From monsoon rains to the norovirus, this year’s Appalachian Trail thru-hiking season was one for the records. The stories of struggle and success have swept across the Blue Ridge, from Springer Mountain, Ga., to Mount Katahdin in Maine. But while these sagas were still in the making, one hike in particular was setting a new record: the first thru-hike of the Great Eastern Trail.

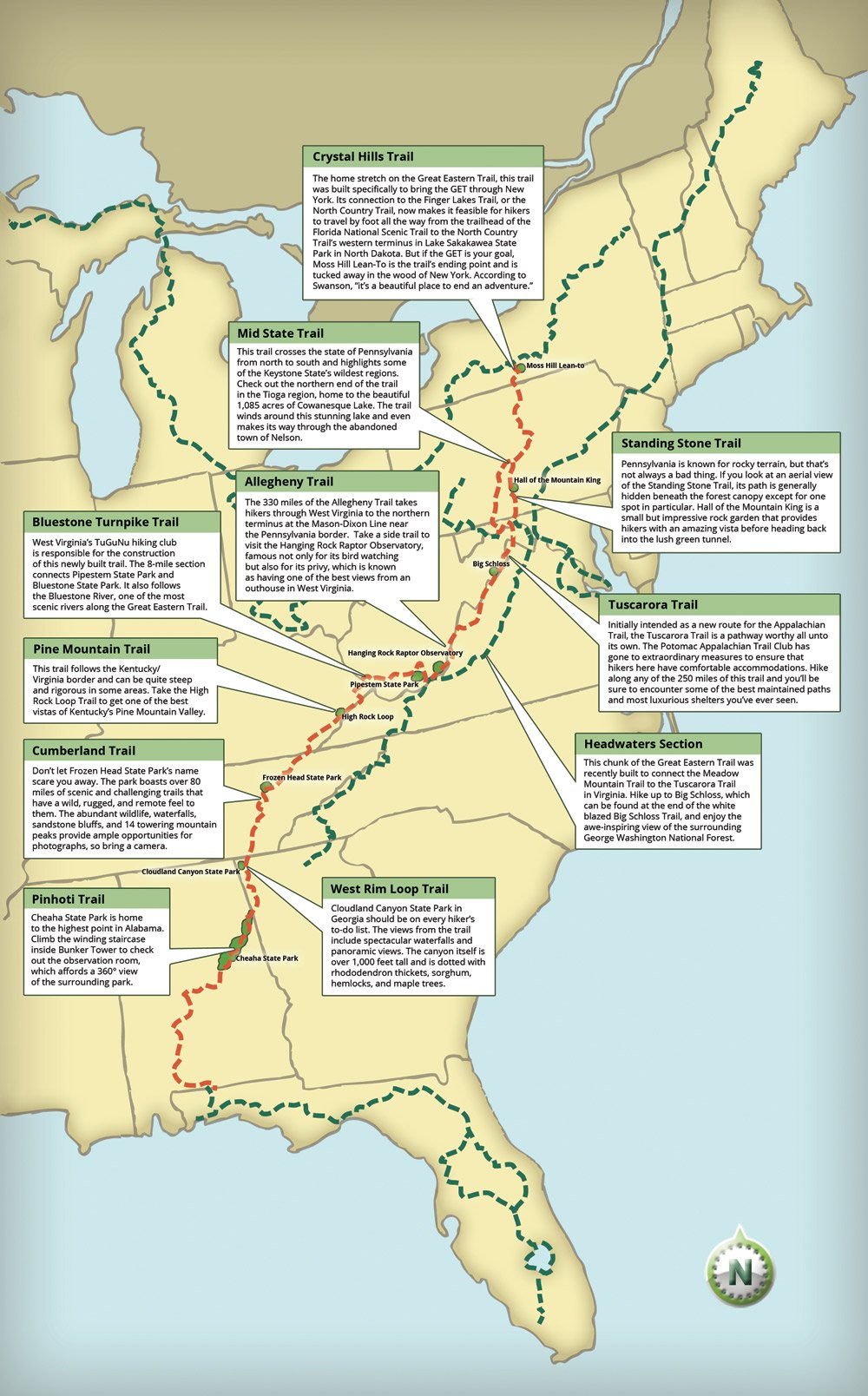

Meet Joanna Swanson and Bart Houck, or Someday and Hillbilly Bart if you encounter them on the trail. They are the first thru-hikers of the roughly 1,600-mile long Great Eastern Trail, which connects a series of preexisting trails and stretches from Flag Mountain, Ala. to the Finger Lakes of New York. With a lesser overall gain in elevation and a shorter length than the Appalachian Trail, the Great Eastern Trail rivals its Appalachian counterpart with a different set of challenges which, for Swanson and Houck, began even before they set foot on Alabama soil.

I said ‘Hell No’

Despite growing up in Willow River, Minn., Swanson was well acquainted with the opportunities for adventure on the East Coast. During two separate hikes in 2009 and 2010, Swanson successfully completed a southbound section hike of the Appalachian Trail. When she returned home, she realized those months on the trail had fostered a gnawing restlessness within her that could only be satisfied by embarking on another adventure.

“I was looking for a trail experience,” Swanson says. “I came across the AmeriCorps website and they were looking for an AmeriCorps Vista volunteer in Mullens, W.Va. working for the Great Eastern Trail. I’d never heard of it,” she says, but that fact didn’t seem to faze her. She applied, was accepted, and moved to West Virginia in November of 2011.

Mullens, W.Va., is home to just over 1,500 people including Houck, who was born and raised in the small coal-mining town. Houck always considered himself an outdoorsman, although he came to know West Virginia’s mountains and forests through a different lens than Swanson.

“I’ve always hunted,” Houck says, “or, I’ve always ‘hiked with a gun.’”

Swanson and Houck met through their involvement with the local TuGuNu Hiking Club, a relatively new group of outdoor enthusiasts who wanted to bring more than ATVs and hunters to West Virginia.

“One day I showed up at his house with bacon and a case of beer and he let me stay,” Swanson says, nudging Houck.

The idea to thru-hike the Great Eastern Trail did not occur to Swanson until she was nearly a year into her service with AmeriCorps. Her duties primarily involved building official miles of the trail in West Virginia which, when she arrived, were nonexistent. In July 2012, Swanson realized that West Virginia was the part of the Great Eastern Trail that was logistically the most difficult, but for her was the section she knew best.

“I knew it wasn’t a trail I wanted to do alone,” she says. “So, I asked Bart if he would come with me.”

“And I said ‘Hell no. You’re crazy,’” Houck says. “When I had done all the planning,” Swanson continues, “when I had all the resources, bought all the guidebooks, he decided that was a good time to reconsider.”

After nearly 10 months of planning and hundreds of hours of collaboration with the Great Eastern Trail’s board of directors, Swanson and Houck finally set out on their journey in January of 2013. Unlike either of the Appalachian Trail’s terminals, the trailhead for Flag Mountain, Ala., is not nearly as well-established, tucked away in a one-horse-town known as Weogufka (wa-guf-kah): population, 282. Houck’s brother drove the two to the trailhead, and though both Houck and Swanson came from humble hometowns, the Alabama backwoods proved to be a far cry from home.

“Along the way we stopped in this little town that had absolutely nothing but one convenience store,” Houck says. “We walked inside and asked the lady, ‘Can you tell us where Weogufka is?’ She said, ‘Weogufka? Honey, that’s way back in the sticks.’ I said, ‘Honey, we are in the sticks. How much stickier is it gonna get?’”

Fortunately, Swanson had arranged to meet up with two trail angels who would help them find their way to the Pinhoti Trail, the first built trail of the journey. These two hiking enthusiasts would prove to be the first of many supportive followers that Swanson and Houck would encounter during their five-month trek.

“Our experience really snowballed as we went along,” Swanson says. “In Alabama and Georgia, we were mostly flying under the radar.”

“But the further we went, the more legitimate we became and the more we decided that this trail is bigger than both of us,” Houck says. “We decided to slow our trip down and become ambassadors for the trail.”

Almost Dead in an Alabama Snowstorm

Although Swanson and Houck began their thru-hike in the middle of winter, the weather in the South remained relatively mild. As they approached the northern parts of Alabama though, the once-pleasant rain took a dangerous turn.

“It had been raining for days and everything we had was wet,” Houck says. “We had 13 miles to go in order to make it to Cheaha State Park. The further we went up, the more it started sleeting.”

Houck decided they should put on rain gear for some added protection, although by now he and Swanson were both completely soaked and still wearing shorts. They continued hiking, thinking the weather would break, but as their body temperatures continued to drop so too did any hopes of sunshine and clear skies.

“Then it started snowing,” says Houck. “Then it started really snowing. Then it started blowing snow. The blazes on the trees were covered. Thirteen miles doesn’t seem very far until you’re stopping at every tree.”

Despite their slow pace, Swanson and Houck had only one option and continued on, trudging through deep snowdrifts and squinting against the wind for any trace of a blaze. Houck periodically lost sight of Swanson and would wait for her to catch up before carrying on, but he remembers one time in particular when it took her longer than usual to make an appearance.

“I couldn’t wait long because I had to keep moving,” he says, so he walked back, hoping to find her a short distance behind. She was not close, however, and when Houck came upon her, she was nearly naked with her shirt stuck up above her head.

“I was kinda like the Tinman in the Wizard of Oz,” says Swanson, “except I was frozen solid. I couldn’t move.”

In an effort to replace her drenched clothes with warmer layers, Swanson says the freezing cold had quickly sapped any remnants of mobility. Her skin began to redden and chap from the icy air, and Houck knew that their situation was quickly worsening.

“I helped her get dressed and told her we had to keep moving,” he says. “We played mind games to keep our mental clarity.”

“I led us off the trail, downhill,” says Swanson.

“Twice,” reminds Houck, “but you never heard me complain.”

Finally, the two arrived at Cheaha State Park to find that the situation there was equally as dire: the park was closing and its employees were being sent to a nearby hotel to wait out the storm.

“I slapped my credit card down so fast,” Swanson says, “I didn’t care. I was just thankful there was still one room left.”

After shedding their soggy clothes and devouring a hot meal, Houck took to humor to relieve some of the tension.

“I turned to Jo and said, ‘You realize that you’re from Minnesota, you lived in Alaska, and you just about died in an Alabama snowstorm? That’s the only reason I kept you alive. Nobody would have believed me.’”

Although Swanson and Houck were not injured from their prolonged hike through the miserably wet and bitterly cold, the two decided to take a zero day to regroup and relax.

“You know what we did on our day off?” Houck says. “We went for a hike.”

Wash, Rinse, Repeat

“One of the biggest challenges was putting up with each other,” Swanson says.

Unlike the social scene that accompanies the thousands of Appalachian Trail hikers, Swanson and Houck were alone on their thru-hike of the Great Eastern Trail.

“It’s a lot to handle, being with one person for five months,” says Swanson.

“The monotony of everyday living is hard, too,” says Houck. “You pack up your stuff in the morning, hike for 10 hours, unpack…”

“Wash, rinse, repeat,” says Swanson.

Although both have extensive experience living with and off the land, they opted for the quick and easy when it came to backcountry meals.

“Who was the cook? Let’s see, Food Lion, StarKist, Peter Pan,” Houck says. “At first I had made a beer can burner that was really lightweight, but it didn’t work very well in the wind. I abandoned that idea pretty quick.”

With cool weather on their side, Swanson and Houck packed everything from cheese to meat. Because of their frequent road walks and town crossings, the two were resupplying every three to four days.

“My luxury item was beer,” Houck says. “Cheap beer.”

By the time Swanson and Houck arrived near the Great Eastern Trail’s terminus in Finger Lakes, N.Y., they had grown from two individuals with a common interest to a well-oiled hiking machine. The thru-hiking duo had acquired a number of fans through their GET Hiking blog, which they updated throughout their trip with photographs and thoughts from the trail. All eyes were on Someday and Hillbilly Bart as they embarked on the final miles of their hike.

“We knew there would be some friends and different media outlets who would join us for the last mile of the hike,” says Swanson. “On the last day, we hiked about five miles before we came to the road crossing where everyone was waiting.”

“We sat there in the woods alone and listened to car doors slam,” says Houck. “We ate our lunch alone, which was very fitting.”

“We needed that time before sharing it with other people,” says Swanson.

Radio stations, television reporters, friends, and trail volunteers joined Swanson and Houck at the endpoint, a shelter in New York known as the Moss Hill Lean-To. After an hour of socializing and taking pictures, the two were left alone again for their final night in the woods.

“We could have gone somewhere to take a shower and everything, but we decided no, the last night on the trail was going to be spent on the trail,” says Houck.

Bringing Back the Future

Being the first to accomplish something is never an easy task, especially when it involves being the trailblazers for a trail that’s not even technically complete. According to Swanson, the Great Eastern Trail is currently over 70% finished with fewer miles of road walking than what Earl Shaffer encountered when he first hiked the Appalachian Trail.

Swanson and Houck agree that the real challenge of the trail will be getting it finished, particularly in West Virginia. Mullens, Houck’s hometown, is located in Wyoming County and is conveniently the halfway point along the trail. Though the hiking community in Wyoming County is growing, Swanson and Houck say it’s not enough to get the Great Eastern Trail established in its entirety through the wild and wonderful state.

“We need an organization that can make deals with landowners and represent the cause,” says Swanson. “One new hiking club is not old enough, strong enough, to do something like that.”

Pocahontas Land Corporation, a company that manages natural resource properties, owns most of the land in Wyoming County but has shown support of outdoor recreation through its interactions with the Hatfield-McCoy ATV Trail system.

“The Hatfield-McCoy Trail Authority is a pretty big organization with a very strong board of directors and strong leadership and a very good insurance policy,” says Swanson, “and that is what the hiking community is lacking. We don’t have the funds to do it.”

“We have to garner a state authority to serve as a go-between the hiking club and the Pocahontas Land Corporation,” says Houck. “Their concerns need to be on the table as well.”

Though the development of full-fledged state parks seems highly unrealistic, Swanson says that many trails along the Great Eastern Trail are, in and of themselves, considered linear state parks.

“That’s not a foreign concept,” she says. “We’re trying to work with the Wyoming County Commission to see if we can get a pilot section of trail built where there’s a gap. West Virginia will continue to be the hardest state logistically for at least the next decade, but that doesn’t make it impossible. It can be done.”

West Virginia has had a long history of economic success fueled by natural resources, but according to Houck, its coal-mining towns are withering and their economies struggling to stay afloat.

“If you want to create an environment of economic growth, you can’t depend on something that’s going to die,” he says. “Beauty in the mountains is never going to die unless you outright kill it. I think the natural beauty of trails and recreation can bring West Virginia into the future.”

The future for West Virginia’s acceptance of the trail seems positive thus far. Pocahontas Land Corporation has expressed interest in opening the dialogue between hikers and landowners. Should the Great Eastern Trail be officially established in West Virginia, its route would go through five different communities. Four of those five communities have already signed a town agreement in support of the trail.

“This trail has the potential to bring in so many tourism dollars,” says Swanson.

“If West Virginia lets this go, it will be a very big disappointment,” Houck says. “That’s one of the reasons I hiked this: to show that it can be done.”

The board of directors for the Great Eastern Trail has backup plans to reroute the trail through Virginia, bypassing West Virginia entirely save for a small section near the northern end. This, says Swanson, would be a great setback, since one thing that makes the Great Eastern Trail different from the Appalachian Trail is its route through the Mountain State.

“There’s such a great hiking culture in the East that another long trail should be welcomed by everyone,” she says. “We’re not trying to take away the glory of the A.T. It’s its own unique trail.”

“I think the Great Eastern Trail is also different in that it links a lot of trails that already exist,” says Houck. “They are smaller in and of themselves, but linked together they make a ‘great’ trail.”

Swanson and Houck say the overall highlights during their experience was not any particular view or wildlife sighting; it was the overwhelming support they received from the various trail volunteers, club presidents, and trail angels.

“These people are active all the time,” says Houck. “They aren’t just a name in a pamphlet.”

What words of wisdom and knowledge can Someday and Hillbilly Bart provide?

“Know your limits,” says Houck. “Start out small. Plan, but be flexible. You can create and accomplish goals so easily out there. Each day is a goal, each state is a goal.”

Houck said the best part of the journey was waking up everyday to go hiking.

“It’s also really cool to be yourself,” he says. “To be able to enjoy yourself by yourself is really important.”

Swanson agrees. “I think people have gotten disconnected from their natural world,” says Swanson, “so it was nice to feel the miles and know the miles.”

Hillbilly Bart & Someday

Someday: I got my trail name on the A.T. I was in New Hampshire hiking southbound and I still hadn’t received a trail name. I was complaining to the guy at the hostel saying, “someday I’ll climb up these mountains without huffing and puffing, someday I’ll do this, someday I’ll do that…” I had a whole list. He looked at me and said, ‘I think you have your trail name.’

Hillbilly Bart: I took the alternative route and named myself. It seemed appropriate. Everyone at home calls me that. It was good too, even to bust a lot of stereotypes about what a hillbilly is.

What is its geographic coverage?

The 1,600-mile trail passes through nine states: Alabama, Georgia, Tennessee, Kentucky, West Virginia, Virginia, Maryland, Pennsylvania, and New York.

Which preexisting trails are connected to form the GET?

Alabama-Georgia Pinhoti Trail, Benton MacKaye Trail, Cumberland Trail, Pine Mountain Trail, Allegheny Trail, Bluestone Turnpike Trail, Mary Draper Ingles Trail, Tuscarora Trail, Headwaters Section, Green Ridge State Forest, Standing Stone Trail, Mid State Trail, Crystal Hills Trail

How long will it take to hike?

4 to 6 months

Who thought of the idea?

Earl Shaffer, the first Appalachian Trail thru-hiker, wrote of the idea in a letter to his brother, circa 1948. Originally referred to as the Western Appalachian Alternative, the trail finally received its rightful name in 2007 when the Great Eastern Trail Association was formed.

Is there a guidebook?

Yes, but it is a work in progress. Consult greateasterntrail.net or Swanson and Houck’s blog, GEThiking.net, for more information.