A $1 billion fund could help heal scarred landscapes left behind by a century of mining—and help thousands of miners breathe easier. So far, though, the country’s most powerful Senator—Kentucky’s own Mitch McConnell—has not moved it forward.

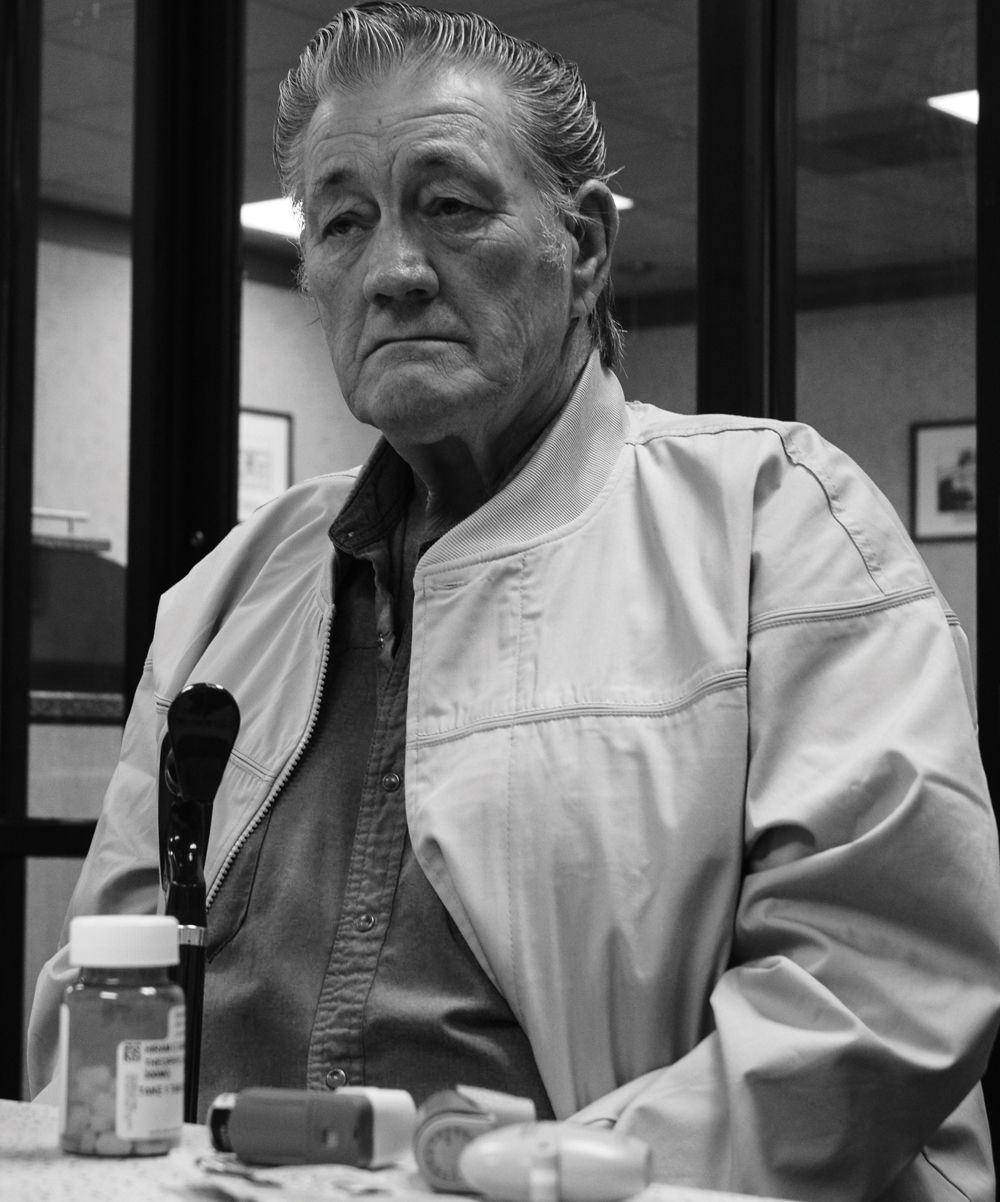

Clinton Sanders can never gulp quite enough air.

At night, he is tethered to an oxygen machine. And his constant daytime companion is a small, blue zippered case packed with an array of inhalers and other medicines doctors have prescribed to open passageways to his darkened, shriveled lungs.

The soft-spoken 79-year-old, who spent 27 years mining coal near his hometown of Ashcamp, was diagnosed with black lung disease in 2010. And like the thousands of other miners, young and old, slowly suffocating from an incurable disease that has reached epidemic proportions in the region, the great-grandfather of five never knows if his next breath might be his last.

He survived a bout with pneumonia last April and a quintuple bypass heart surgery more than a decade ago.

“I’m an outdoor person, and I used to do a lot of hunting and fishing, but I haven’t been able to do that anymore,” he says, leaning on his cane. “I cannot walk very far at all because I get too winded.”

A recent alarming leap in black lung—attributed to blasting through thicker rock in search of thinning coal seams—has galvanized a scrappy coalition in Kentucky and other Appalachian states intent on forcing Congress to lend more than lip service to the scarred bodies and landscapes left behind by more than a century of mining.

Ironically, the man with the wherewithal to make the coalition-backed $1 billion RECLAIM Act a priority in Washington, D.C. is Republican Mitch McConnell—a fellow Kentuckian and the powerful agenda-setting Senate majority leader. But Sanders and others don’t think he’s listening.

Won’t Cost taxpayers a dime

RECLAIM is short for this mouthful: the Revitalizing the Economy of Coal Communities by Leveraging Local Activities and Investing More Act. Versions of it are now on hold in both chambers of a mostly paralyzed Congress.

To the scores of miners and their families, RECLAIM is an antidote for people left behind by a coal economy that has collapsed as the country transitions to cleaner and cheaper energy from solar, wind and natural gas. Part of the legislation’s appeal is that the money is readily available.

Since 1977, Congress has required coal companies to pay into the federal Abandoned Mine Lands (AML) Fund for each ton they mined. The fund was designed to address pre-1977 abandoned minelands that were ignored or inadequately restored.

The $1 billion would be distributed over five years among coal states to spur community growth by transforming abandoned mines into agriculture, renewable energy, industrial, and tourism enterprises.

Fixing broken land is just one of the coalition’s goals. In tandem, participants also want to ensure that miners crippled with black lung aren’t dismissed as collateral damage.

They want coal operators to continue paying a higher excise tax per ton mined into the Black Lung Disability Trust Fund, a separate 1977 federal mandate. The safety net, designed to provide financial aid and healthcare to miners orphaned by bankrupt coal companies, is in danger of becoming insolvent.

Last year, Congress sliced taxes in half on underground and surface-mined coal. Those cuts would jeopardize payments to ill miners and cause the fund’s debt to rise from its current $4 billion to $15.4 billion by 2050, according to a Government Accountability Office report.

At least 4,000 Kentucky families are among the roughly 25,000 families nationwide that count on the fund’s benefits, according to the Appalachian Citizens’ Law Center.

“What’s unfolding across Appalachia right now is a national disgrace,” says Wes Addington, an attorney with the nonprofit’s Whitesburg office. “Pairing legislation that protects the trust fund with the RECLAIM Act is a clear solution for struggling coal miners and their communities.”

Where is McConnell?

The RECLAIM Act bill has lingered since 2016 without advancing under Republican leadership. What frustrates miners, to some degree, is why Kentucky’s own Mitch McConnell—the Senate Majority Leader—has allowed the RECLAIM bill to sit idle.

They are fully aware that the fossil fuel companies who have McConnell’s ear and fund his campaigns oppose the legislation, claiming it will only add to their financial duress.

Retired miner Jimmy Moore—one of Sanders’ neighbors in Pike County—is just one of dozens in the coalition who carpools regularly to the nation’s capital to ask his lawmakers to pass the RECLAIM package.

“I thank God I am able to go to Washington and speak for my fellow miners because most of them are too sick to go.”

-Retired miner Jimmy Moore

“It felt like we blowed a bunch of hot air out and it just vanished like a vapor,” Moore, 73, says about a fall meeting with McConnell’s staff in his Washington, D.C. office. “They probably laughed at us when we left.

“I guess I shouldn’t be surprised. Nobody can say one thing he has done for eastern Kentucky.”

Moore, a miner for 20 years, has advanced from treasurer to president of the tiny but nimble Letcher County chapter of the Black Lung Association, which advocates for miners in coal country. Black lung killed the elder Moore’s father and stepfather.

Coal companies should be preventing black lung, Moore says, and at the very least protecting sickened miners by caring for them properly.

And that effort should dovetail with reinventing job opportunities for upcoming generations of a labor force that was counted on for decades to perform back-breaking work required to harvest an energy source that powered the country’s industry, military, and electrification projects for decades.

“I thank God I am able to go to Washington and speak for my fellow miners because most of them are too sick to go,” Moore says. “I’m happy to represent them.”

Lately, Moore and his colleagues have felt like political pawns. Promised help is rarely delivered.

Retired miner Donnie Bryant, 66, emphasizes that he and his co-workers took pride in their jobs. His father died of black lung at age 62 and Bryant was diagnosed in 2011 after two dozen years in the mines. Poor breathing has caused hypertension and weakened his heart’s pumping mechanisms.

“You still live but you’re punished,” he says. “Even on oxygen, I am starved to death for air.”

Bryant’s circulation is so poor that he fears both of his legs will have to be amputated.

“Most younger people have to leave this area to get jobs,” he says. “We’re asking for jobs. Think about how many jobs that RECLAIM can make for us.”

Patty Amburgey is secretary of the Black Lung Association chapter in Letcher County, now entering its fourth year. She turned to advocacy after her husband, Crawford, died of black lung in 2007, distraught that officials seemed unfazed about leaving desperate people and communities behind.

“It’s not only about the present, but also the future,” she explains. “That’s the reason I fool with this.”

Some of Appalachian minelands, and laid-off miners, are already part of smaller-scale, restoration pilot projects initiated by the Obama administration. That model resembles what a robust RECLAIM could be, but money for the pilots comes from a separate pot in the Treasury Department, not coal companies.

But those pilot projects don’t have nearly the heft of RECLAIM and its $1 billion.

“The McConnell piece remains crucial. If he makes this a priority, it passes,” says Eric Dixon, coordinator of policy and community engagement at the Appalachian Citizens’ Law Center.

“That RECLAIM money is our coal money and we want it back.”

-Patty Amburgey, Black Lung Association

As of press deadline in mid-December, McConnell and the Senate Republicans had taken a Band-Aid approach by including a one-year extension to the black lung excise tax in the initial draft of an end-of-year tax extender bill. Some GOP Tea Party members had threatened to vote against the bill if the black lung tax was included. The House GOP budget bill does not include the extension.

Willie Dodson, a field coordinator with the advocacy group Appalachian Voices, has harsh words about the apparent disconnect between McConnell and Appalachia.

“Supporting either of these measures would be admitting that the coal industry is culpable for dire environmental and public health problems, and ought to be held financially responsible for addressing them,” says Dodson, adding that McConnell’s allegiance is to the National Mining Association.

“Coal-state politicians talk a lot about how much they support coal, but that has never meant they support the miners or the folks who live where coal is mined.”

Voices for the future

The law center and other nonprofits, such as Kentuckians for the Commonwealth, have been instrumental in helping community members go beyond kitchen table griping sessions, Amburgey says. They have learned to set an example for the next generation by voicing their needs to those in power.

“That RECLAIM money shouldn’t lay there,” she says. “It is our coal money and we want it back. We have acres and acres of stripped land that can be straightened up and reused.”

When she needs motivation to push and prod local government leaders into backing the coalition, she reflects on heartbreaking moments with her dying husband.

When he begged her for air, she would place her hand on the oxygen tank dial—one that couldn’t be forced any higher because it was already at maximum flow.

“Not being able to breathe took away his freedom and dignity,” she says. “Each time I brought him to the hospital, a different part of him was left behind. It embarrassed him to depend on other people.”

Sanders is also frustrated by his limitations. And he resents being owed at least $70,000 in federal black lung compensation and benefits because of a seven-year dispute involving coal and insurance companies.

As a 17-year-old, a strapping Sanders left coal country behind, eager to forge his future in Illinois.

“I stayed gone 14 years,” he says about marrying in Chicago, having three children and working at a defense plant. Upon returning home, he found jobs at a series of mines. During his spare time each autumn, he would forage and sell enough ginseng to buy school clothes for his son and two daughters.

““Being away, I never could get satisfied. It’s the mountains. They never let go of you.”

“Communities have been calling for policies that invest more in mine cleanup and link it with economic development,” says Eric Dixon of the Appalachian Citizens’ Law Center.

The Abandoned Mine Lands (AML) Pilot Program, funded by the U.S. Treasury, is a start. Kentucky has received $80 million of that federal pie since its launch in 2016 to retrain workers, clean up mines and boost the economy.

Annual investments in such projects are an exciting boost, Dixon says, but “transitioning the regional economy will require hundreds of millions of dollars.”

That’s one of the reasons they’re pushing for Congress to free up $1 billion for similar projects by passing the RECLAIM Act. That money already exists in a separate pot funded by coal operators.

“East Kentucky’s greatest asset is our people,” Dixon says about locals willing to innovate. They “could benefit from financial support of just and sustainable, bottom-up development enterprises.”

Here are three of those endeavors, two in Kentucky and one in adjacent Virginia.

Project Intersection: From Mine to Industrial Park

Norton, Va., absorbed a double whammy over the last decade when coal jobs nosedived and the natural gas industry fled for riper options in the Marcellus Shale.

“It’s almost as if you go through a grief period as you come to understand this is the new normal,” says city manager Fred Ramey. “Then we had to pick ourselves up, dust off, and move forward.”

Those shifts prompted the city of Norton to pursue funding for Project Intersection, an ambitious initiative to transform a 200-acre old mining site within city limits into a manufacturing hub.

The entire site earned a top ranking from the state by being adjacent to two four-lane highways and having access to utility infrastructure.

“We can’t just say, ‘We need jobs,’” says Ramey, a Norton native. “We had to have places ready to show to potential businesses. Now we do.”

Norton is diversifying in other ways, too. The city has turned its historic downtown hotel into a call center. Its hiking and mountain biking trails and access to adjacent Jefferson National Forest are a magnet for the outdoorsy set. Norton was selected by readers as Blue Ridge Outdoors’ Top Adventure Town in 2017.

Other draws are Flag Rock Overlook and a winsome statue of the area’s very own Woodbooger (think Bigfoot).

“This is part of what government is supposed to do to help its citizens,” Ramey says.

Elk Now Roam On Mountaintop Leveled in Pursuit of Coal

David Ledford dares to think big. Enormously big: he is planning a 12,000-acre refuge on a mountain that had its top blown off in the quest for coal. He envisions thousands of visitors arriving by car, bus and recreational vehicle and paying an admission fee to be immersed in what he’s calling the Appalachian Wildlife Center.

“There’s nothing like this within 300 miles in any direction,” he says, steering his pickup truck to the site where he plans to break ground on an 80,000 square foot, $18-million center that will house a restaurant, gift shop, museum, artwork, classrooms, and a theater.

Ledford and his business partner, Frank Allen, received $12.5 million of Kentucky’s AML Pilot Program money in 2016 to transform a mine site between Harlan and Pineville into an economic engine. Allen, the fundraising part of the team, is seeking millions more from other sources.

“There’s a severe lack of capital in coal country,” says Ledford, who grew up in Eastern Tennessee. “This part of the world gets next to nothing.”

They purchased 500 acres and signed a long-term lease on 11,000 adjacent acres. The center has hired local police officers to serve as guards, who spend significant time on the remote property shooing away ATV operators and cleaning up needles and other paraphernalia drug users leave behind.

If the center opens in 2020, as planned, Ledford expects to employ 166 on-site scientists and other specialists within five years. An ambitious business plan predicts its proximity to Gatlinburg, Pigeon Forge, and Great Smoky Mountains National Park will help annual attendance grow to at least 868,000 and add more than 2,800 area jobs by 2025. The endeavor could inject hundreds of millions of dollars into the regional economy, research shows.

Ledford’s goal of a giant grassland, he says, is in keeping with the research he conducts on the landscapes that existed centuries ago when Daniel Boone and others were traversing the Cumberland Gap.

Ledford has deployed prescribed burns and herbicides to knock back non-native plants and allow native grasses, shrubs, and trees to prosper.

That mix is a perfect habitat for the elk transported from elsewhere in Kentucky. The state started reintroducing the long-gone species in the late 1990s. The refuge also will be a magnet for imperiled and migratory birds large and small, and for bears, bobcats and deer.

“We’re bringing this stuff back,” Ledford says. “That’s the story we’re going to tell here. That even in coal country in Appalachia, this happened.”

Earning Power: Laid-off Miners go from Coal to Utility Work in Their Own BackYard

In spring 2015, James Sloane’s world was falling apart. His father was dying. And he was on the verge of losing the family homestead after being laid off for the first time after 23 years in the coal industry.

Sloane, embarrassed about not having an income, listened to a co-worker’s advice about a retraining program for miners at the local community college. Today, the 46-year-old earns very good wages as a mechanic for the utility contractor, Five Star Electric.

“This was a lifesaver for me,” says Sloane.

Since 2013, Hazard Community and Technical College has helped 269 laid-off coal workers find similar utility jobs using funding from the Eastern Kentucky Concentrated Employment Program. A sister technical college in adjacent Leslie County will be expanding that retraining as a project funded by a $1.15 million grant from the AML Pilot Program. That college is in the midst of designing and building an electrical substation on abandoned mine lands that will be the centerpiece of the new program.

“We asked laid-off workers, ‘What are you looking for?’” says Keila Miller, who coordinates training at Hazard Community College. “The number-one request was a comparable wage and not to have to move away.”

That resonates with Sloane, a Knott County native who came home to the mines after he got out of the Army. Finding a new job meant the father of two could keep his home.

“When your parents and grandparents worked their hind end off for that land and then gave it to you,” says Sloane, pausing to catch his breath.

“To lose it and have some total stranger living there. Even thinking about that, that’s painful.”

Grants from the Solutions Journalism Network and the Society of Environmental Journalists provided partial funding for these articles.