Randy Moore—the first African-American Chief of the U.S. Forest Service in the agency’s 116-year history—faces unprecedented challenges. Here are five ways he can solve them.

“Forests are scary places for Black people,” says Kendra Thompson, a 34-year-old African-American woman who recently visited Pisgah National Forest for the first time. “Lynchings happened in forests. Bad shit went down.”

The forests still feel haunted to her and many African Americans, who have not always felt welcomed on public lands, especially in the South. Just last September, racist vandals hung a dead bear carcass at the entrance to Great Smoky Mountains National Park with a cardboard sign that read, “From here to the lake black lives don’t matter.”

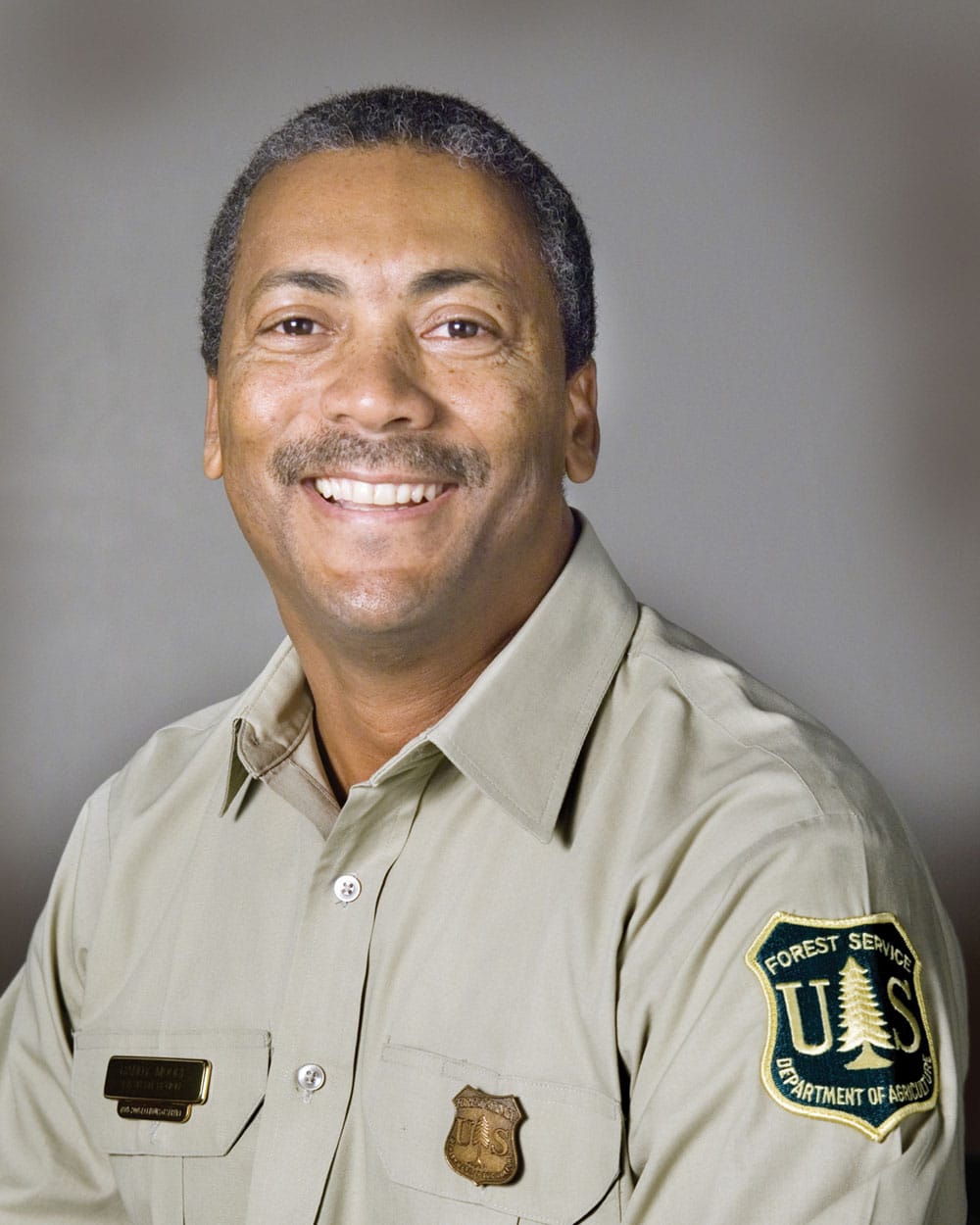

So it was an especially powerful and pivotal moment when Randy Moore was named the first African-American chief of the U.S. Forest Service last month.

The Forest Service was created in 1905 by Teddy Roosevelt, and he named Gifford Pinchot, manager of George Vanderbilt’s Biltmore Estate in Asheville, N.C., as the first chief. Sixteen white men and two women succeeded him. Now, for the first time in the Forest Service’s 116-year history, a Black man manages the country’s largest swath of public lands.

But Moore inherits an agency in crisis, and not just because of its racially charged history. Forests are more critical and controversial than ever. Wildfires are more severe and harder to control every year. Trump-era rollbacks of key environmental laws have left forests even more vulnerable, and climate change has made protecting forests even more urgent.

National forests cover roughly eight percent of all U.S. land. Most public lands in the Southeast are national forests, totaling over 8.1 million acres. When you look at a map, most of the green-shaded areas are national forests.

But national forests are also perhaps the least understood public lands. Unlike national parks, national forests can be logged and clearcut—and logging in national forests has been increasing in recent years. Mining, drilling, and fracked gas pipelines are also allowed on national forest lands. Yet most of the country’s old growth, rare species, scenic vistas, recreational opportunities, and drinking water supplies are found in national forests. One fifth of all drinking water flows from national forests.

Chief Moore now oversees 192 million acres of forests that are vital to the country’s health. With so much to do—and so much at stake—here are five issues that should be at the top of Chief Moore’s to-do list:

1. Store more carbon.

As a first priority, Chief Moore should set a science-based goal to store carbon across national forests to mitigate the impacts of wildfires and catastrophic climate change. Older, mature forests store significantly more carbon as they age. Too often, however, the Forest Service emphasizes short-term timber sales that exacerbate the climate crisis and increase wildfire risk.

While “thinning” is touted as a way to reduce wildfire risk, commercial logging often makes wildfires worse. Logging large, fire-resilient trees leaves the forest drier and more susceptible to fire. Prioritizing carbon sequestration in national forests can make our forests healthier, less flammable, and more resilient.

2. Protect our remaining old-growth forests.

Before industrial logging, about half of forests in the Eastern U.S. were in old-growth condition; now, less than one percent of old-growth forests remain in the Southeast, and nearly all of those forests are on public lands. Federal lands protect the most important reservoirs of ancient forests and biodiversity. The Forest Service continues to log these rare forests rather than protecting and restoring them. It’s time for a clear and consistent policy that identifies and protects existing old growth in national forests and allows more forests with old-growth characteristics to mature.

3. Right-size the road system.

The Forest Service currently maintains more than 370,000 miles of roads—that’s nearly eight times larger than the entire U.S. interstate system. The maintenance backlog on this road infrastructure is nearly $3.5 billion. Chief Moore should set a measurable annual target for reducing the Forest Service’s maintenance backlog, whether from additional funding, relocating problem roads, or closing unneeded roads.

Right-sizing the road system can ultimately provide more and better public access. By closing unneeded, unused roads and building ones that provide improved access, the Forest Service can avoid billions in maintenance, enhance water quality by preventing erosion, and avoid the road closures that come with neglect.

4. Promote accountability.

Prodded by timber targets, local officials sometimes choose harmful and controversial work, such as logging old growth rather than restoring native diversity. An emphasis on short-term commercial logging has cost taxpayers billions and worsened wildfires and the climate crisis. Timber sales can no longer serve as the Forest Service’s primary metric. Carbon storage, water quality, and community participation need to be equally valued by the Forest Service.

The Forest Service can fix this by changing how it measures success. The agency should scrap its timber targets and instead track progress on carbon storage, water quality, and community protection.

5. Restore respect for public knowledge and input.

Public input is the best backstop to make sure that local decisions are accomplishing good things for the forest. Unfortunately, Trump-era rollbacks have eliminated public comment and scientific review from many of its logging, mining, and pipeline projects. Logging projects up to 2,800 acres no longer require environmental analysis and public input. The Trump rules have essentially cut the public out of public lands.

Removing public and scientific input from Forest Service decision making has damaged trust. The Forest Service must recommit to listening to stakeholders, partners, and local communities. Chief Moore should also take steps to bring in new and diverse community voices, steps that could make the country’s forests more welcoming for Thompson and other visitors of color.

Chief Moore can reorient the Forest Service to live up to its motto of managing forests for “the greatest good, for the greatest number, in the long run.”

“There is a real mismatch between what the public expects and what the Forest Service has been doing,” says Sam Evans, leader of Southern Environmental Law Center’s National Forests and Parks Program. “Chief Moore can lead the agency toward a broader suite of goals that enhance the ecological integrity and long-term health of the forests. He also can bring in new voices that have historically been underrepresented. This is a moment of crisis for the Forest Service—and also a moment of opportunity.”

Cover photo: Moore became the new chief of the U.S. Forest service in late July. Photo courtesy of the U.S. Forest Service