Appalachian Ecotherapy and Why We Need it Now

Click here to read the whole article

False Promises and Re-thinking ‘Normal’

When Plato looked at the night sky, his heart brimmed with optimism that human curiosity would “compel the soul to look upward and lead us from this world to another.” A lofty notion perhaps, but not inappropriate. The universe is indeed lofty and our desire to understand how it all works has set us apart as a unique species. From spears to aqueducts to the light bulb, innovation carved footholds into life’s learning curve with barely a look back. Implied, of course, is the proverbial peak of utopia.

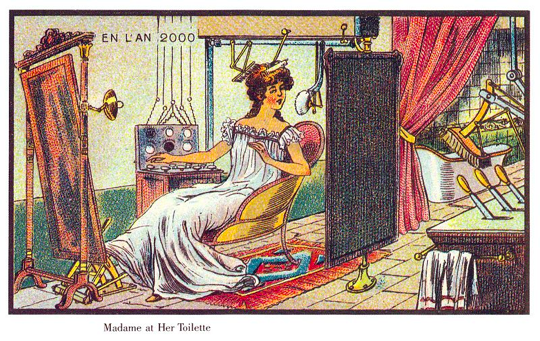

On the heels of the Industrial Revolution, economist John Maynard Keynes predicted an idyllic future — within 100 years, the human race would no longer need to worry about bringing home the bacon, but instead on how to “pluck the hour and the day virtuously and well.” In 1965, TIME Magazine heralded the rise of computers as the dawn of a “modern Hellenic age.” Like the ancient Greeks, we would have time to “cultivate [our] minds and improve [our] environment while slaves did all the labor.” In this case, the slaves would be technology.

The Internet Age made a lot of shiny promises: accessible information would make us smarter, digital tools would make us more organized, online communication would keep us more connected. We certainly bought in to the hype. Americans now spend more than eleven hours per day staring at computers, phones, tablets, and televisions. So how is this working out? To put it short, it’s not.

Our physical health is abysmal compared to other industrialized nations. The stereotype of the fat American isn’t a stereotype at all. On average we’re sedentary for twelve hours per day and 40% of the population is obese, contributing to increasing diagnoses of diabetes, heart disease, and myriad other health concerns. But how can you blame anyone in a world where interstates have mile markers to the nearest Taco Bell? There is such an implication of urgency in every part of our lives that you can forget about cooking, exercising, or even sitting down for a meal. There’s so little time we actually have to abbreviate the word “drive-thru.”

Psychological well-being also appears to be suffering, with an estimated 1 in 4 adults affected by mental illness and 40% of Americans feeling more anxious than they did last year. Most of the population reports being lonely and isolated with only one friend on average, and one in four have none at all. Even with society’s tolerance of casual sex at an all-time high, young adults are actually having less sex than previous generations. “Netflix and chill” was once tongue-in-cheek and cheeky — now it’s just literal and sad.

But much more devastating is that today’s children, the first generation to grow up completely in the fluorescent glow of the ubiquitous smartphone, are paying the highest price. Even the youngest millennials remember a time when they’d be kicked off the computer and ushered into the backyard to play so Mom could get off dial-up and use the phone. But Gen Z (born mid-nineties to mid-2000s) don’t.

Researchers are concerned with how much of a nosedive this generation’s mental health has taken. Gen Z is most likely to report poor mental health and is the only generation with less than half of its population reporting excellent or very good mental health. Half of them will experience a diagnosable psychological disorder before age 18, the most common being anxiety, ADHD, bipolar disorder, and depression.

This is not a country of flourishing people.

Unfortunately, scientific research is much slower than the evolution of technology, and it’s hard to say exactly why these statistics look the way they do. And just like most human behavior, it’s highly unlikely that only one variable is at play. It is the curse of every social scientist. But the data are starting to suggest that increased screen-time may be linked to all of these problems. Americans are overstimulated, socially disconnected, and increasingly unhappy, with technology partially to blame. It’s a far cry from the hopes of Plato, Keynes, and TIME Magazine. Quite contrary to their predictions, it seems we have become slaves to technology rather than the other way around.

Though researchers still debate the inherent harm of screens, it’s impossible to get around the fact that so much time spent in front of them means that something else (or perhaps everything else) has got to give. What time do we have left to care for our children and homes, to get a good night’s sleep, to enjoy hobbies, to spend time with our friends, or to engage in more physical activity than the walk between the cubicle and the coffee maker?

Time available for life lived beyond pixels is diminishing. So much for “plucking the hour” — we don’t have any left to pluck.

Kittens on the Carousel

Ever seen those flyers posted around college campuses recruiting experimental guinea pigs in exchange for cash or class credit? Well, once upon a time as a University of Virginia undergraduate, I was the one with the clipboard taking notes.

The tests and protocols were designed by PhD candidates under the mentorship of Dennis Proffitt — professor, researcher, and Director of the Undergraduate Degree Program in Cognitive Science. He and his graduate students were interested in how we perceive the world and ourselves within it. I learned that our reality is made of a whole lot more than the images that reach the retina. The motto of the Perception Lab probably should have been “there’s more than meets the eye,” because what meets the eye is the tip of a very large iceberg.

In the first experiment I ever ran, I asked students to estimate the angle of a hill while looking at it from its base. Unless they had prior experience in construction, I learned that humans are bad at this game. Participants consistently guessed angles more than three times as steep as reality. But what was more surprising was that I could make them believe the hill was even steeper without suggesting a thing. I just asked them to put on a backpack.

The backpacks were filled with weights — specifically 10% of each participant’s body weight. Participants in the experimental backpack group believed the hills to be significantly steeper than those in the control group. Why? Because with a heavy load on your shoulders, a hill looks like a real pain the ass to climb. Keep in mind I never told participants they would be expected to climb the hill. But that’s irrelevant. Even if your brain is not consciously aware of what’s going on, it’s constantly making its best educated guesses about the environment in anticipation of how you may need to interact with it.

But what happens when you have a limited experience of interacting with your environment? Say, perhaps because like the average American, you spend 90% of your time indoors? How does your brain deal with an atrophied understanding of what your body can and cannot accomplish?

—

“Remember the Kitten and Carousel experiment?” Professor Proffitt asked me.

When I began writing this article, my former psychology professor was one of the first people I sought out for perspective. There are few I respect more for their intelligence and scientific integrity, and this was an area of his expertise. Nature is our environment, after all. I’d asked if he’d answer some questions about nature and human perception and somehow we had gotten to talking about felines and amusement park rides.

“It’s been a few years,” I admitted. Professor Proffitt’s face is famously inscrutable, but I hoped I hadn’t disappointed him by forgetting one of his lectures back in his introductory college course.

“Well, there’s two kittens on a carousel,” he began without missing a beat, seamlessly transitioning into his natural teaching mode. He scratched a rough sketch on a notepad between us on the desk. “One has control over locomotion and can move around, and the other gets moved around and can only observe.”

Later I Googled this experiment for clarification to find it considerably less adorable than it sounds. In the 1960s, scientists chose pairs of newborn kittens from the same litter and raised them in darkness, only exposing them to light while inside this contraption.

The control group kitten is placed in a harness with the agency to walk around in a circle. The other kitten is yoked to him on the same turntable, spinning at the behest of his brother. The second kitten is unable to do anything other than observe the room go round and round. After a few weeks, they allowed the kittens to freely explore a lighted room. The two groups of kittens took to this test quite differently.

“Both can see just fine in terms of measuring their eyesight. But the cat that has had control behaves normally. The other cat that did not have control acts like it’s functionally blind. It walks off of tables, into walls. It doesn’t understand its experience,” Professor Proffitt explains. Because the kittens in the experimental group had no way to understand how their visual perceptions were related to their own actions, their brains could not correctly interpret what their bodies were able to do. “Action allows you to see the world in terms of what you can do. What we see in the world are opportunities for action.”

I was beginning to connect a few dots. The less we actively interact with the physical world and the more we passively observe, the closer we become to the kitten in the sidecar. With electronic media now dominating our lives, we have drifted far away from the lifestyle we evolved for. Living in the virtual world does not provide many opportunities for action. Maybe, in a way, we’ve become functionally blind.

Prophylactic and Panacea

If you’re still with me, I admire your patience because no one wants to hear how bleak and crappy and doomed things are. It’s not fun and it’s not a new idea. Even one of the ecotherapists I interviewed and came to deeply respect encouraged me not to focus on the negatives because scaring people is often counterproductive. I’m certainly not trying to fear-monger and I hope these articles bring more hope than fear.

However, I think it’s important to recognize that something is awry in our society, and the numbers are revealing. With how quickly technology has changed in recent decades, there are already many people on Earth who have absolutely zero memory of a time when the Internet and screens were not omnipresent. In the not-so-distant future, no one will have a basis of comparison in their own memory to conceive of a world without them. Even older adults who grew up with payphones are struggling to just remember what it used to be like.

Children of today negatively impacted by this culture may grow up to believe something is wrong with them, and not the social norms that they’ve known their entire lives. Spending half of waking life with your face in a screen is normal. Sitting and being inactive for literally half of an entire day is normal. With such significant consequences for well-being, it’s urgent we bring awareness to the fact that normal should not be conflated with good or even okay.

Consider Mr. Blobby. Voted the most hideous species and adopted as the mascot of the Ugly Animal Preservation Society, he (or she) looks like the love child of Nintendo’s Kirby, a fish, and “Kilroy was here.” Mr. Blobby was trawled from an ocean floor over 2000 feet below sea level. Because it evolved under so much (literal) pressure, it uses water as structural support. When pulled to the surface, the change in water pressure causes its body to become distorted, resulting in a photo that spawned the meme: “Go home evolution, you’re drunk.”

But evolution is not drunk. Evolution means adaptation through years of natural selection, something the blobfish obviously accomplished, or else it wouldn’t exist. But we pulled an animal literally half a mile in altitude from the habitat in which it evolved under thousands of pounds of pressure and millions of years. When your body is engineered to operate within a specific environment, things don’t always translate so well when you get yanked out of it. In the face of an unadaptable environmental change, it experienced a complete system failure. No wonder it looks so monumentally busted.

Would it be too ham-fisted to ask: Are we in danger of becoming Mr. Blobby?

Perhaps, but there it is.

—

Still, in the course of my interviews, I’ve been reminded more than once by people much smarter than I that technology is ultimately a good thing for humanity. I’ll admit that the above-mentioned statistics regarding the state of America didn’t exactly fill me with optimism, but my sources rightly called me out. Without information technology, you wouldn’t be reading this article right now. My voice (and everyone’s) would be limited to the people within earshot of a soapbox, and your knowledge would be limited by your proximity to one.

And perhaps most importantly, when it comes to technology, once you pop, the fun don’t stop. There are no take-backs for innovation, no putting the toothpaste back in the tube. The singular option is adaptation. One of the ecotherapists I interviewed, Beverley Ingram, insisted she wasn’t anti-technology because it’s here to stay. “Right now, technology is not being used well,” she admitted. “We have to get smart about how these things are taking advantage of our brain, dopamine, and serotonin. It’s like we’re a little kid in a candy shop, throwing up because we binged on all the sweets.”

Our brains reward us with hits of dopamine for every piece of information we consume, same as when we consume a piece of candy. Those hits of dopamine can become addictive and the desire for more can trump the desire to do anything else. Physical inactivity, social disconnection, and mental illness may all be symptoms of the same malady: a little bit too much time glued to a screen. “We can learn not to binge on sweets,” asserted Ingram. “And we can learn to find a balance.”

It seems we need a yin to the yang, something to bring equilibrium to a world increasingly dominated by the manmade, by the virtual, and by the left-brain. Returning to a state of balance could solve a whole host of problems, and it may be easier to achieve than one might think. There is a remedy that is both a powerful preventative and cure to the negative impacts of technology and urbanization. A healer and a protector.

It’s something that makes people more caring and reduces crime, something that decreases anxiety and promotes higher self-esteem, something that calms the nervous system and improves performance on cognitive tests. Something that relieves pain, improves immunity, and treats anxiety, depression, and ADHD with little risk of adverse side effects. Something that promotes exercise, mindfulness, play, and socialization. Something that kills a lot of birds with one stone.

And given the inaccessibility of quality healthcare in America, it’s crucially important for people to know about something so inexpensive, so accessible, so customizable, and so diverse in modalities. No matter who you are reading this article, it is something from which you can benefit.

That something is nature.

—

According to the research conducted by ecopsychologist Chad Chalquist, “disconnection from the natural world in which we evolved produces a variety of psychological symptoms that include anxiety, frustration, and depression” and contribute to a “pathological sense of inner deadness or alienation from self, others, and the world.”

Thankfully, it is never too late for reconnection. Science shows that reconnecting with nature (through gardens, animals, nature walks, nature brought indoors, and more) can improve health, self-esteem, foster social connection, and bring joy. Engaging nature gives us a second chance to see clearly. Taking those opportunities for action teaches us what it means to be a living thing on this Earth, giving confidence and clarity about who we are and our place among the chaos.

We may never realize the lessons we’ve internalized, and perception is kind of funny like that. But if something as simple and small as a backpack can change how steep you view the grade of a hill, then surely the act of actually climbing the hill could change your concept of yourself. And redeveloping a relationship with the natural world could change everything.