It’s just starting to snow as Rick Shortt and I hike into the clouds, climbing an old road bed to the pinnacle of Middle Knob, a 4,208-foot peak of Clinch Mountain in Southwest Virginia. On a clear day, Shortt says there’s an incredible view from a dilapidated fire tower on Middle Knob’s peak, but considering the soup we’re hiking through, the view will likely be a bust. It’s colder than either of us expected, so we’re not dressed for the sudden shift in the weather, but since we’re moving at a pretty quick clip, we’re soon sweating. The dude can hike. I’ve jogged at slower paces than we’re currently hiking, which makes me wonder how fast this guy would be moving if he hadn’t just had a hole cut out of his gut. He’s two weeks out of a hernia surgery, and this is Shortt’s shakedown hike to see if he can get back to the business at hand: the business of peak bagging.

“We call really bad weather ‘full conditions,’ as in F-O-O-L,” Shortt says as the snow transitions to a cold rain. He’s hiked in “fool” conditions before. He’s post-holed through hip-deep snow to bag relatively inconsequential peaks. He’s pushed through head-high stinging nettles. He has crawled for a mile on his belly through rhododendron, all in his 20-year-long pursuit of the highest patches of dirt and rock in the Southern Appalachians and beyond.

In the world of peak bagging, a hiking subculture where hardcore hikers obsess over lists of mountains grouped by characteristics, Rick Shortt could be the most obsessive of them all. The 46-year-old Wytheville native manages a print shop four days a week and typically spends his other three days trekking Southern mountains. By his own admission, he has no other hobbies, giving up the fishing and hunting of his youth as soon as he discovered hiking.

“If I’m not climbing a peak, I’m on the computer researching a peak to climb,” Shortt says.

The man has essentially arranged his life around peak bagging, living in Wytheville because it’s a crossroads of I-81 and I-77. “What I like most about Wytheville is that it’s easy to get other places from here,” Shortt says. “It’s three hours from Shenandoah National Park and three hours from Great Smoky Mountains National Park, and 30 miles from Mount Rogers. Wytheville is convenient, that’s all.”

The man has essentially arranged his life around peak bagging, living in Wytheville because it’s a crossroads of I-81 and I-77. “What I like most about Wytheville is that it’s easy to get other places from here,” Shortt says. “It’s three hours from Shenandoah National Park and three hours from Great Smoky Mountains National Park, and 30 miles from Mount Rogers. Wytheville is convenient, that’s all.”

He’s dressed straight out of a hiking catalogue. Gaiters, zip-off shorts, vest, GPS strapped to his shoulder, trekking poles in his hands. He is a self-professed hiking geek, with tinted specs and a graying goatee. Honestly, he looks more like a manager at a print shop than a hardened peak bagger, but looks can be deceiving.

“He’s perhaps the most hardcore peak bagger in all of the Southeast,” says Peter Barr, author of a soon-to-be-released book of climbing the South’s 5,000-foot-tall mountains. “It would take me 10 pages to list all of his feats and peak lists he’s completed.”

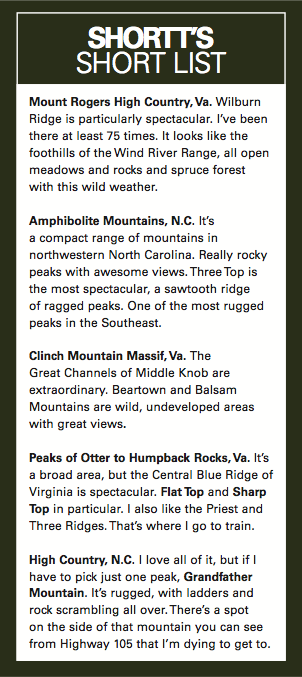

Along with his hiking partner Shane Ashby, Shortt was the first person to touch the summit of all 100 4,000-foot peaks in Virginia. He was the second person to climb all of the Southeastern Finest 50 (the 50 most prominent peaks from West Virginia to Georgia). He’s four peaks away from bagging all of the Southern Sixers (6,000-foot peaks), and halfway through the massive list of Southern Fivers (5,000-foot peaks). In total, Shortt has touched the top of 1,180 peaks in 20 years (yes, he’s counting), traveling all over the country (he’s bagged 25 of the 50 state high points), but doing most of his work in Virginia (358 peaks bagged) and North Carolina (158 peaks bagged), where some of the South’s tallest and most rugged mountains reside.

According to Shortt, peak bagging in the South is an odd mix of civilized mountains with paved road access and remote knobs without even a hint of a trail.

“Short Mountain in Russell County was one of the worst. We were in head-high stinging nettles, falling face first,” Shortt says. “But I’ll take stinging nettles over briars any day.”

Considering the drama of some of Shortt’s other conquests, the three-mile road walk to the top of Middle Knob isn’t much of a challenge, even just two weeks after his hernia surgery. But the summit is spectacular, and one of Shortt’s favorite mountains. The fog’s so thick when we reach the rocky summit that we can barely see the steel tower 100 yards away, but the real gem of Middle Knob is an acre of eroded passageways between big blocks of 40-foot high sandstone boulders called the Great Channels. The snow has picked up again by the time we drop into the first channel, slipping between two smooth walls of sandstone covered in thin layers of moss. Some of the channels are as wide as a car, while others are too narrow to squeeze into. It’s like caving without a roof.

Shortt had no idea these natural channels were here until he started ticking off Virginia’s tallest mountains. Shortt compiled a list of Virginia’s 100 4,000-foot peaks using data from the online peak-bagger clearinghouse listsofjohn.com, and started knocking off peaks, using a yellow highlighter to cross off each mountain he climbed from his master list. Shortt and Ashby finished the list in May.

“There were a few we weren’t sure we’d be able to get because of access. There’s so much private property in the South, it makes peak bagging interesting,” Shortt says as we move through the narrow channels, the snow falling in big flakes now. “But I spend a lot of time asking permission from landowners. Some of the mountains on the list are spectacular. Some are hard to reach. Some are in some guy’s backyard. Some are crappy. We had a lot of gnarly bushwhacks through briars that led to mountaintops with nothing but more briars.”

Peak bagging can be a frustrating process that might leave many of us wondering about the greater point of the pursuit, but for Shortt and others like him, the list is everything. Shortt has computer printouts of 4,000-foot peaks, state high points, county high points, 100 steepest peaks, peaks with 1,000-foot prominence, the 100 most isolated peaks in a given state…the potential lists can be endless. It can feel very Sisyphean, but that’s part of the appeal for Shortt.

“I’ve thought about moving out West, but there’s still a lot left to find in the Southeast,” Shortt says.

Ultimately, it’s curiosity that drives Shortt to devote every moment of free time to the art of pursuing the next lofty peak.

“You see a lot of places you never would’ve bothered to go to otherwise. I’ve been to some spectacular places I never would’ve considered visiting if they weren’t on a list. Middle Knob is one of them.”

Now that Shortt has knocked off the 4000-foot peaks of Virginia, he has a new list on his mind: the South’s 100 Steepest Peaks. He has the mountains broken down into a few different categories (steepest peaks within the last 100 meters of the summit, peaks with the steepest face) but he’s most interested in the steepest overall peaks. He used data on listsofjohn.com to figure out the angle of each mountain’s summit cone to surmise each mountain’s average angle of ascension. The overall steepest mountain in the South, according to Shortt’s data, is Table Rock, in North Carolina’s High Country, which has an overall grade of 25.44 percent as you approach its summit. It may sound like an arbitrary way to rank a mountain, but Shortt has a theory.

“I like big views,” Shortt says. “My theory is that because these mountains are so steep, they’re bound to have more cliffs and more overlooks. They’re bound to be more interesting.”

For the most part, Shortt has no idea what he’ll find. He’s halfway through the list already, but there are still 50 peaks left for Shortt to discover. He’s committed to rolling the dice on each of them. They could end up like Crabtree Bald, an open mountaintop meadow in North Carolina’s Balsam Mountains that’s similar to the Roan Highlands, “but without all the people.” Or, they could be like the South Mountains near Charlotte, where on one peak, Shortt had to climb through knee-high poison ivy for two miles to reach a non-distinct peak.

“Either way, I’m happy,” Shortt says. “There are days when I question my sanity, but I’ve never had a moment in the mountains when I wished I was at home watching football.”

We climb out of the channels and make our way beneath the fire tower, ready to start the three-mile hike back down to the warm car, but before we start dropping elevation, Shortt stops. “May as well hit the true summit while we’re here,” he says, scrambling a little ways to a small, rocky knob that sticks out just a bit higher than the other rocky knobs surrounding it. Shortt taps it with his foot, just to make it official.