Tackle the East’s most iconic trails in one breathtaking new route

Jennifer Pharr Davis holds a banner after the first completion of the Appalachian High Route. All photos courtesy of Pharr Davis

IF YOU HAVE HIKED ANYWHERE IN THE EAST, there’s a good chance you’ve seen either a white rectangle or white dot painted on trees along the way.

The two trail blazes are world-renowned. The white blaze marks the 2,190-mile Appalachian Trail (A.T.) from Georgia to Maine, and the white dot marks the 1,200-mile Mountains to Sea Trail (MST) across North Carolina from the Smokies to the Outer Banks. The two trails are the longest and most popular footpaths in the South, and they provide access to nearly all of the 6,000-foot peaks in the Appalachians.

Now, the two trails have been joined in an epic loop co-designed by Jennifer Pharr Davis, former A.T. speed record holder, author, and owner of Blue Ridge Hiking Company. Davis and High Peaks Trail Association co-founder Jake Blood have created the Appalachian High Route, which connects the A.T. and the MST in a 350-mile loop.

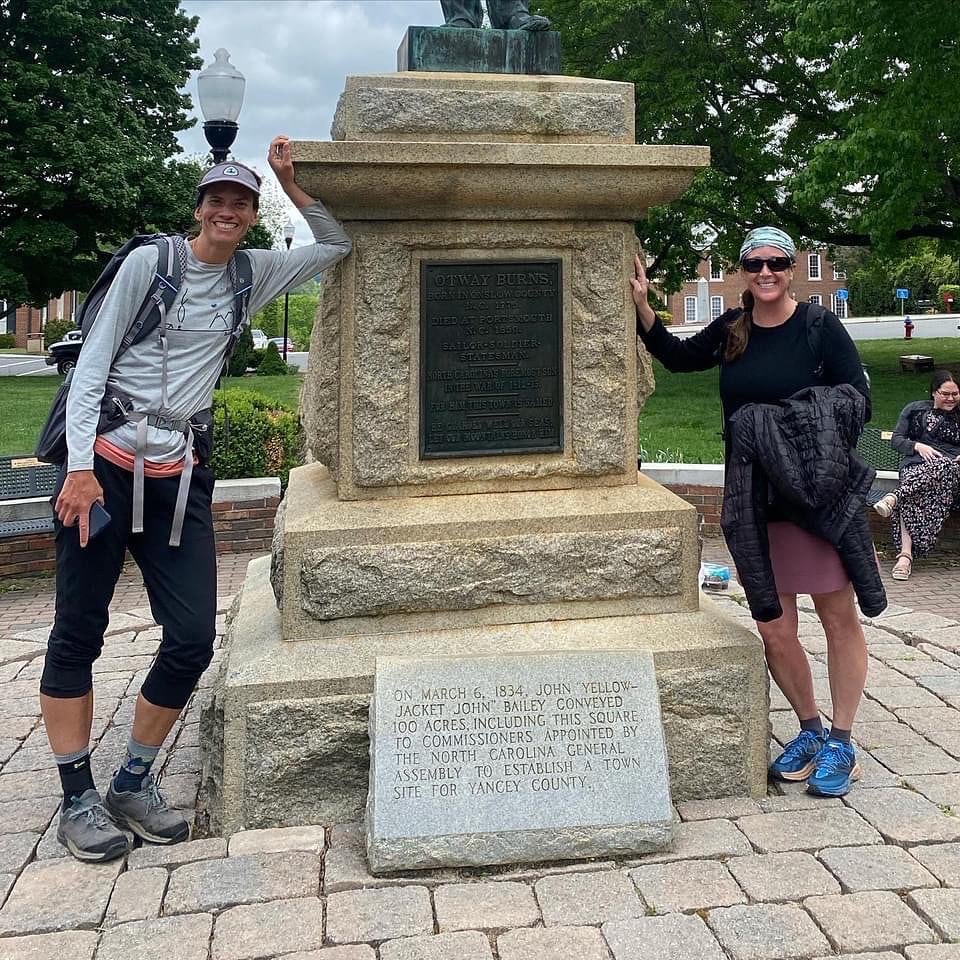

Co-creators: Jake Blood and Jennifer Pharr Davis at Bolens Creek

The Appalachian High Route includes the toughest sections of both trails, and it connects them using 19 scenic road miles and the Black Mountain Crest Trail, the most punishing 11 miles in Appalachia. The Black Mountain Crest Trail is also the highest trail in the East, with six 6,000-foot summits—including 6,684-foot Mount Mitchell, the highest peak east of the Mississippi.

“It’s really exciting to connect these trails and have community support for this new route,” says Pharr Davis.

The vision for the Appalachian High Route began on an Appalachian front porch, with Pharr Davis and Blood looking at maps and trying to connect these trails.

“I’ve always felt Mount Mitchell should have been a part of the Appalachian Trail,” says Blood. “After all, you hike over 2,000 miles and only go over the third-highest peak in the Appalachians [Clingmans Dome]. As the crow flies, Mount Mitchell is not even 20 miles from the A.T. On the ground, it’s a different story.”

Mount Mitchell is part of the Black Mountains, some of the steepest and most rugged terrain in the East. Finding a connective route wasn’t easy, but Blood was determined to connect Mitchell to the A.T., and working together with Pharr Davis, they created the Appalachian High Route.

The Appalachian High Route provides access to 50 of the 54 recognized peaks above 6,000 feet in the Appalachian Mountains. The route goes directly over many of these peaks, and the others can be accessed by side trails or bushwhacking. A 45-mile trail to the Appalachian High Route captures three of the remaining 6,000-footers. The only other 6,000+ foot peak in the Appalachians is Mount Washington in New Hampshire.

The Appalachian High Route also connects the highest peak in Great Smoky Mountains National Park (Clingmans Dome) with the highest peak in the East (Mount Mitchell). In doing so, this loop connects the story and history of the men who argued about the prominence of these mountains and for whom these peaks are named: Thomas Clingman and Elisha Mitchell.

In 1835, Mitchell used barometric observations to measure the height of the peaks of the Black Mountains, determining the highest one—the future Mount Mitchell—to be 6,672 feet. Senator Thomas Clingman, a former student of Mitchell’s, insisted another peak was the highest. Heated debates ensued, and Mitchell died while returning to verify his measurements. A U.S. Geological Survey in 1882 upheld Mitchell’s measurement of the highest peak and officially named it after him.

The Appalachian High Route fulfills the dream of the Appalachian Trail founder Benton MacKaye, who wanted to connect the highest peak in the north (Mount Washington) with the highest peak in the South (Mount Mitchell).

The linchpin in the Appalachian High Route is the newly established Burnsville Connector that provides a 19-mile road corridor connecting the trails. The Burnsville Connector road walk starts at the northern terminus of the Black Mountain Crest Trail and follows Bolens Creek into historic downtown Burnsville. The road walk then parallels Cane River to reach the Lost Cove Trail where it feeds into the Appalachian Trail.

The Burnsville Visitor Center serves as the unofficial headquarters and starting/ending point for the Appalachian High Route. Trail maps, patches, and an audio interpretive guide for the Burnsville Connector are in the works as future resources available at the Visitor Center.

Other trail towns along the route include Hot Springs, Asheville, and the Qualla Boundary of the Eastern Band of Cherokee.

Pharr Davis and Burnsville’s Haley Blevins became the first known finishers of the Appalachian High Route last month. Jake Blood, Burnsville Mayor Russell Fox, Burnsville-Yancey County Chamber of Commerce Director Christy Wood, and several local residents and supporters joined them for the final few miles.

First known finishers: Haley Blevins and Jennifer Pharr Davis

Pharr Davis has previously hiked the Appalachian Trail three separate times, and in 2011, she completed it in a record-setting 46 days. That’s an average of 47 miles per day.

As a mom of two young children, Jennifer has yet to slow down: she has covered 14,000 miles on six continents, written nine books, and founded Blue Ridge Hiking Company. She serves on the President’s Council on Sports, Fitness, and Nutrition, and has been recognized as a National Geographic Adventurer of the Year.

Appalachian High Route co-creator Jake Blood has helped protect and maintain over 1,200 miles of trails in Pisgah National Forest. He continues to serve as board member of the North Carolina High Peaks Trail Association and has served as board member of the Friends of the Mountains to Sea Trail.

If you have ever dreamed of hitting all of Appalachia’s highlights in one epic hike, this is your chance. This summer, tackle the highest, hardest hike in the East: bag 50 summits over 6,000 feet and become one of the first Appalachian High Route finishers.

An Appalachian High Route Community Information Session will be held August 4 at 6 p.m. at the Burnsville library. You can also learn more at blueridgehikingco.com.

Notes from the Final Miles of First Appalachian High Route Completion

By Jennifer Pharr Davis

Last month, I hiked the Burnsville Connector portion of the Appalachian High Route with my good friend, uber hiker, and Burnsville resident, Haley Blevins.

On the first day, I joined Jake Blood and his wife, Cynthia, on a hike into Lost Cove. We passed the rock foundations of old houses and barns, found abandoned cars and farm equipment, visited the cemetery, and found some amazing old-growth maple and poplar trees. We bushwhacked further to explore the abandoned settlement, and Cynthia found an unmarked grave in the woods.

From Lost Cove, I took the Devil’s Creek Trailhead to meet back up with the Forest Service Road and the A.T. Along the way, I found a garter snake, pink lady slippers, lily of the valley, and lots of dwarf crested iris.

On Saturday, Haley and I hiked 14 miles between the Forest Service road and downtown Burnsville. The road was rural and winding, and even with a narrow shoulder, it was easy to avoid the limited amount of cars on the road. The route was filled with old barns and small family-owned farms. It was extremely scenic for a road walk.

We stopped to take lots of pictures. At one point, we stepped off the road to snap a photo of an old wooden barn and a woman stopped to warn us that if we wandered much farther on the landowner’s property we might get shot at. Good to know! And it was an important reminder that private property and trespassing is a big deal here. From the beginning of this dream, we discussed how it is important to let local landowners know that we are not looking to take anyone’s land to create the route.

We followed the sidewalk past Mountain Heritage High School and into downtown. We also stopped at the historical marker for the gravesite of African American musician Lesley Riddle, who was born in Burnsville and whose influence on the Carter family helped shape country music.

Saturday night, I camped with my family in the rain beside Bolens Creek. My husband packed our camping gear and accidentally only packed one lightweight two-person tent for the four of us. We didn’t get a lot of sleep that night. I was more than ready to wake up and play at the old Ray Mine site with my kids, looking for quartz, garnets, mica, and kyanite.

At 1 pm, we left Bolens Creek and hiked three miles into Burnsville to complete the loop. Once again, the road was scenic and we didn’t have any trouble letting the post-church traffic pass by us.

As we hiked up to the Otway Burns statue in downtown, we played Chariots of Fire music and my kids cheered us on (because they knew that when we finished, they could eat cupcakes.) Haley says she tried to touch the statue the same time as me, but we have video evidence that she was faster and is the first known finisher of the Appalachian High Route. Regardless, we now have two finishers, and now the question is: how do we get more?

Cover photo: Jennifer Pharr Davis holds a banner after the first completion of the Appalachian High Route. All photos courtesy of Pharr Davis