolina hunting and mapping trails and places. But the strangest and most grueling trip in my memory was when I was led to a sacred place by three Cherokee men by horseback and on foot into one of the wildest and most remote places in Great Smoky Mountains National Park.

A 58-year-old Cherokee man named John offered to take me to an ancient and sacred place, providing that I not reveal any information about its name or location. I agreed and he arranged for his cousin and friend to meet us with four horses. He said there was an old man-way to the place, so we saddled up and rode many miles before ascending a high mountain. John’s cousin dismounted several times along the way to examine medicinal and edible plants his grandfather had taught him. We rode on several miles as far as we were able, dismounted and tied our horses. The rest of our journey would be on foot.

Since I was traveling with John, I didn’t bother to bring my highly detailed topographic maps of the area. My GPS was prominently hanging from my pack strap and I wondered if my Cherokee friend had concerns about my GPS even though he did not forbid its use.

Since I was traveling with John, I didn’t bother to bring my highly detailed topographic maps of the area. My GPS was prominently hanging from my pack strap and I wondered if my Cherokee friend had concerns about my GPS even though he did not forbid its use.

We walked an old trail to the brow of the mountain and began to climb down the side slope. The faint path was royally overgrown with gnarled mountain laurel so thick that a rabbit would think twice before following. We crawled, climbed, slid, contorted, and inched our way down the mountain. I dared not let my friends get too far ahead.

After a thousand-foot drop in elevation in 2.6 miles, we finally approached our destination late that afternoon. We quietly observed the sacred destination. Now it was time to find our way home.

I knew then that I was in trouble if we expected to make it back to the horses before dark. An alternate route was determined and we began walking along a stream that skirted the mountain where our horses waited. The laurel was so dense that we ended up wading in the creek, on treacherously slippery rocks with our boots full of water. Frequent logjams forced us to circumvent them through the laurel.

About this time one of the strangest things that ever happened to me occurred. As I was walking beside the stream in an open, flat place, my feet went out from under me and I fell barely into the edge of a small pool of crystal clear water that was only three feet across and two feet deep, and maybe six feet long. I was grasping my GPS tightly in my left hand—which may or may not have gone underwater—but at that moment, I had the distinct impression that somebody snatched the GPS out of my hand. I quickly got on my knees to grab it, but it had disappeared. There was no place it could have gone. It just vanished. I checked the rocks in this tiny pool to see if it was trapped. I called to John and the three went down the banks for several hundred yards to see if it had floated away. There was no trace of it. I realized it was gone forever. We were racing against darkness and could not linger.

Now all I had for navigation was my backup compass and a map of Great Smoky Mountains National Park with an all but worthless scale of one mile per inch. The waypoint where our horses were waiting was gone. If needed, the GPS would have guided us, but getting out of the mountains before dark would depend now on the ancient navigational intuition of the Cherokees.

Tired and banged up, it was tough going with wet boots and soggy hiking socks. It was even tougher trying to keep up with three Cherokees who grew up walking and running these mountains. It was almost dark and I had already resigned myself to a cold, wet night in a space blanket by a fire. But just when it appeared to have become too dark to travel, John called from afar. We moved in increments after each whoop until we arrived at our beloved horses and rode off in the last light.

I have seen many things on this web of paths, but I was left with an eerie feeling over the inexplicable disappearance of my GPS. John believed the Little People took my GPS because it was not meant to be there. I’m not a superstitious person, but I have to concede: there are many things that happen in these mountains that cannot be explained.

The Ghost Dance

Buffalo (or Eastern bison) were trail builders wherever they went. From the time they arrived in the Southeast, they grazed the barrens or prairies of Tennessee and Kentucky, crossed the Appalachians visiting grassy balds and river plains, and wintered in the savannas and swamps of the Carolinas. Indians—and later, white hunters—followed these natural highways. Mountain passes were the most efficient places for the Cherokee to cross the mountains and the best places to hunt buffalo and other large game traveling to salt licks and swamps in the lowlands.

While few archaeological remains such as bones have been found, there are ample accounts and records that testify of buffalo found adjacent to the perimeter of the Carolina and Virginia highlands. Because of such a wide spectrum of elevation and geology, the Eastern Indian tribes contributed to the perpetuation of several grassy habitat types by using fire.

The buffalo was a favorite big game of the Cherokee, who used the flesh as food, the hides for blankets and bedding, and the long hair for spinning articles, including belts. The horn was prized for carving into needles, combs, and spoons.

One of the last records of buffalo in the mountains of Western North Carolina is the oral testimony of Chesquah, or Bird, who was born about 1773 and grew up in Buffalo Town in the Cheoah River, one of the most remote and last strongholds of traditional Cherokees.

Chesquah said that he remembered seeing large herds of buffalo in what is now the Robbinsville area, and that he played stickball at the site of present-day Knoxville when it was but old grassy fields. He stated that he had followed the last buffalo herd across Hooper Bald as it headed west.

An old trail leaves the flats of West Buffalo Creek and crosses King Meadows to Hooper Bald. From there a primary Cherokee trail followed the North River to the Tellico Plains, an area of fifteen or twenty square miles that was covered with rich grasses.

The extirpation of the last Eastern bison contributed to the Cherokee Ghost Dance movement that sprang up between 1811 and 1813, in which both the return of the buffalo and the disappearance of the white man were predicted.

About 1811, a half-Cherokee prophet named Charley traveled to north Georgia to proclaim his message: the deplorable state of the Indian, he said, was caused by the abandonment of pure traditions and the adoption of the ways and material culture of the white man. He told them that the mills, houses, spinning wheels, clothes, beds, flint and steel fire starters and domestic cats defiled the Indian. For this reason the buffalo, elk, deer, and hunting grounds had largely disappeared. If the Cherokee would believe, obey, paint themselves, dance, and return to the old ways, the game would return and the whites would disappear in a fierce storm of hailstones as large as hominy mortars. In order to be saved from the wrath of the Great Spirit, the Indians must take refuge in a sacred bald, now believed to be Clingmans Dome of the Great Smoky Mountains. Despite attempts by Major Ridge and others to persuade the attendants that Charley’s prediction was not credible, a pilgrimage ensued, and Cherokees were soon seen marching along the Valley River with packs on their backs as they headed for the Smoky Mountains. Some were persuaded by the Valley River residents to turn back, but others remained in the mountains until the determined day of restoration failed to occur.

Today, I believe the mountains are the poorer for the loss of the buffalo and other extirpated and extinct species. The memory of the buffalo lives on in the names of Cherokee ancestors and in the place names across North Carolina and surrounding states. There are Buffalo Creeks, Rivers, Fords, Mountains, Forks, Licks, Valleys, Ridges, Springs and Swamps.

I am thankful for the perseverance of those Cherokees and their few white allies who fought against the discriminatory policies of the early 1800s that would have extirpated the Cherokees from their ancestral homeland. Their story, history and cultural heritage enrich the lives of us all.